Paul Rudolph at 100: beyond the architect’s Brutalist reputation

As the movement comes back into vogue, Jason Farago looks at the design pioneer’s work

“If you wait long enough, what is admired will be relegated to history’s dustbin,” wrote Ada Louise Huxtable, “and if you wait even longer, it will be rescued and restored.”

That cycle has repeated more than once for Paul Rudolph (1918-1997), one of the most celebrated architects of the 1960s, whose reputation keeps oscillating between fame and neglect. His hulking Yale Art and Architecture Building in New Haven, Connecticut, completed in 1963, put Brutalism on the map in the United States; his houses, with boggling layouts, were the height of Johnson-era chic.

Then his star fell, and clients and critics dismissed his hard-edge slabs for postmodern wackiness. By this century, his buildings were most often in the news when facing the wrecking ball. But time is the best critic. Brutalism is back in vogue, and Rudolph, born a hundred years ago in October, is back in the matte lucite frame.

A pair of exhibitions now on view in Manhattan offers a lesson in the vagaries of architectural taste and a reintroduction to a master of solid and light. The show Paul Rudolph: The Personal Laboratory, until 30 December, concentrates on the architect’s residences, which is fitting given the location: the top floors of the Modulightor Building, a townhouse he built toward the end of his life on East 58th Street, which houses a light-fixtures firm he co-founded.

Downtown at the Centre for Architecture, the smaller exhibition Paul Rudolph: The Hong Kong Journey, until 9 March, looks at the architect’s work from the 1980s, when he found new opportunities in Asia.

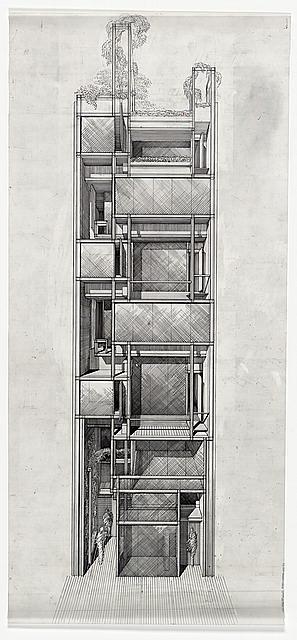

The Midtown show is especially illuminating. Rudolph made his name with residential architecture in Sarasota, Florida, and by the 1960s he had become the go-to builder for tony townhouses in Manhattan and the suburbs. If you only know Rudolph for his large-scale work, you might be surprised by these houses, which arrayed domestic life with a choreographer’s precision. Rudolph’s favorite trick was to use risers, stages, runways and pits to create dozens of interlocking spaces in a single interior. These fluid arrangements blurred private spaces into communal ones and mashed narrow passageways against vertiginous expanses.

Rudolph’s name has been synonymous for so long with Brutalism’s solidity that we forget how camp his architecture was

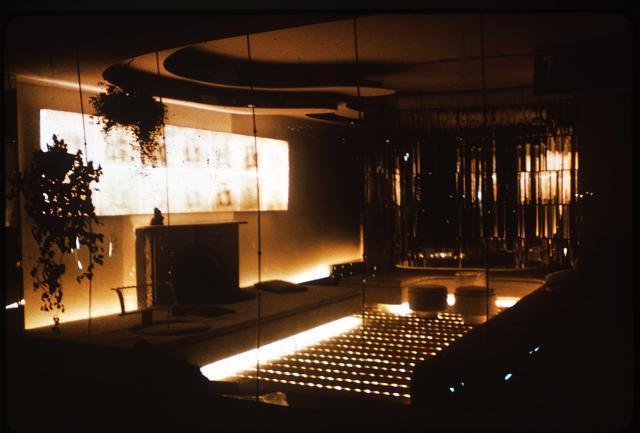

Rudolph employed these porous volumes best at his own home at 23 Beekman Place – New York’s ultimate party house. Cantilevered over the FDR Drive, the quadruplex apartment has few walls inside; instead, variable floor heights produce 27 interior levels that encourage visitors to preen and goggle. The surfaces are chrome, Formica, green plastic, white sheepskin. The thrusting terraces have views of Roosevelt Island and the Queensboro Bridge. Just as dramatic are the plunging views inside, from the apartment’s treacherous catwalks and banister-free floating staircases. (Pity the cleaner who nearly broke her neck wiping down the Plexiglas walkways.)

These spaces, and the multilevel interior of the Modulightor penthouse, provide a corrective to the view of Rudolph as a Brutalist heavyweight, a maker of buildings as severe as his military haircut.

That reputation derives largely from a few familiar early civic structures, above all the Yale building, which he designed after becoming the dean of the university’s architecture school. The structure’s bush-hammered concrete walls call to mind wide-wale beige corduroy – if corduroy could make you bleed when rubbing your hand across it – but it also had freer touches, like plush vermilion carpets and nautilus shells embedded in the walls. After a fire gutted the Yale building in 1969, it became, in Huxtable’s phrase, “possibly the period’s most conspicuously reviled modernist structure”. (The building, reopening in 2008 after a major renovation, has been renamed Rudolph Hall.)

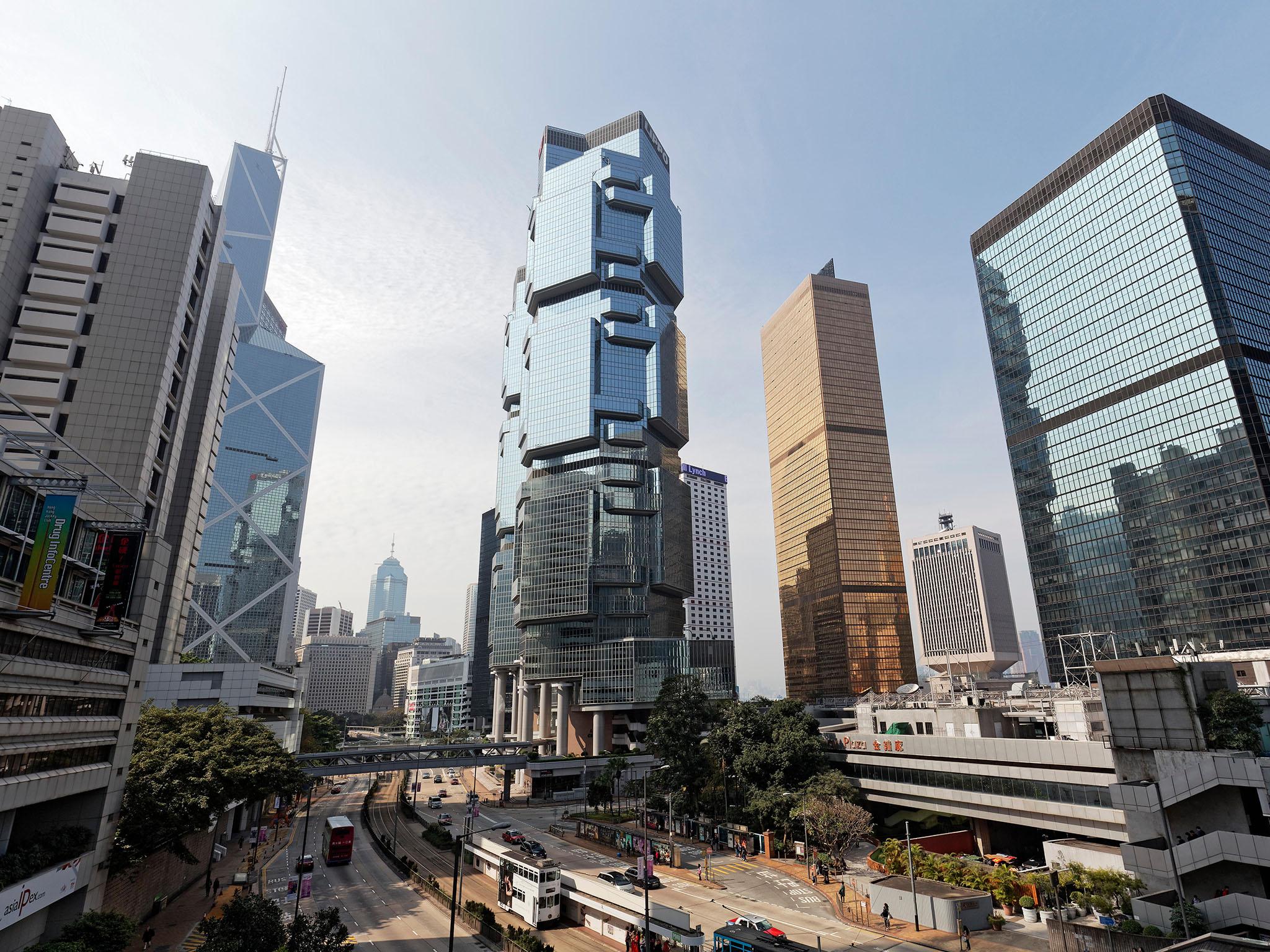

In his later years, the architect found a more receptive clientele in Singapore, Jakarta and Hong Kong – the latter being the focus of the current show at the Centre for Architecture. Rudolph’s Bond Centre in Hong Kong, now known as the Lippo Centre, makes use of prefab glass panels rather than concrete expanses, but its multilevel lobby breaks the towers’ mass into human-scale zones for meeting and mingling. (Hong Kong Island, with its dense urban fabric punctured by outdoor elevators and elevated passageways, must have seemed a paradise to him.) The show also includes an unbuilt house on Victoria Peak whose thrusting volumes of staggered boxes are less Brutalist than Bond villain.

Indeed Rudolph’s name has been synonymous for so long with Brutalism’s solidity that we forget how camp his architecture was. At Yale, Rudolph impaled Ionic capitals on dainty little pikes, like olives on cocktail skewers. The revelers inside the fashion designer Halston’s townhouse at 101 East 63rd Street, yours today for $24m (£18.6m), had to traverse one of Rudolph’s arch catwalks to reach the white leather couches fit for Studio 54. At Beekman Place, the shower had a clear glass floor affording a sotto-in-su titillation to the guest room below.

Rudolph’s architecture was solid and monumental on the outside, but behind closed doors it winked and ogled. He would surely be gratified by his return to prominence at age 100, but I suspect he would wonder at some of today’s Brutalist fanboys – the ones who slaver over Instagram views of past utopias and prefer their architecture crumbling and empty. Behind the thick concrete, his buildings were meant for lusting as well as looking, and make sense only when filled with bodies.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks