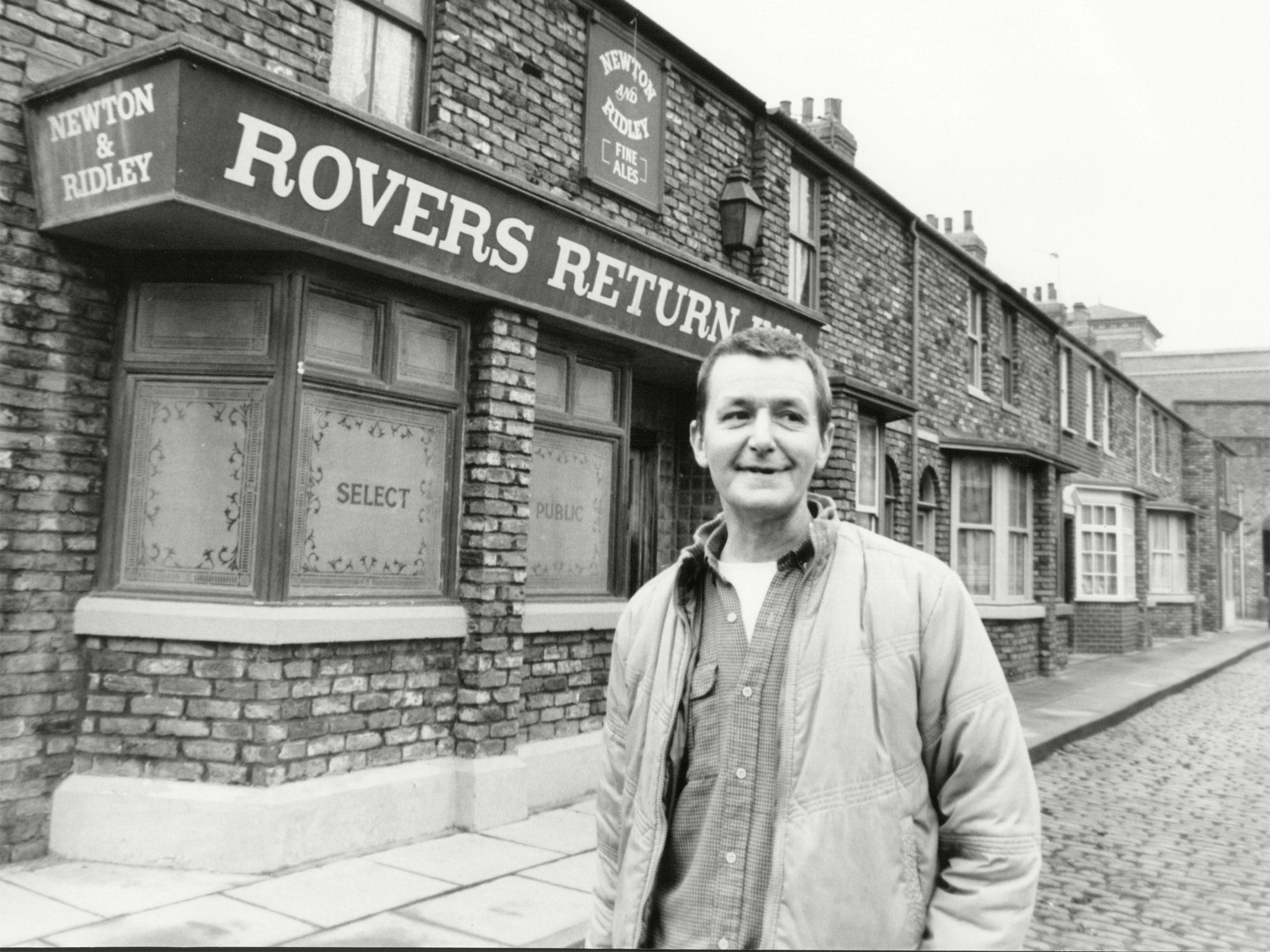

Tony Warren: Writer whose vision of a drama about a northern working class community became Coronation Street

The saga of Warren's crusading belief in his idea, his determination to see it realised authentically, and its eventual success, is a television fairy tale

The impact that Tony Warren has had on television is incalculable. At 22 years old, travelling back to Manchester by train one night with a BBC producer, Olive Shapley, he dreamed up a series, telling her: "I can see a little back street in Salford, with a pub at one end and a shop at the other, and all the lives of the people there, just ordinary things." She told him it sounded dreadfully boring.

It was, however, precisely the right time for a show so ahead of its time. Granada Television was a powerhouse of invention, fiercely committed to its local audience. Harry Elton, one of a number of astute Canadian producers working in British television at the time, commissioned Warren to write 13 episodes of Coronation Street. After the first was broadcast, a pained Daily Mirror critic famously wrote: "the programme is doomed from the outset... with its dreary signature tune and grim scenes of a row of terraced houses and smoking chimneys. For there is little reality in this new serial, which apparently, we have to suffer twice a week." This week it reached its 8,850th episode.

Tony Warren was born Anthony McVay Simpson in 1936 in Pendlebury, near Manchester. His grandfather was a champion clog dancer, his father a fruiterer who played the musical saw on the side. Unhappy at grammar school, he felt at home when he was moved to the Elliott-Clarke theatre school in Liverpool, and soon found professional acting work as a regular voice on BBC Radio's Children's Hour. At 15 he ran away to London, where his Peter Pan features kept him in work as a faux-juvenile until they matured strongly enough for him to become a male model.

That daydream on a night train about a series set in a Manchester back street came to him in 1957. He took it to a BBC still five years away from being able to comprehend doing everyday working-class drama (it would take another Canadian, Sydney Newman, to boot BBC drama out through the French windows and into the kitchen sink). Instead, Warren went to Granada, where he was hailed as their youngest ever scriptwriter with his first script, an eyebrow-raising two-part story of prostitution for the crime series Shadow Squad.

But it was not where his heart lay. Shadow Squad was referred to by jaundiced actors as "Shoddy Squad", and becoming a staff writer on the children's series Biggles (1960) frustrated him even more, as he seemed to have graduated from child actor to children's storyteller. Finally however, he persuaded Granada (through tantrums as much as talent) to make a pilot for his dreamchild, initially called Florizel Street.

In his pitch, he wrote: "A fascinating freemasonry, a volume of unwritten rules. These are the driving forces behind life in the working class street in the north of England. The purpose of Florizel Street is to examine a community of this nature, and to entertain."

Warren played a huge part in Coronation Street's realisation as well as its creation. He was responsible in particular for casting Violet Carson as the fearsome Ena Sharples. Those early (live) episodes belong as much to British social realist drama of the era as Look Back in Anger on stage and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning in the cinema; particularly electrifying in the early days were the clashes between Ena and Pat Phoenix's brassy Elsie Tanner.

The saga of Warren's crusading belief in his idea, his determination to see it realised authentically, and its eventual success, is a television fairy tale, and on the programme's 50th anniversary, BBC4 paid tribute to the show it turned down with a beautiful drama, The Road To Coronation Street, Warren played with an impeccable blend of attack and insecurity by the compelling David Dawson.

In one magical scene, Harry Elton (Christian McKay) is on the telephone ordering the unbroadcast pilot episode to be wiped, when he realises that his tea lady is mesmerised by it. "Is it the son they're rowing about?... we've got the same clock in our parlour," she murmurs. Scripted by Daran Little, the scene said it all. Within a few months Coronation Street was dominating the ratings without any concessions to audiences beyond the North-west.

Warren continued to write for the programme for a few years, but never managed to find another mantle beyond being the creator of the most successful British television programme of all time. He was hired to devise a film for Gerry and the Pacemakers, Ferry Cross the Mersey (1964), which tried but failed to replicate the charm and panache of A Hard Day's Night.

More interesting was the clunkily titled The War of Darkie Pilbeam (1968), a nostalgic triplet of wartime plays about keeping the home fires burning, focusing on spivvery and, like Coronation Street, putting the women centre stage. Warren explained that "in my blitz-ridden childhood, the area leading down to the Manchester docks was dubbed the Barbary Coast. For me it was a place of dark and wicked drama. It consisted of two theatres, a market, a sometimes fairground, and the knowledge that this was where the spivs conducted strict cash black market deals in shop doorways".

That kind of beer-battered romanticism hinted that Warren's gifts would be suited to writing novels. Finally, after many years lost to alcohol and drug problems, he returned in the 1990s with a run of novels beginning with the semi-autobiographical The Light of Manchester (1991), which became a Sunday Times Pick of the Year.

Warren was open about his homosexuality from the off, and faced prejudice and hostility from some quarters early in his career. He said in 2010 that "in those days, if you were going to work in television and you were gay, you had to be three times as good as anyone else." But he also suggested it had informed his writing, because "the outsider sees more."

When reviewing The Road to Coronation Street, The Guardian considered that evening's episode of the soap itself, and said that as it is today, "You couldn't really accuse it of... reflecting the ordinary lives of ordinary people".

Television is no longer as interested in everyday stories as sensational ones, often upping the stakes so high as to go into cloud cuckoo land. But what still remains in Coronation Street today is that essential blend of identifiable characters, fizzing dialogue and Northern soul: three things which will always carry Tony Warren's signature on them.

Anthony McVay Simpson (Tony Warren), writer: born Pendlebury, Greater Manchester 8 July 1936; died 1 March 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments