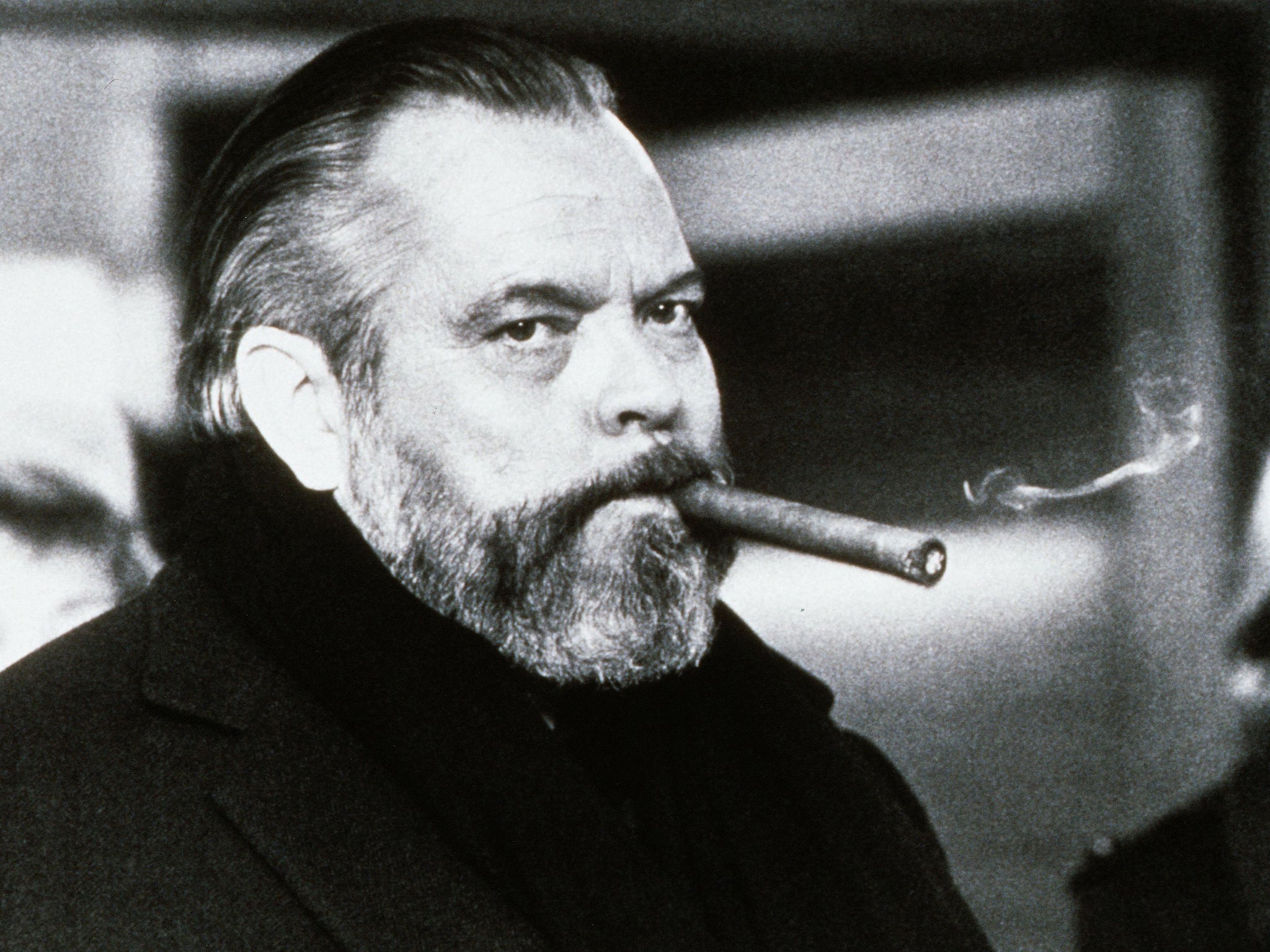

Orson Welles’ last film hits screens – 50 years after it was shot

Welles left 'The Other Side of the Wind' unfinished upon his death in 1985, with more than 100 hours of footage stored away in a Paris warehouse for decades. Now, the film is making its debut

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Orson Welles was on the phone. “What are you doing Thursday?” he asked.

It was 1970, and the Citizen Kane director had called filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich to ask him to appear in his latest film The Other Side of the Wind. Yes, he knew Bogdanovich was stretched thin. Just drop by the set on Thursday, Welles insisted. The whole movie was only going to take a few weeks to shoot – tops.

Forty-eight years later, The Other Side of the Wind has finally arrived. It was shown for the first time in the US at the Telluride Film Festival, where two new documentaries about the herculean efforts to finish the film were also screened. “It’s sad because Orson’s not here to see it,” Bogdanovich, 79, says from the stage of the Palm Theatre here. “Or maybe he is.”

Cinema buffs had almost given up on The Other Side of the Wind, which Welles left unfinished upon his death in 1985. It is known as one of the most famous movies never released, held up by warring rights-holders and never-ending financial troubles, including a failed funding effort by a relative of the former Shah of Iran.

No lesser a force than Frank Marshall, one of the most powerful producers in Hollywood, had been leading the salvage effort. Marshall, 71, made his name by making the impossible possible – shutting down the Las Vegas Strip to shoot Jason Bourne, staying calm when Steven Spielberg asked him to find 10,000 additional snakes for a scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark, figuring out how director Clint Eastwood could crash a jetliner for Sully. If he couldn’t pull the film over the finish line, who could?

Once the film’s producers finally secured firm funding – Netflix stepped up last year – they had to sort through more than 100 hours of footage (long stored in a Paris warehouse) to craft a film that Welles conceptualised as a type of collage, with some parts in colour and others in black and white, and scenes shot in various formats (35mm, 16mm and Super 8).

“No one really knew if we had enough material to put together a movie that actually made any sense,” Marshall says.

The masses will soon get to decide for themselves. The Other Side of the Wind will arrive on Netflix and in a handful of theatres on 2 November. So far, the critics at Telluride and the Venice Film Festival – where the film had its premiere on 31 August – have responded with unanimously positive reviews. The early reaction from festivalgoers has been mixed, with some befuddled and bored and others enraptured – just about typical for Welles, who specialised in polarising cinema.

The Other Side of the Wind reconstructs a debauched party (using footage supposedly shot by guests) held at the home of Jake Hannaford, a nonconformist film director, just before he dies. Scenes from the ageing Hannaford’s unfinished comeback movie – screened at the party – are interspersed. John Huston, who died in 1987, plays Hannaford as a misogynist, safari suit-wearing alcoholic. Bogdanovich stars as Brooks Otterlake, a young director coming to prominence. Oja Kodar, who co-wrote the screenplay with Welles, acts in the bizarre film-within-the-film.

The result is a politically incorrect fever-dream that involves dwarf sidekicks, Kodar in “redface” as an Indigenous American woman, at least one orgy, a drive-in theatre, 1970s-era views of women (disposable) and inclusion (nonexistent), the mutilation of a doll, a car crash, mannequins, an ice cube, lanterns, rifles and a giant phallus built with chicken wire and perched on a sand dune, among other imagery.

“It will be interesting to see how The Other Side of the Wind is received,” Ray Kelly, who runs the site Wellesnet.com, says. He was monitoring online reaction from his home in Massachusetts, following the Telluride screening. “Many of Welles’ finest works, including Touch of Evil and Chimes at Midnight, had their detractors when they were released. It took years before they were fully appreciated.”

The Telluride premiere was attended by a wide range of people – a 21-year-old college student, Jack Dorfman, who described himself as a Bogdanovich nut; John Bailey, cinematographer and president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; Brad Bird, the animation whiz behind Incredibles 2. Before the lights went down, the mood was upbeat, with people praising Netflix for coming to the financial rescue and Marshall, supporting himself with a cane, greeting friends in the aisles.

“I’ve been looking forward to seeing this film since I was 12 years old,” says Randy Haberkamp, 61, the motion picture academy’s managing director of preservation and foundation programmes. Haberkamp said that as a boy in Ohio he had seen a CBS special on Welles that mentioned The Other Side of the Wind. “I remember thinking, ‘I can’t wait until it comes out,’” he says.

Afterwards, however, the atmosphere was notably sombre. Marshall, who was the film’s original production manager, and Bogdanovich returned to the stage, along with American film historian Joseph McBride, who appears in The Other Side of the Wind as a gauche young critic. For a minute, it seemed as if emptiness had suddenly hit them: Now what? Their 48-year battle to get the film finished and seen was over.

“It’s sort of bittersweet,” Marshall says.

“It’s a sad movie, I think,” Bogdanovich says haltingly. “Not only Orson’s last movie. But it’s sort of like the end of everything. It comes across to me like the end of the world.”

McBride took issue with some of the early reviews, which he felt gave Huston and other leading cast members short shrift. “If there was any justice in the world, there would be a lot of Oscars for this film,” McBride says. Variety magazine awards editor, Kristopher Tapley outlined the Oscar possibilities, writing that voters could honour the film as a feat of editing. Bob Murawski, who won an Oscar in 2010 for editing The Hurt Locker, stitched together Welles’ footage, relying in part on notes he left behind.

Absent from the Telluride screening were Filip Jan Rymsza, a European producer who gave The Other Side of the Wind a hard push in 2014 by helping to win over two mercurial rights-holders, Beatrice Welles, the filmmaker’s daughter and sole heir, and Orson Welles’ longtime companion, Oja Kodar.

Rymsza was anchoring the Venice premiere, where he read statements from Beatrice Welles and Kodar, both of whom cited poor health for not attending the Venice or Telluride screenings.

Kodar thanked Rymsza, Marshall and Bogdanovich, saying they had done “a great job” and that she hoped to attend a screening of the film this autumn at the New York Film Festival, where at least one of the documentaries about making The Other Side of the Wind will also play. The two non-fiction films are They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead, directed by the Oscar-winning documentary-maker Morgan Neville; and A Final Cut for Orson: 40 Years in the Making, directed by Ryan Suffern.

Beatrice Welles also heaped praise on the salvage squad, adding: “Is this Orson Welles’ goodbye? Impossible! He left behind far too much. I hope with all my heart that this picture will be able to reopen people’s eyes and souls to his massive talent.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments