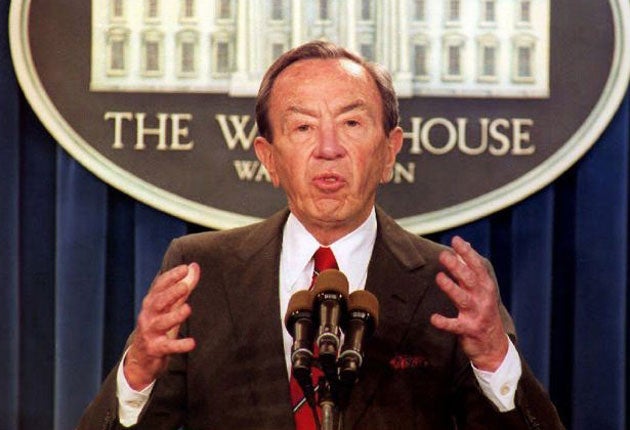

Warren Christopher: Lawyer and diplomat who served as Secretary of State under President Clinton

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There have been many greater American Secretaries of State. But if diligence, modesty, civility and concern for his staff were the sole requirements for the job he held for four years under President Bill Clinton, Warren Christopher would be without peer.

To describe him as buttoned-down would be an understatement. Weathered and lined like a prune in later years, his face was almost always expressionless – except perhaps when indulging a lifelong passion for Californian college basketball. His style was phlegmatic, courteous and endlessly patient. With the elegantly cut suits and brightly coloured ties that were his one concession to stylishness, he looked like a very expensive, very discreet and very wise lawyer – which is exactly what he was as well.

For more than four decades, Christopher alternated between the top-notch LA law firm of O'Melveny & Myers and the upper reaches of Democratic administrations in Washington, culminating in his tenure as America's 63rd Secretary of State. By then he was undisputed elder statesman of the Democratic party – a man presidents and candidates would turn to for particularly delicate tasks – and a leading light in the firmament of America's great and good. If there was a sensitive, high-profile public commission to be chaired, then "Chris", as he was widely known, was your man, as safe a pair of hands as could be imagined.

Los Angeles might have been his professional base, but Christopher's real roots lay 1,500 miles to the north-east on the empty plains of North Dakota, where he was born in 1925, the son of a small town bank manager. His reserved, self-effacing manner reflected his Norwegian immigrant ancestry and the austere Lutheranism with which he grew up. But his life changed for ever in 1937, when his father had a massive stroke brought about by the collapse of the bank.

In a vain attempt to restore his health, the family moved to Los Angeles. California would make Warren Christopher rich, successful and ultimately famous. But he never forgot the pain and and hardship of those Depression years. To them may be traced his lifelong concern for the underdog, his deep liberal instincts and his lifelong involvement with the Democratic Party.

The law, however, was his chosen field, and one in which he excelled. At Stanford he became the first editor of the university's Law Review, before heading to Washington, where he spent two years as a clerk for the great liberal Supreme Court Justice, William Douglas. Then he returned to Los Angeles where he joined O'Melveny & Myers, and made such an impact that he was selected to head the commission set up by the city to investigate the 1965 Watts race riots.

Largely on the strength of that exercise, he was summoned to government for the first time, as deputy attorney general for the final 18 months of the Johnson administration. As such, he helped shepherd LBJ's last piece of major civil rights legislation through Congress in 1968. A quarter of a century later, in 1992, Christopher was called upon to defuse another LA race crisis, this one stemming from the police beating of the black motorist Rodney King. Belying his non-confrontational reputation, he demanded – and secured – the departure of the LAPD's controversial chief Daryl Gates.

When the Democrats returned to power in 1977, Christopher was an obvious candidate for a senior job. In the event, President Jimmy Carter named him deputy Secretary of State, and Christopher's lawyerly, impeccably mannered way of diplomacy soon emerged. Up to a point it worked, most notably in the painstaking negotiations he led to secure the release of the US hostages in Tehran, a deal consummated only on 20 January 1981, the day Ronald Reagan took office.

In the process however, he gained a reputation he would never shake off, of lacking steel and ruthlessness when the crunch came. As Zbigniew Brzezinski, Carter's national security adviser, once wrote, Christopher was inclined "to litigate issues endlessly, to shy away from the inevitable ingredient of force in dealing with international realities ... with an excessive faith that all issues can be resolved by compromise." That judgement was indirectly confirmed by his wife Marie. In 35 years of marriage, she once said, the couple had never had a fight.

Critics pointed to similar defects a dozen years later when he was named by Clinton to the top State Department job. The appointment was a foregone conclusion once Christopher the party elder was chosen to head the transition team for the young incoming president. It was, alas, far from an unequivocal success.

The problem was not so much that the dour North Dakotan was a poor salesman of policy; rather that he had little of distinction to sell. Though Christopher devoted time and energy to the Middle East, the great achievement of Clinton's first term – the historic September 1993 handshake on the White House lawn between Yasser Arafat and Yitzhak Rabin – was mostly the fruit of Norway's labours, not his own. Policy for Nato and Russia was handled by his deputy Strobe Talbott. The Europeans blamed him for feebleness on Bosnia (and the 1995 Dayton accords which ended that war were hammered out by Richard Holbrooke). Failure to react to – even to acknowledge – the Rwandan genocide of 1994 was another lasting blot on the reputation of the Clinton team, and of Christopher himself. Rumours regularly surfaced that he was about to resign or be replaced, but in the event he served the entire first Clinton term.

On leaving government, he returned to Los Angeles and O'Melveny & Myers, but as usual remained active in Democratic politics. As usual, too, awards and civil distinctions were showered upon him. His last great test came when Al Gore chose him to supervise the battle over the Florida vote recount after the deadlocked 2000 Presidential election. Once again, Christopher performed with wisdom, decency and restraint. But on this occasion as well it was whispered that he was "too nice", allowing himself to be outmuscled by his wily, combative and less scrupulous Republican opposite number (and predecessor as Secretary of State) James Baker.

Warren Minor Christopher, government official and lawyer: born Scranton, North Dakota 27 October 1925; Partner, O'Melveny & Myers LLP (Los Angeles) 1958-1967, 1969-1977, chairman 1982-1992; Deputy US Attorney General 1967-1979; Deputy Secretary of State 1977-1981; Secretary of State 1993-1997; married 1956 Marie Wyllis (two sons, two daughters); died Los Angeles 18 March 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments