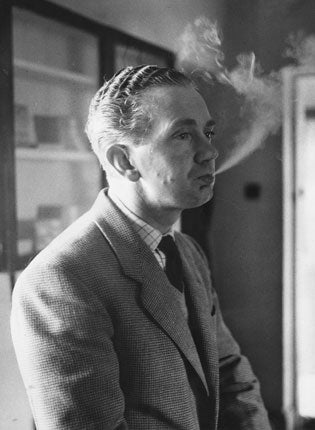

Vincent O'Brien: Horse racing trainer who enjoyed outstanding success in both National Hunt and Flat racing

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

No man has dominated horse racing to the extent of the Irish trainer Vincent O'Brien, a hero in his own country and one of the few people in sport who could accurately be described as a legend. From humble origins O'Brien achieved unsurpassed success in horse racing. He dominated both National Hunt and Flat, winning the Derby six times, the Cheltenham Gold Cup four, as well as three Champion Hurdles and an astonishing three consecutive Grand Nationals with different horses.

Since his first winner in 1943, horse racing has changed utterly, from a sport to a multi-million pound industry. O'Brien, the son of a County Cork farmer and small-time trainer, did not just move with the changes, he was at the forefront of them, nowhere more so than with his involvement with the owner Robert Sangster. In the late 1970s and early '80s they paid millions of dollars for the progeny of the stallion Northern Dancer and his sons, syndicating the successful ones for as high as $40m. Their partnership and subsequent rivalry with the Maktoum brothers of Dubai transformed the bloodstock world.

Born in April 1917, he was the eldest of four children from his father Dan's second marriage. He grew up around horses and could recite the pedigrees of his father's horses when still small enough to sit on his lap. His passion for thoroughbreds meant that O'Brien, regarded as an intelligent but recalcitrant pupil, left school aged 15.

Before his father's death in 1943, O'Brien had acted as his assistant, having a major input into the running of the yard. In line with Irish tradition, the farm at Churchtown was left to the oldest son of Dan O'Brien's first marriage, and for a while Vincent considered a career as a butcher. Eventually agreement was reached for him to rent the stables on the farm.

A few months after his father's death O'Brien bought a horse called Drybob for 130 guineas at the Newmarket December sales. Drybob, along with the four-year-old Good Days, may not rank with O'Brien's greatest horses, but they completed the 1944 Irish Autumn Double, the Cambridgeshire and Cesarewitch, landing huge gambles. The horses' owner Frank Vickerman won £Ir5,000 for £Ir10 each way; O'Brien collected £Ir1,000 for a £Ir4 stake.

By the end of his career, O'Brien had no need for gambles. But in the infancy of his career betting was no side-event; it was a lifeline. O'Brien gambles were meticulously planned and executed; the trainer kept a record of his bets in a neat ledger. Often he would pay for petrol or other commodities by placing bets for shopkeepers. Even the parish priest was in on the gambles in return for blessing the horses.

Vickerman, an English wool merchant, used his Drybob/Good Days winnings shrewdly, buying the gelding Cottage Rake, who signalled the advent of a remarkable era: Vincent O'Brien at the Cheltenham Festival. In 12 years, he saddled 23 winners there. Cottage Rake started at 10-1 when he won the 1948 Cheltenham Gold Cup, jumping brilliantly despite inexper-ience. Only months earlier he had won the Irish Cesarewitch on the Flat, and that was a typical trait of O'Brien-trained National Hunt horses: impressive finishing speed which enabled them to quicken away from equally talented jumpers racing up the steep Cheltenham finishing straight.

The following year O'Brien was back at Cheltenham to see Cottage Rake win the second of three consecutive Gold Cups and Hatton's Grace land the first of a hat-trick of wins in the Champion Hurdle. O'Brien also trained Knock Hard to win the 1953 Gold Cup. These two demonstrated the versatility of O'Brien's horses: both had enough speed to win the Irish Lincolnshire over a mile on the Flat.

O'Brien's achievements in the Grand National are peerless. He nearly won with his first runner; in 1951, Royal Tan, partnered by O'Brien's younger brother Phonsie, jumped the last alongside Nickel Tan before a blunder cost him the race. The following year Royal Tan again looked the winner but fell at the last. His turn came in 1954, a year after O'Brien had taken the first of three consecutive Nationals, with Early Mist. Quare Times, one of four O'Brien runners in 1955, was the only one to appreciate the heavy going and won by 12 lengths from Tudor Line. Quare Times had been bought for 300 guineas as a yearling but was not put into training until he was seven, an indication of his O'Brien's extreme patience.

Inevitably, any career, no matter how brilliant, will suffer setbacks, and in 1954 O'Brien lost his licence for three months over what the Irish Turf Club stewards described as "discrepancies in the English and Irish form of four horses, Royal Tan, Lucky Dome, Early Mist, and Knock Hard." The decision provoked outrage in Ireland and even prompted criticism in the Dail Eireann, one member, Mick Davern, referring to "green-eyed individuals" being behind the decision.

In 1951, the same year he met his Australian-born wife Jacqueline Wittenom, the daughter of a politician, O'Brien moved from his Churchtown stables to Ballydoyle in County Tipperary. He developed Ballydoyle into one of the most impressive training complexes in the world, his gallops including a downhill, left-handed bank like Epsom's Tattenham Corner. This unique gallop has been used extensively by O'Brien's long-term successor at Ballydoyle, Aidan O'Brien (no relation) who will saddle an amazing six of the 13 runners in Saturday's Derby.

Eight years after the move, O'Brien announced he was to concentrate on Flat horses. By that time he had proved his skills were equally suited to the Flat. Two of the best early O'Brien-trained Flat horses ware Ballymoss and Gladness, both owned by John McShain, an American on the look-out for a European trainer when he met O'Brien at the 1955 Doncaster yearling sales. There they bought Ballymoss, who finished second to Crepello in the 1957 Derby and subsequently won the Irish Derby, English St Leger, and, as a four-year-old, the Coronation Cup, Eclipse, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, and the Prix de l'Arc de Triomphe. In 1956, the mare Gladness won the Ascot Gold Cup, Goodwood Cup, and the Ebor Handicap.

Two years later O'Brien was banned from training and had to leave Ballydoyle with his family for a year when his horse Chamour gave a positive test after winning the Ballysax Plate at The Curragh in April 1960. Samples of sweat and saliva were found to contain 1/10,000th grain of an amphetamine derivative called methylamphetamine.

Although his ban was reduced from 18 months to a year, O'Brien was outraged and fought hard to have the decision reversed, with the backing of a number of international laboratories. The Irish Turf Club provided no evidence that O'Brien had administered the substance, but it ruled that, as Chamour's trainer, he "was none the less responsible for its presence".

The ban scarred O'Brien, then 43, and he even considered emigrating to America. As the Turf Club's many critics pointed out, O'Brien had little to gain from doping in such a minor race, as proved when the colt went on to win the Irish Derby, trained by Phonsie.

O'Brien returned to training at Ballydoyle in May 1961. A year later he won his first Derby with Larkspur, owned by the US ambassador to Ireland, Raymond Guest.

As President Kennedy was touring Ireland, Guest was unable to be at Epsom. Guest didn't have another horse in training with O'Brien for five years. Incredibly, that horse proved to be another Derby winner, Sir Ivor – among the many horses to benefit from O'Brien's innovative techniques as he spent the winter in the warmer climate of Italy. The experiment paid off, Sir Ivor also winning the 2,000 Guineas and the Champion Stakes.

He was the first O'Brien Derby winner ridden by Lester Piggott. Two years earlier, the Noel Murless/Lester Piggott partnership had broken up because Piggott elected to ride Valoris for O'Brien in the 1964 Oaks in preference to Murless's Varinia. Valoris won the race with Varinia third.

With so many top-class colts, it is easy to forget that O'Brien also trained outstanding fillies. He won the Oaks twice with Long Look (1965) and Valoris, and the 1966 1,000 Guineas with Glad Rags. Abergwaun (1972 Vernons Sprint Cup) and Lisadell (1974 Coronation Stakes) were other big race fillies trained by O'Brien, as was Lady Capulat, who won the 1977 Irish 1,000 Guineas in her first race. She was one of O'Brien's 27 Irish Classic winners.

In Britain, too, the top juvenile races were farmed by O'Brien, particularly the Dewhurst Stakes, which he won seven times. His first winner in the Newmarket race was Nijinsky, a colt as brilliant as his human namesake.

Nijinsky was owned by another American, the platinum king Charles Englehard. O'Brien first set eyes on Nijinsky in 1968. He had been asked by Englehard to look at a yearling colt. Instead he saw a son of the Kentucky Derby winner Northern Dancer and recommended Englehard buy him – Nijinsky – instead. As O'Brien was to demonstrate at the Keeneland sales in the next two decades, he was a master at spotting a young horse's potential.

With his partnership with Piggott – sometimes love/hate but perhaps the greatest combination in racing history – fully established, O'Brien trained Nijinsky to win all five of his-two-year-old starts. The best was yet to come. Nijinsky is the last horse to have won the Triple Crown of the 2,000 Guineas, Derby, and St Leger. In the Guineas and Derby, Nijinsky unleashed brilliant finishing speed to waltz past some top-class colts. He beat the older horses in the King George, but a bout of ringworm before he won the Leger took the edge off the colt. Nijinsky was still a narrow second to Sassafras in the Prix de l'Arc de Triomphe, when Piggott's riding was questioned, before ending his career with second in the Champion Stakes. Nijinsky, like many O'Brien colts, went on to be a successful stallion, his progeny including O'Brien's sixth and final Derby winner Golden Fleece.

O'Brien's fourth Derby win, and Piggott's third for the trainer, came with Roberto in 1972. This was a controversial win as Roberto's regular jockey Bill Williamson had been injured days before the race but was "jocked off" unfairly in many peoples' view.

The O'Brien/Sangster era began in 1975 when "the syndicate" (the third permanent member was O'Brien's son-in-law, John Magnier) decided to plunder sons of Northern Dancer-line sires at the Keeneland sales and syndicate the successful ones. Magnier has become perhaps the most influential figure in the bloodstock world, running the omnipotent Coolmore Stud.

From the first crop of yearlings they bought came Derby winner The Minstrel. He had disappointed in both the English and Irish 2,000 Guineas and only really ran in the Derby at the insistence of Piggott. Piggott won by a neck from Hot Grove. Having been bought for $200,000 by the syndicate as a yearling, The Minstrel was syndicated for stud at a value of $9m.

As well as The Minstrel, the first crop of three-year-olds included Alleged, a late maturing horse who went on to win the Prix de l'Arc de Triomphe twice. Alleged was bought as a yearling for $120,000, and retired with a valuation of $16m. Perhaps the greatest coup concerned the two-year-old Storm Bird, who disappointed at three. Bought as a yearling for $1m, he was syndicated for stud at $18m.

It was a lucrative period for O'Brien, who had a 10 per cent share in these horses. He was the first trainer to own shares in his horses on such a scale, having been advised by one of his owners, Jack Mulcahy, "to get a piece of the action". O'Brien described Mulcahy's words as "the best advice I ever got".

The Sangster syndicate, with all horses trained by O'Brien, dominated European racing between 1978 and 1985. Its winners included the Derby winner Golden Fleece (a $500,000 yearling and $28m stallion); the French Derby winner Caerleon (a $500,000 yearling, syndicated for $18m); and the Eclipse winner Sadler's Wells. There were inevitably disappointments, however, and when O'Brien and Sangster lost a duel with the Arab owner Sheikh Mohammed for the $10.3m dud Snaafi Dancer in 1983, it was clear the syndicate's number was nearly up, thanks to the oil wealth of the Maktoum brothers.

In 1984, O'Brien came close to winning his seventh Derby, when the brilliant 2,000 Guineas winner of that year, El Gran Senor was outstayed by Secreto. It was a day of mixed emotions for O'Brien. He had seen millions wiped off the potential value of El Gran Senor, but Secreto was trained by his oldest son, David. However, shortly after Secreto's career was over, David ended his own as a trainer, unable to handle the public pressure. He now concentrates on producing wine. O'Brien's other son Charles, who acted as his father's assistant, set up as a trainer in 1993, and has pursued a career on a lower level than his father.

El Gran Senor was the last great horse O'Brien trained. But there was one final emotional triumph, when Royal Academy won the 1990 Breeders' Cup Mile in America. He was ridden by Lester Piggott in the first season of his comeback as a jockey.

Royal Academy was owned by the publicly quoted company Classic Thoroughbreds, which had been set up by O'Brien, Sangster, Magnier, and the Dublin firm National City Brokers. O'Brien acted as chairman and trainer, but his 12 per cent stake ultimately brought him little return. The company was wound up in 1991, an abject failure despite Royal Academy.

Towards the end of his time as a trainer, O'Brien trained just over 10 horses each season at Ballydoyle. It was a low-key end to a high-flying career, but appropriate to O'Brien's character. The world of racing can be lurid and flamboyant, but O'Brien was quiet and shy, a devoted family man whose genius with horses made him one of the greatest ever trainers.

Richard Griffiths

Michael Vincent O'Brien, racehorse trainer: born Clashgannif, Churchtown, County Cork 9 April 1917; married 1951 Jacqueline Wittenoom (five children); died 1 June 2009.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments