Wayne Collett: Athlete who staged a Black Power protest at the 1972 Olympic Games

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

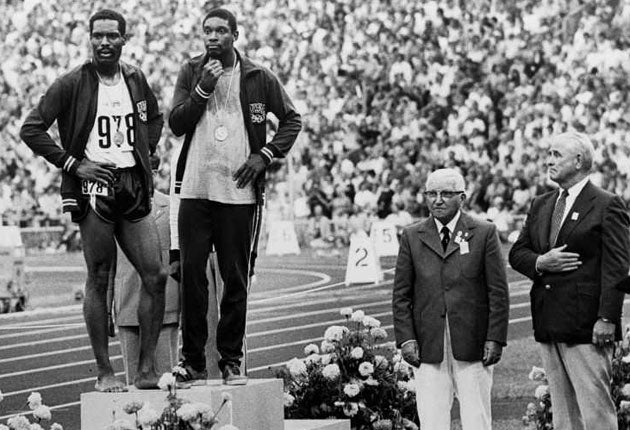

Your support makes all the difference.After receiving his silver medal for second place in the 400 metres at the 1972 Munich Olympics, Wayne Collett stood on the podium alongside the gold medallist Vince Matthews.

They turned away from the American flag, and with hands on hips, chatted casually until The Star Spangled Banner had finished. Then, as Matthews twirled his medal, Collett gave a black-power salute.

It was a far less dramatic protest than the famed bowed-head clenched fist demonstration by Tommie Smith and John Carlos in Mexico City four years before, but the official response was even more emphatic. In Mexico, the United States Olympic Committee had refused to expel Smith and Carlos from the games until the IOC threatened to disqualify the entire US athletics team. This time, when the IOC President Avery Brundage, who as head of the USOC in 1936 Berlin had authorised Americans to give the Nazi salute, called Matthews and Collett's actions a "disgusting display", the US team immediately sent them home. In their absence, and an injury to John Smith, the US withdrew from the 4x400m relay and Great Britain took the silver medal behind Kenya.

If Collett's political theatre failed to make the impact of Smith's and Carlos's, it was also far overshadowed by the tragedy of the kidnapped Israeli Olympians that cast a shadow over the Munich Games. It had an improvised quality. "I couldn't stand there and sing the words because I don't believe they're true," Collett said. On the 20th anniversary of Munich, he explained further, saying, "I love America. I just don't think it's lived up to its promise. I'm not anti-American at all. To suggest otherwise is to not understand the struggles of blacks in America at the time."

Collett had gone to Munich a heavy favourite after winning the US Olympic trials with the fastest 400m time recorded at sea level, 44.1 seconds, beating a field that included Lee Evans, whose world record had been set in Mexico's altitude four years earlier. Collett, and Smith, his college team-mate at UCLA, expected to finish one-two, but Smith pulled up hurt in the final, and Matthews was the surprise winner in 44.66, with Collett second in 44.80.

Born in Los Angeles, Collett was a high school track star who stayed at home to attend UCLA. Built powerfully at 6ft 2in and 180lb, he was dominant in the collegiate 440 yard race, and ran the anchor leg on three consecutive national championship 4x440 relay teams. His coach, Frank Bush, called him the greatest athlete he had ever coached. In 1972 he had supported Collett, saying, "I was disappointed and told him that to his face, but I love him just as much as I did before the Olympics."

After Munich, Collett returned to UCLA, where he had already earned his BA, and took business and law degrees. "People say that Mark Spitz's gold medals are worth $5 million to him," he said at the time. "One of my professors told me what I did cost me $100,000. Maybe it did, but my peace of mind, being able to sleep at night, being able to live with myself, is worth that much." He went on to practise law in Los Angeles before moving into real estate and mortgage brokering.

Collett died after a long battle with cancer, and is survived by his wife Emily and two sons, Aaron and Wayne II. On the 40th anniversary of Munich, he was asked if, knowing what he does now, he would have taken the same action. "Things are very different today," he said, "but I've never been one to sing the anthem. It's not my style."

Wayne Curtis Collett, athlete, lawyer, businessman: born Los Angeles 20 October 1949; married (two sons); died Los Angeles 17 March 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments