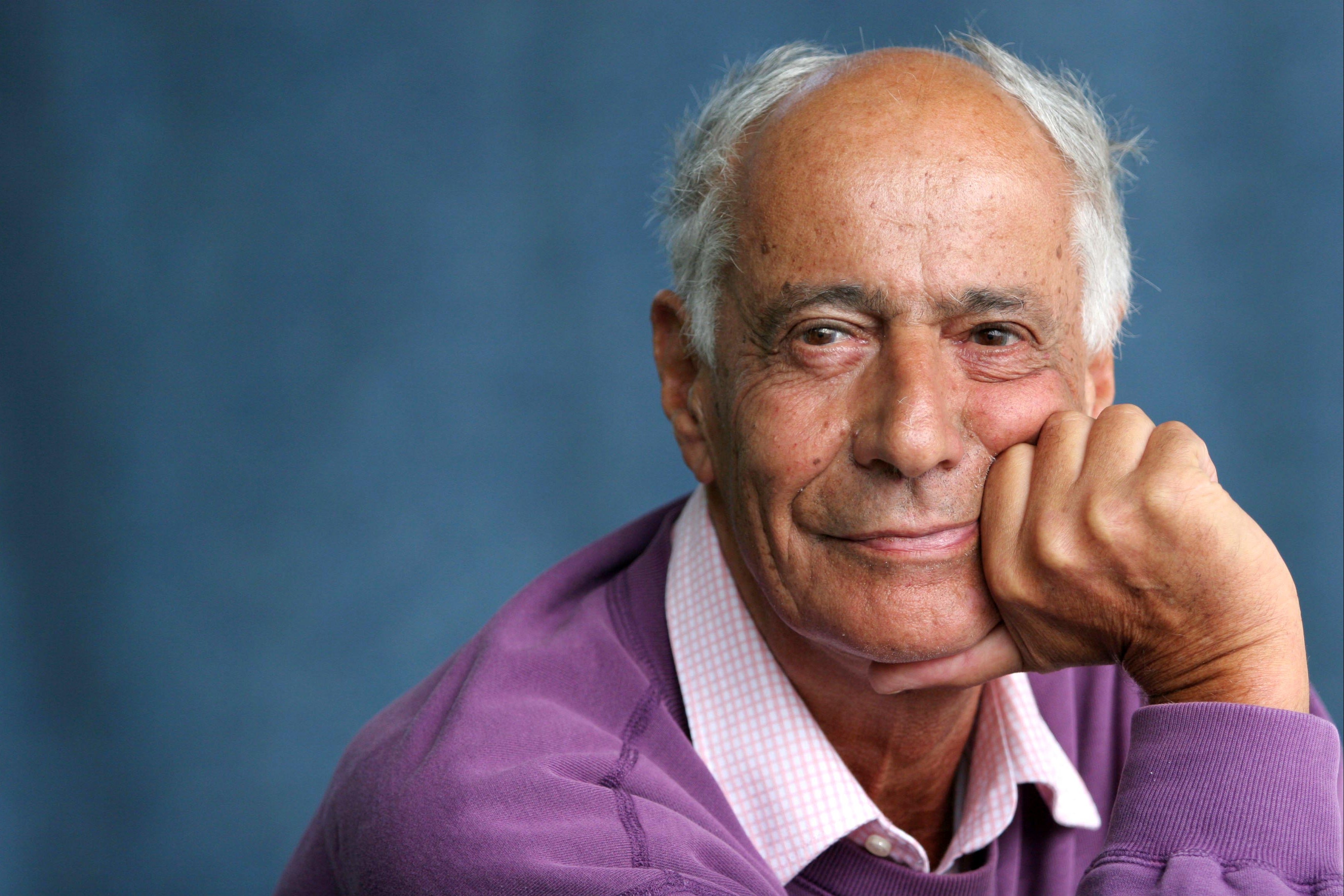

Tom Maschler: Publisher who was instrumental in founding the Booker Prize

Almost as well known as his writers, he was regarded as one of the most discerning literary talent scouts on either side of the Atlantic

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Tom Maschler was a publisher who propelled the careers of renowned writers and was a principal creator of the Booker Prize.

Maschler, who died on 16 October at the age of 87, was a German-born emigre whose father had been a successful publisher in Europe. After coming to England as a child, Maschler reluctantly entered the family trade after being a tour guide and failing to become a film director.

In 1960, when he was 26, Maschler became the literary director of the British publishing house of Jonathan Cape, after the death of its eponymous founder. Within a year, he began to restore the fortunes of the fading firm.

First, he bought the rights to Joseph Heller’s debut novel, Catch-22, for £250. When the book was published in 1961, it immediately became a No 1 bestseller in Britain.

“It was a genuine word-of-mouth success and had a buzz about it in the literary world before publication,” Maschler told The Guardian in 2005. “I am not aware of another book by an American writer that became a great success in England before it did in America.”

Also in 1961, Maschler was invited by Mary Hemingway to visit her home in Idaho soon after the suicide of her husband, Ernest Hemingway. Maschler helped her prepare Hemingway’s memoir of his years in Paris, A Moveable Feast, for publication. The book was a major literary event when it was published in 1964.

In Britain, the hyperactive, deeply tanned Maschler was almost as well known as his writers. Regarded as one of the most discerning literary talent scouts on either side of the Atlantic, he discovered or helped advance the careers of such acclaimed authors as Vonnegut, Garcia Marquez, John Fowles, Thomas Pynchon, Ian McEwan, Edna O’Brien, Clive James, Martin Amis, Julian Barnes, Salman Rushdie and Bruce Chatwin.

“In the office he was like a mad genius who would run around like an out-of-control windmill scattering pages of typescript on your desk and barking, ‘I urge you to read this. I urge you to read this,’” onetime publicist Polly Samson told The Guardian. “And if you didn’t read it that night he would think you were some sort of fool so you would. And you would always be glad that you had.”

Maschler once decided to publish an early work by Virginia Stephen, declaring she had extraordinary talent – without realising at the time that she was the same person as Virginia Woolf.

With a keen sense of marketing, Maschler published some of the first pop-up books. He commissioned zoologist Desmond Morris to write The Naked Ape, a 1967 nonfiction bestseller about evolution and human behaviour. As early as 1964, he was publishing writings by John Lennon. In 1969, he came out with the British edition of Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, which helped make the novelist a literary celebrity.

No fewer than 15 writers whose works were published by Maschler, from Garcia Marquez to Nadine Gordimer, Mario Vargas Llosa and VS Naipaul, received the Nobel Prize for literature.

“Tom had this extraordinary knack, without apparently being all that literary himself, of being aware of what was happening and seeing what was good,” a onetime colleague, Francis Wyndham, told The Guardian.

While visiting France in his late teens, Maschler noticed how the entire country was excited by the Prix Goncourt, an annual literary award. He thought Britain should have something similar and was instrumental in developing the Booker Prize, presented each year for the best work of fiction by a writer from the Commonwealth. (It was originally called the Booker-McConnell Prize, after a food company that was its sponsor, and was later called the Man Booker Prize. It is now known simply as the Booker Prize and has two categories: novels written in English and published in the United Kingdom or Ireland and novels translated into English from another language.)

Since the first Booker Prize was awarded in 1969, it has become an annual event along the lines of the Oscars. Bookmakers take odds on which writers will be named to the “shortlist”, the awards ceremony is televised and – true to Maschler’s vision – the winner and other finalists enjoy huge boosts in sales.

“The Booker may be the most important thing I’ve ever done,” he told The Guardian. “It certainly had an impact and if it means people think they should occasionally read a good novel, that is something I’m very proud of.”

Thomas Michael Maschler was born on 16 August 1933, in Berlin. His father, who owned two publishing firms, moved the family to Vienna in 1938.

Because of their Jewish heritage, the Maschlers were forced to flee Austria in 1939. Their house was seized by the Nazis, along with letters from such figures as Paul Cezanne, Vincent van Gogh and Thomas Mann. Three of Maschler’s grandparents died in the Holocaust.

The family ended up in England, and after Maschler’s parents separated in the 1940s, he lived with his mother, who worked as a housekeeper.

When Maschler was 12, his mother took him to Brittany, saying he needed to spend the summer learning French. She knocked on doors until she found a family that would take him in, then returned to England.

From then on, Maschler lived largely on his own. He attended a Quaker boarding school and excelled in tennis and other sports. He was offered a scholarship to the University of Oxford, but when he determined it was more for his athletic talent than his academic promise, he turned it down.

He travelled throughout the United States and Europe and by the time he was 20 had made a small fortune as a tour guide. After failing to break into the Italian film industry, he returned to England in 1955 and began to work in publishing. At Penguin Books, he made a literary splash by publishing the works of some of Britain’s rising dramatists of the 1950s, before joining Jonathan Cape.

“I think I can say there was something special going for Cape, from about the late Sixties to the Eighties, that made it a very potent place,” Maschler told The Independent in 2005.

He ran the publishing house until it was sold in 1988 and retained a connection with the company for many years afterwards. His autobiography, Publisher, appeared in 2005. For years, he divided his time between London and the south of France.

His marriage to Fay Coventry Maschler, a leading London restaurant critic, ended in divorce. Survivors include his wife since 1998, the former Regina Kulinicz; three children from his first marriage; and several grandchildren.

“I’m not a particularly scholarly person,” Maschler told The Independent in 2005, but he took offence whenever he was dismissed as a mere seller of books, someone whose abilities were limited to commerce rather than connoisseurship.

“My instincts in publishing are very much a gut reaction,” he said. “The only thing I can claim is that I have a very broad range, broader than most. Of course, some of it is pure luck. Luck is a word I like very much.”

Tom Maschler, publisher, born 16 August 1933, died 16 October 2020

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments