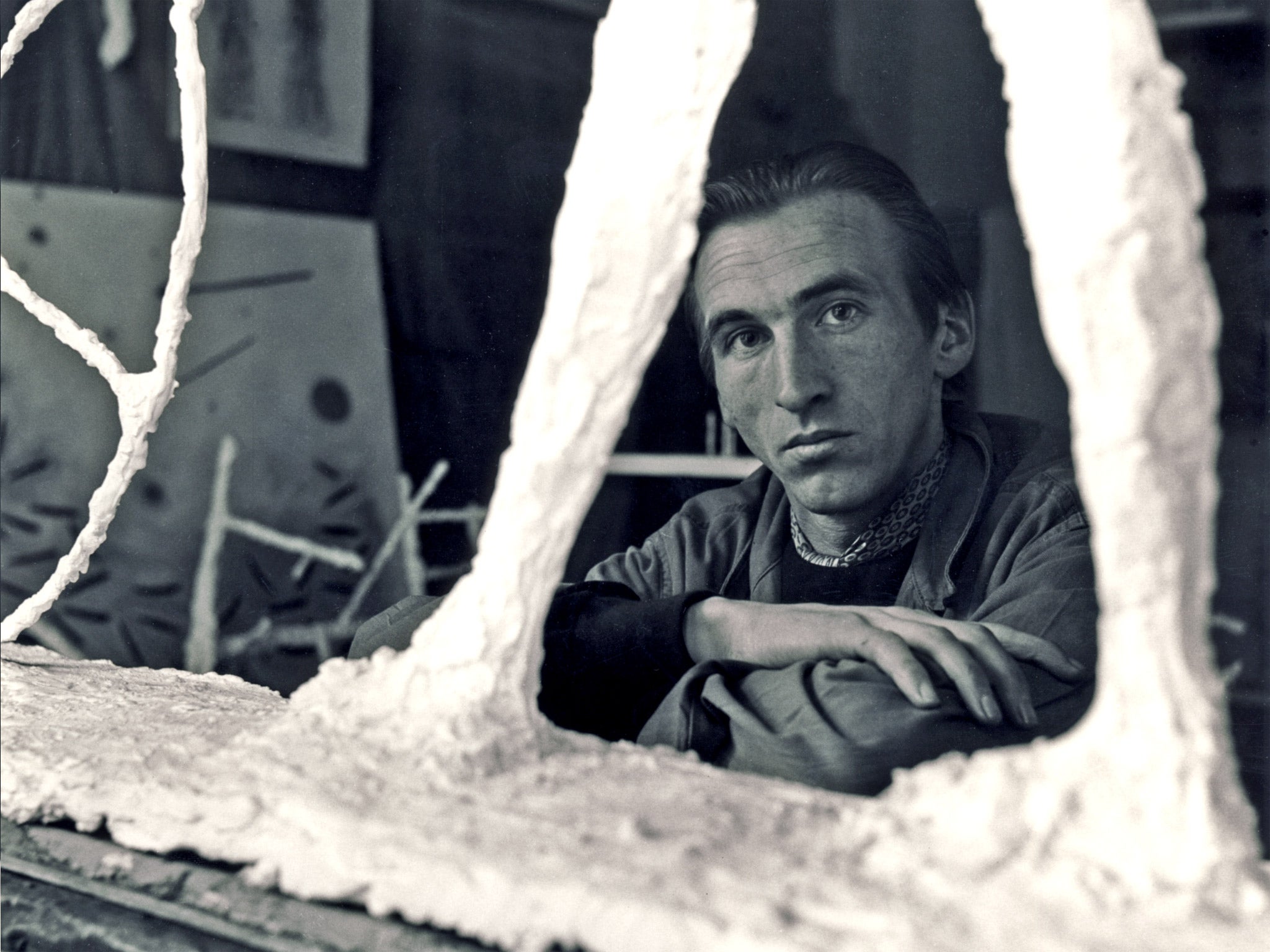

William Turnbull: One of the most highly regarded British sculptors of the 20th century

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Raised on stories of the First World War, William Turnbull avoided the army in the Second. "My thought was, 'How the hell do you get as far away from a trench as possible?'" Turnbull recalled, 72 years after joining up, from his native Dundee, at the age of 17. "Aeroplanes seemed a good idea."

His choice of the Royal Air Force in 1939 was to have far-reaching consequences. In the five years he spent as a pilot in the Far East, Turnbull saw life from a new vantage. "When you're looking down from an aeroplane, it's nothing like the kind of landscape Constable was painting," he remarked. "The dimensions were so peculiar, so different, they made you think of space as something else – almost as an object. It was endless abstraction, a totally different way of seeing the world."

The most obvious outcome of this new vision were the so-called "line paintings" Turnbull made in the late 1950. Hung on a wall, these have a literal feel – thin rivers of one colour winding through saturated fields of another. Their maker, though, was insistent that any resemblance between his images and the Earth as seen from the cockpit of a Mosquito was coincidental. "My paintings were objects, not illusions," he said, drily. This was reasonable enough. By the time Turnbull made works such as 05 – 1959, he had had another of the epiphanies that shaped his career. In 1956, the American banker and collector, Donald Blinken, had taken him to New York, and to the studios of the Abstract Expressionists.

It was not the first time Turnbull had fallen under the spell of foreign art. In 1948, after two years at the Slade – he quit the school's painting department for its sculpture studio in disgust at the prevailing Romanticism of the former – the ex-RAF pilot had gone to Paris on a serviceman's grant. With his first wife, the pianist Katharina Wolpe, he spent three cheerily penniless years living and working in a Montparnasse chambre de bonne.

The spidery aesthetic of the art Turnbull made at this time was partly a result of poverty – most of his sculptures were of plaster laid on cheap wire armatures – and partly of meeting Alberto Giacometti. Turnbull also introduced himself to the notoriously reclusive Constantin Brancusi, discovering the older man's address and turning up on his doorstep unannounced. After a dangerous pause, a stony-faced Brancusi had led the young Scot to his studio and left him there. Half an hour later his host came back, opened the door and growled, "You have to go now."

For all its brevity, the meeting was critical for Turnbull. If his sculpture of the early 1950s showed an exposure to Giacometti and Jean Dubuffet's art brut, the stacked works such as Magellan which he made throughout the 1960s were strongly Brancusian. Built up of elements of contrasting materials – wood, rough stone, polished bronze – balanced one on top of the other, these had the totemic feel of the Romanian master's. What they had no apparent relation to was Pop Art, although Turnbull's name was by now often linked to that movement.

Returning from Paris to London and even greater poverty – he made ends meet by working night shifts at an ice-cream factory – Turnbull had been introduced to the gallerist, Erica Brausen, by the critic, David Sylvester. In 1950 Brausen gave him his first show, at her gallery, the Hanover, alongside his fellow Slade student and Scot, Eduardo Paolozzi. Their success was immediate.

Two years later the pair showed again in New Aspects of British Sculpture at the Venice Biennale, one of the show's selectors, Herbert Read, coining the phrase "the Geometry of Fear" to describe the angst-ridden aesthetic of their work. Also in 1952, Turnbull and Paolozzi took part in the first meeting of the Independent Group at the Institute of Contemporary Arts. As the IG was to be most famous as the birthplace of British Pop Art – Paolozzi set the tone by feeding pages of American pulp magazines through an epidiascope – Turnbull found himself included in the movement willy-nilly.

This was largely a case of mistaken identity. If the works in his Idol series of the 1980s were inspired by film stars, and others made oblique reference to chocolate-vending machines, grandfather clocks and his sons' skateboards, Turnbull's interest in these things was always formal rather than populist. Four years after the IG meeting, in 1956, he and Paolozzi took part in the seminal sculpture exhibition This Is Tomorrow at the Whitechapel Art Gallery. This both set the seal on Turnbull's success and showed how very different his concerns were from Paolozzi's. As Richard Hamilton remarked in a film about Turnbull called Beyond Time, made by the sculptor's son in 2011, "Bill wasn't interested in all that mass media stuff. He was interested in Giacometti."

It may have been his unwillingness to sign up to any single group or school that led to Turnbull's being less of a household name than those of his fellow IG-ers. Arriving in New York in 1956, he visited the Abstract Expressionists in their studios: Rothko impressed him particularly, Turnbull's own canvases of the time showing a clear response to the American painter's deep saturations. When, in London, he had been lectured on his own art by the infamously controlling Clement Greenberg, though, he had refused to budge. As his friend Barnett Newman was to be in America, Turnbull was left off Greenberg's list of promising young British artists.

If he was bothered by this it did not show. Back home and by now married to the Singapore-born sculptor, Kim Lim, Turnbull took up teaching at the Central School and ploughing his own formal and material furrow. The 1960s and '70s found him experimenting with stainless steel and perspex, and – having travelled with Lim in the Far East – with totemic shapes seen at sites such as Angkor Wat. The last three decades saw a return to his first love, bronze. If his career never quite repeated the successes of the 1950s, it was none the less distinguished. A taste for Turnbull's work became a litmus test of taste among followers of modern British sculpture, Sir Nicholas Serota among them: there were shows at the Tate in 1973 and 2006. For all that, William Turnbull was, perhaps, too thoughtful for an artistic time given to shock and easy self-proclamation. "My work," he said, "is not ornate. It is the opposite, I suppose, of Baroque."

Charles Darwent

William Turnbull, artist: born Dundee 11 January 1922; married 1947 Katherina Wolpe (marriage dissolved), 1960 Kim Lim (died 1997; two sons); died London 15 November 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments