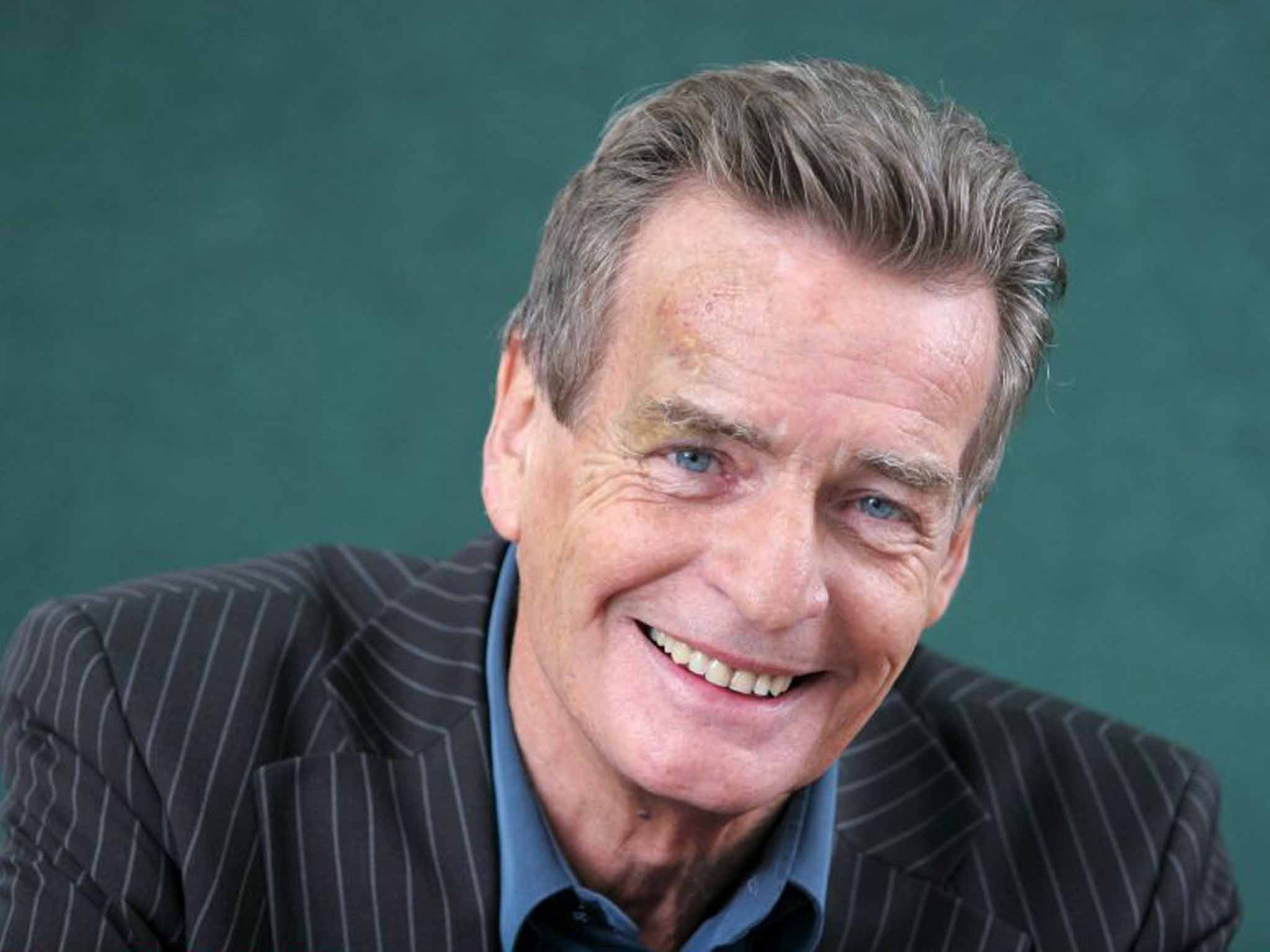

William McIlvanney: Author whose gritty Laidlaw novels began the 'Tartan Noir' genre, inspiring writers like Ian Rankin

A lifelong socialist and advocate of Scottish independence, he supported the Yes campaign leading up to last year's vote

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.William McIlvanney, who has died at the age of 79 after a short illness, was one of Scotland's finest writers and the godfather of “Tartan Noir”, that genre of gritty Caledonian crime-writing which made its first appearance in his 1977 novel, Laidlaw, whose eponymous detective hero investigates the sex-related killing of a Glaswegian teenager.

McIlvanney was born in 1936 in Kilmarnock, the fourth child of a former miner who had taken part in the General Strike 10 years beforehand. He studied at Kilmarnock Academy, where he became editor of Goldberry, the school magazine, and at the University of Glasgow, from which he graduated with an MA in 1960. Although he was the first of his family to go to university, he found himself disappointed with academic life, recalling that, “With some very honourable exceptions, I couldn't accept the mechanistic shallowness of much that was on offer”.

Following university, he worked for 15 years as a teacher at Irvine Royal Academy and then Greenwood Academy, Dreghorn. He published his debut novel, Remedy is None, in 1966, the story of a young university student from Graithnock (a thinly veiled Kilmarnock) whose father dies of cancer. With echoes of Hamlet, Camus' Outsider and of the author's own life – McIlvanney's father died of cancer while he was at university – Remedy is None was not a bestseller but it did win the Geoffrey Faber Memorial prize the following year, bringing him early recognition. The book was republished last year following a resurgence of interest in his early work.

Interviewed this year at the Glasgow Film Festival, he spoke of his good fortune, despite initially being turned down. “I've been very lucky in my attempts to write,” he said. “I wrote the first book, Remedy Is None, and you're obviously terrified. And it was rejected. Then someone said there's a thing called an agent and I got an agent... I was still teaching at the time...”

His third novel was Docherty, published in 1975 and set in a mining community, reflecting his family's history. “To me, Docherty is an expression of a whole stretch of working-class life.” McIlvanney told an interviewer earlier this year. The book won the Whitbread Prize for Fiction, prompting him to leave his job as assistant head teacher at Dreghorn to concentrate on writing.

Laidlaw, published in 1977, was the first of the “Tartan Noir” genre and went on to inspire other writers, including Ian Rankin and his series of Rebus novels. In Laidlaw we see the perpetrators of crime depicted as certainly flawed but essentially human; McIlvanney believed firmly that “there are no monsters... there's only people”.

When some suggested that McIlvanney might have gone downmarket in writing crime fiction after the acclaim accorded to Docherty, he responded that Laidlaw was “not a whodunnit but a whydunnit”. He emphasised that his books were not only about crime but were concerned with society as a whole. “He's a kind of figurehead for that time and that place,” McIlvanney noted, “and Laidlaw is not just an inspector of crime; he's an inspector of society. He's commenting on where we are and the problems of where we are and the aspects of where we are. I didn't set out to write a detective novel.”

The eponymous detective is depicted by his creator as “drinking too much – not for pleasure, just sipping it systematically, like low-proof hemlock. His marriage was a maze nobody had ever mapped, an infinity of habit and hurt and betrayal.” But it is not alcohol he keeps locked away: we learn that it is the works of Kierkegaard, Camus and Unamuno that the fictional detective hides in his desk. His Laidlaw trilogy developed through The Papers of Tony Veitch (1983) and Strange Loyalties (1991).

The Big Man (1985) was later adapted into the feature film of the same name, directed by David Leland and starring Liam Neeson as the unemployed miner who becomes a bare-knuckle boxer. McIlvanney also wrote three notable collections of poetry: The Longships in Harbour: Poems (1970), which includes the long poem “Initiation”, which deals with his father's death; These Words – Weddings and After (1984); and In Through The Head (1988). McIlVanney was a long-standing advocate of verse for the people, and in his essay “The Sacred Wood Revisited” he took on TS Eliot and what he saw as poetry's elitism.

Writing runs in the McIlvanney family. William's brother Hugh is an award-winning sports journalist whose trenchant prose has graced the Sunday Times for more than 20 years and The Observer before that. His son, Liam McIlvanney, is also a crime writer, best known for his prize-winning second novel, Where the Dead Men Go, set on the mean streets of Glasgow. His daughter Siobhan is a university lecturer.

McIlvanney, a lifelong socialist and advocate of Scottish independence, was disappointed by the outcome of the 1979 devolution referendum and had supported the Yes campaign leading up to last year's vote. Scotland's First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, paid tribute to him. “His writing – particularly Docherty – had a huge influence on me when I was growing up,” she said. “He came from the same part of Scotland as me – Ayrshire – and had taught at my school, so he was also something of a local hero. It was a big thrill for me years later to get to meet him. One of the last times I spoke to him was in the run-up to the referendum and he was full of enthusiasm about the prospects of a Yes vote.”

William McIlvanney, writer and teacher: born Kilmarnock 25 November 1936; married (marriage dissolved; one daughter, one son); partner to Siobhan Lynch; died 5 December 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments