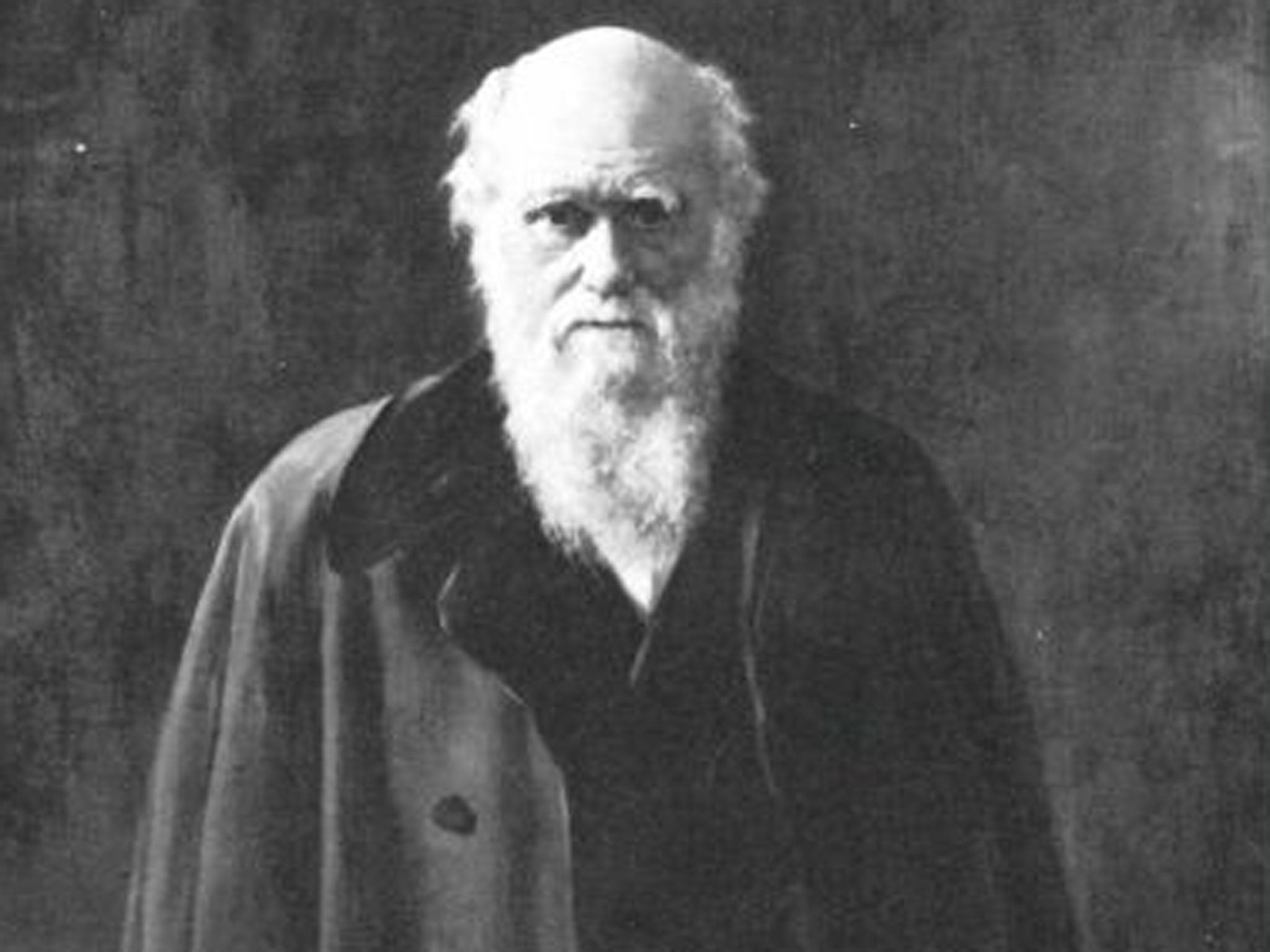

Page 3 Profile: Charles Darwin, father of evolution

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Surely we know everything we can about Darwin?

You’d have thought so, but newly released letters between the naturalist and Joseph Hooker – a botanist with whom he shared a 40-year friendship – have revealed yet more about both Darwin the scientist and Darwin the man. The Cambridge Digital Library has published almost all of their correspondence – 1,200 letters in total – on its website, though even the keenest Darwinian may have some trouble deciphering their handwriting.

How did they get to know each other?

Hooker was invited to work on plant samples collected from Darwin’s Beagle voyage to South America and the Galapagos. They began writing to each other in 1843, and by the start of 1844 Darwin trusted his contemporary enough to divulge his most precious scientific discoveries.

He told Hooker of the “gleams of light” that had led him to believe that species “are not immutable”, though he admitted that telling someone felt like “confessing a murder”. Darwin would later send him sections of the manuscript of On The Origin of Species, which was published in 1859. In another letter, he describes the Prussian explorer Alexander von Humboldt – chiefly recognised for his work in Latin America – as the “greatest scientific traveller who ever lived”.

How very humble!

He can be funny too. He advocated the use of chloroform during childbirth, claiming it would be “as composing to oneself as well as to the patient”. There are also plenty of touching, personal moments. Darwin wrote to Hooker straight after the death of his six-year-old daughter, Maria. “My darling little girl died here an hour ago and I think of you more in my grief than of any other friend.” As time goes by, the letters grow sadder. In 1881, the year before Darwin’s death, he claims his brain has “gone mud” on geographical distribution. Hooker tells Darwin of how many of his friends have died.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments