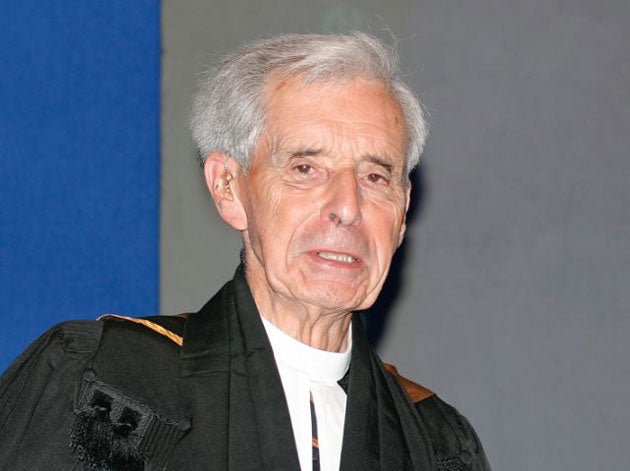

The Rev Arthur Macarthur: Minister who helped create the United Reformed Church

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

As a committed ecumenist, Arthur Macarthur was one of the principal architects of the United Reformed Church, which in 1972 brought together the Presbyterian Church of England and the majority of churches in the Congregational Church in England and Wales. His ecumenical activities also took him into the worldwide Church.

A walking tour in Bavaria in 1938 opened Macarthur's eyes to the realities of Nazi Germany, and as a Christian pacifist he worked with the YMCA in France, being caught up in the retreat to Dunkirk. Participation in the Agape youth project of the Waldensian Church in Italy in the aftermath of war was a reminder of that church's part in the Resistance, and he was present at the inaugural Assembly of the World Council of Churches at Amsterdam in 1948. He also attended the preparatory meeting for the Prague Peace Conference in 1958.

Two of Macarthur's later experiences, in the 1970s, illustrate the links between the Church and political reconciliation. In 1972 he was invited to visit the Presbyterian and Dutch Reformed Churches in South Africa. He made different visits to Soweto under the auspices of each church; both involved meetings with black pastors – and frank discussions. He was well aware of the problem of apartheid, but what struck him most was the separation between the English-speaking and Afrikaans-speaking whites; as one Presbyterian told him, "You have been here for a few days, but you have spoken to more DRC folk than I have in my whole life."

In 1969 he had become chairman of the Irish Advisory Group of the British Council of Churches; the most dramatic of the various meetings in which he was involved was with the IRA Army Council at Feakle, Co Clare, in 1974, the climax of which was the descent of 60 armed Irish police on the hotel after the main IRA leaders had hurriedly left. For Macarthur the consequences of this were not great, but for his Northern Irish Protestant friends they were much more serious. Politically the immediate gains may have been small – though the draft statement submitted to the Government was essentially similar to the Downing Street Declaration 20 years later; for the Irish Churches the gains were much greater.

This dimension of Macarthur's life is probably less well remembered than his pastoral ministry. Born into a Presbyterian family in Newcastle (his grandfather was also a Presbyterian minister), he felt the call to ministry early, and was supported in that by the sacrifices of his mother, despite his father's death when he was 16. At university on Tyneside in the depth of the Depression, he saw the harsh realities of working-class life. During an open-air campaign with the Student Christian Movement he found himself speaking on the opposite street corner to a local communist. He therefore went to Westminster College, Cambridge to train for the ministry with no illusions about the task facing the Church.

His first pastorate, at Clayport Street, Alnwick, was dominated by the Second World War but gave him early exposure to the beginnings of the British Council of Churches. New Barnet in the later 1940s offered the challenges of post-war reconstruction, and he took the initiative in taking out a five-year lease on a country mansion to serve as a Church Youth Centre.

St Columba's, North Shields, in the 1950s was different again. There he nurtured a new congregation at Chirton with the able assistance of Ella Gordon, whom he successfully proposed for ordination at the first woman minister of the Presbyterian Church of England. These pastorates were the prelude to the second half of his ministry as one of the General Secretaries of the English Free Churches – "the dissenting primates", as a Church of England bishop called them.

His experience as Convener of the Presbyterian Church's Inter-Church Relations Committee was one reason for his appointment as General Secretary, and most of the rest of his ministry was spent in the mechanics of church unions. As a member of the Congregational-Presbyterian Joint Committee appointed in 1963 to bring the two churches together he did not speak often in full committee, but at key points he made decisive interventions.

When the legal advisers explained the detailed legal process that union between the churches would involve (which took an hour), there was a pause. Then Macarthur said, "The two existing churches have to die in order to be born again". When moving the resolution in 1972 which declared that the United Church "is hereby formed", he boldly recognised that both traditions were moving into "something new and therefore unknown".

But, apart from the later unions of the United Reformed Church with the Churches of Christ and the Congregational Union of Scotland, subsequent efforts to secure wider Church union failed. Macarthur remained unrepentant about the emphasis that had characterised his ministry: the search for the unity of the Church, he said, "is part of the integrity of faith".

Macarthur had an active retirement, with a part-time pastorate in Marlow, Buckinghamshire. In 1986 he retired completely to south Gloucestershire, finding in the hills and dales a reminder of Northumberland. He may have seemed severe at first sight – Esmé, who was to become his wife for 58 years, had voted against his call to New Barnet because he seemed unfriendly – but there was always a twinkle in his eye. With the Northumbrian accent that remained with him, Macarthur was a man of craggy humour, shrewd judgement and absolute integrity. He never put himself forward, but, in the best sense of the word, he "empowered" others: he won the trust of everyone he met, and was a true friend to all.

David M. Thompson

Arthur Leitch Macarthur, minister of the church: born Newcastle upon Tyne 9 December 1913; ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church of England 1937; minister, Alnwick 1937-44; minister, New Barnet 1944-50; minister, St Columba's, North Shields 1950-60; minister, Marlow United Reformed Church 1980-86; General Secretary, Presbyterian Church of England 1960-72, Moderator, General Assembly 1971-72; General Secretary, United Reformed Church 1972-80 (jointly 1972-74); Moderator 1974-75; Moderator, Free Church Federal Council 1980-81; OBE 1984; married 1950 Esmé Muir (three sons, one daughter); died Cirencester, Gloucestershire 1 September 2008.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments