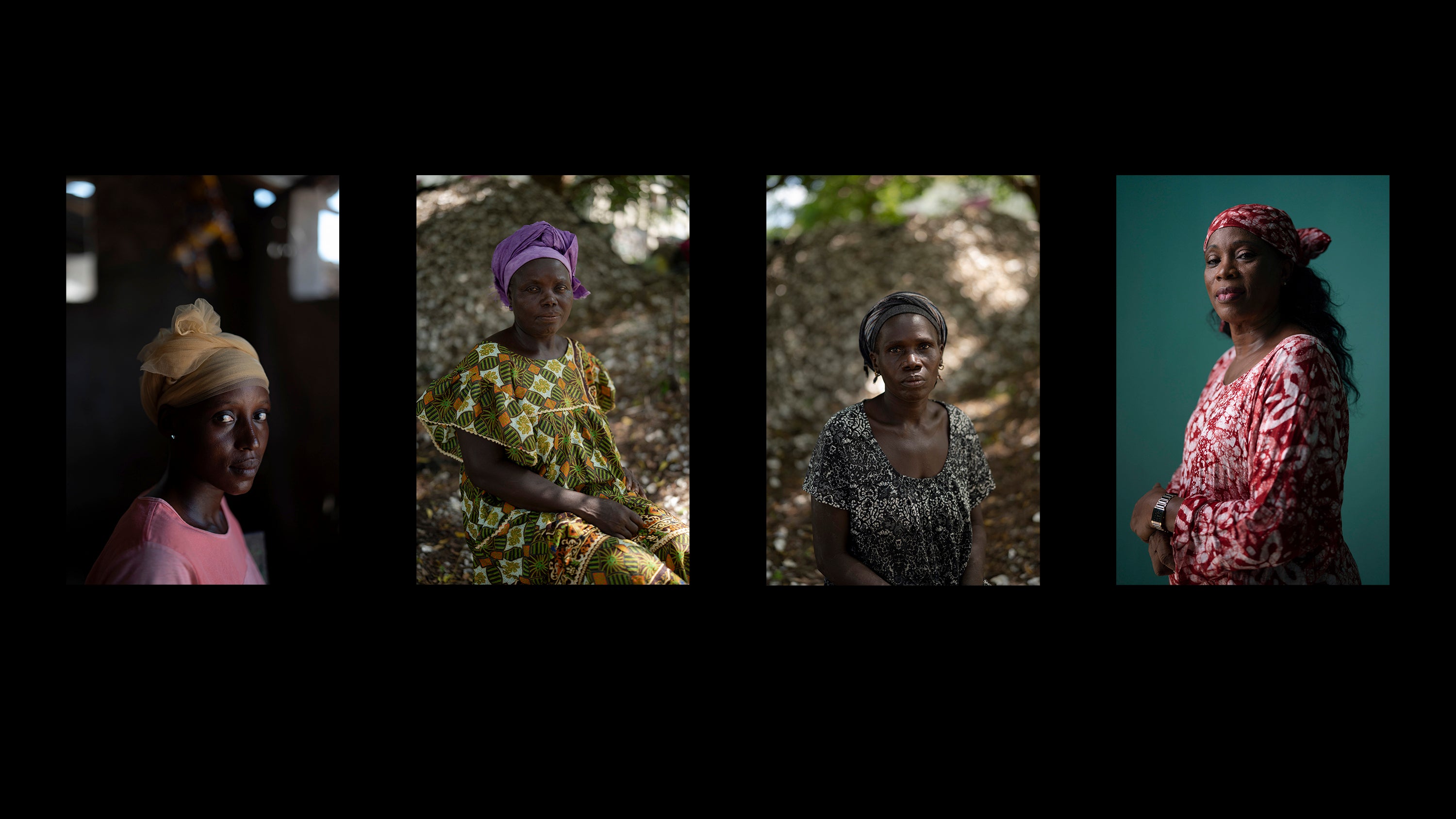

Gambian women's voices on COVID-19 vaccines: "We are afraid"

Oyster harvesting in Gambia is considered women’s work

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Oyster harvesting in Gambia is considered women’s work. It's a grueling task — they paddle rickety boats, then get into water up to their necks to lay nets. Many of the women are the sole family breadwinners, and that burden has only intensified with the pandemic's economic hardships.

Oysters bring income just two months a year — the rest of year, the nets catch crabs and small fish.

The TRY Oyster Women’s Association represents more than 500 women, many of whom are reluctant to get vaccinated against COVID-19. These women fish under darkness of night without fear but are anxious about the vaccine. They say they can’t miss a day of work if it means being sidelined — even briefly— because of side effects from the jab.

Here are their concerns, in their words.

___

OUMIE SAMBOU, 50, UNVACCINATED

Sambou’s husband is older and can no longer work. She alone makes money to feed their five children.

“Our life since the coronavirus arrived has been very difficult. No one had anything, and no one was able to work. If I do not wake up and go to work at the water, I will not have anything for my children.

“When COVID-19 broke out, we were told that no one should work. For us, if we sit at home without going to work, what do you expect us to give to feed our children? If your husband isn’t strong enough to work and you both sit at home, how will you survive this along with your children?

“I’m not convinced to accept the vaccine. My mind did not accept it; this is why I said I will not take the vaccine.”

___

FATOU JANHA MBOOB, 67, VACCINATED

Mboob, head of the TRY Oyster Women's Association, tries to educate members and her staff about COVID-19.

"Every time we had a meeting ... I would tell them about my friends and relatives who had died of COVID-19.

“I took (the vaccine) when it was being offered to the health workers who did not want to take it. So I went in. And then when I got it, I tried to convince my workers around me — my house helpers, my staff — to take it. It wasn’t easy for all of them. I mean, they just didn’t believe in taking that vaccine. So my condition was: You either take the vaccine or you cannot come to my house, to work, to the office. So through that, they took it reluctantly.”

___

LUCY JARJU, 53, UNVACCINATED

Jarju lost her husband a decade ago and is the sole provider for her family. Four of her seven children live at home, along with her daughter-in-law and three granddaughters.

"What if I get it and the vaccine does not work with my blood and brings me difficulties? I was told to go and take the vaccine, but I said that I was scared. If I take the vaccine and I can't move again, what will I do?

"I can’t deny the fact that it exists; it does exist. I’m only scared about the vaccine. It’s my only concern. The way I hear people talking about it, that’s why I’m scared."

___

MADELINE SAMBOU, 66, VACCINATED

Sambou, mother of three, was vaccinated after pressure from her grown children. Her peers haven't been persuaded by her experience.

"When I took the vaccine, it did not cause any problems. I went, took it and came back and I was able to cook my food, do the laundry, and all my activities.

"People were saying: ‘You are definitely strong. The injection vaccine did not cause any problems for you, you are doing your work.’"

___

SABEL JATTA, 60, CONSIDERING VACCINATION

Jatta, is a widow and mother of seven.

“We don’t have a husband. The river is our husband.

"I’m not scared of the virus. I’m scared of the vaccine.

"The vaccine they are giving abroad is better than the one they give here. The one given here is not good.

"I have seen my children that have taken the vaccine. Now it’s only me that has not taken it ... but I will go again.”

___

ROSE JATTA, 49, UNVACCINATED

Jatta suffers from chronic health issues but still goes out in search of food on the river daily. She fears the vaccine could make her sicker, leaving her two children without food.

“My kids only depend on me. Who will help my family if I cannot work?”

___

FATOU JATTA, 66, UNVACCINATED

Jatta, mother of three, has no plans to be vaccinated.

“We are afraid of the vaccine. Some people will take it and will have more problems in their bodies.

“I'm not taking it. My body can’t handle it.”

____

ANTA SAMBOU, 66, UNVACCINATED

Sambou, a mother of six, knows the virus exists but doesn't want the jab.

“We pray for the virus to leave and go back where it comes from. The river, the river is what we have."

___

This story is part of a yearlong series on how the pandemic is impacting women in Africa most acutely in the least developed countries. AP’s series is funded by the European Journalism Centre’s European Development Journalism Grants program, which is supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation AP is responsible for all content.