Sydney Brenner: Biologist who won a Nobel prize for bringing a worm to the attention of scientists

The South African, who studied in Britain, found in the microscopic Caenorhabditis elegans a model organism to aid the fields of neuroscience and animal development

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nobel laureate Sydney Brenner escaped poverty in his native South Africa – and apartheid, which he resisted by raising funds for black students – to become a pivotal figure in molecular biology’s golden era. With the help of a translucent soil worm, the scientist, who died aged 92 in Singapore, provided vital clues to understanding diseases such as cancer, Alzheimer’s and Aids.

When James Watson and Francis Crick’s clocked the double-helix structure of the DNA molecule in 1953, decades of scientific discovery followed to which Brenner’s findings were key. Not least among these was the “central dogma” of biology: the idea that our DNA code instructs the building of proteins that sustain life in our cells.

For nearly 40 years, Brenner was based at the MRC (Medical Research Council) laboratory of molecular biology in Cambridge, where he shared an office with Crick. A sign they kept – “Reading rots the mind” – belied their dazzling work in pushing the frontiers of their profession.

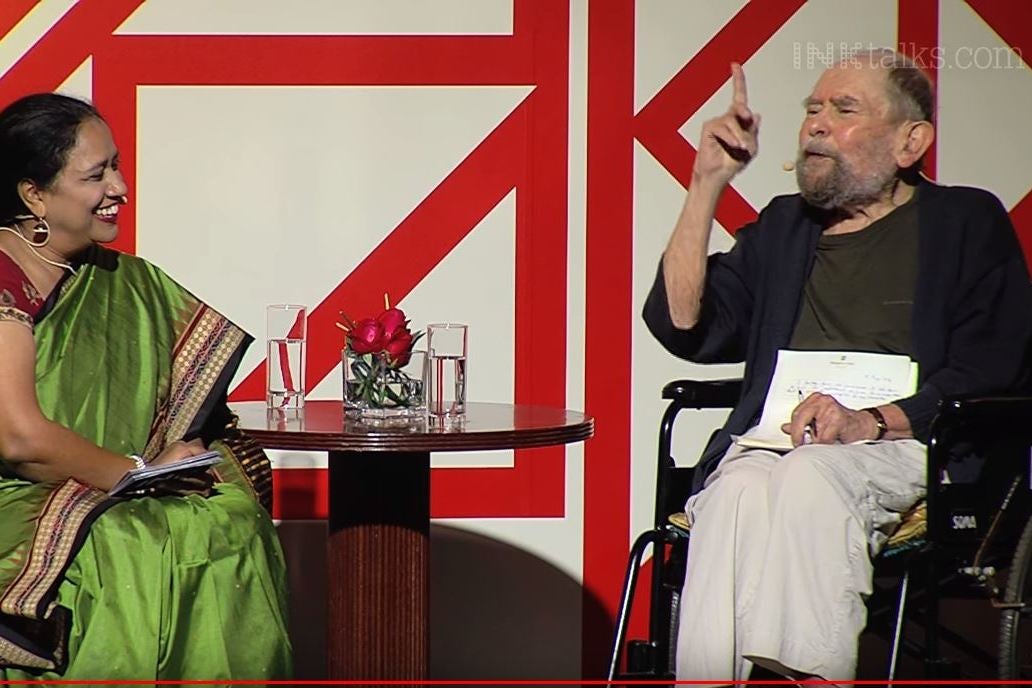

Showing similar irreverence, Brenner submitted a manuscript to the Royal Society in London with a fake reference – “Leonardo da Vinci (personal communication)”. When Brenner was awarded his second Lasker Award for medical science, the Nobel prize winner Joseph Goldstein described him as “chutzpah” personified.

Brenner’s biographer, Errol Friedberg, noted that his disdain towards rules made him the “scourge of universities and institution administrators”. Any flashpoints, however, tended to be overshadowed by the major advances Brenner made in molecular biology.

At the Cambridge lab in the late 1960s, he undertook an ambitious search for a model organism to study complex animal development on a genetic level – uncharted territory at the time. He found his match in Caenorhabditis elegans, a millimetre-long, transparent roundworm that would lead him to the 2002 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for “seminal discoveries concerning the genetic regulation of organ development and programmed cell death”, which “have shed new light on the pathogenesis of many diseases”.

Then affiliated with the Molecular Sciences Institute in Berkeley, California, Brenner shared the honour with John Sulston of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, and H Robert Horvitz of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

With the three men as its champion, C elegans pushed forward a new understanding of how our cells are programmed to proliferate, specialise and die. It became the first animal to have its complete genome sequenced – an important precedent for the Human Genome Project.

The humble worm’s DNA has turned out to be surprisingly similar to humans’ – an aid in understanding how our cells grow uncontrollably to cause cancer, and why they die in excess in neurodegenerative disorders, heart attacks and Aids. Picking the right animal to work on in biology, Brenner saw, was as important as asking the right questions.

“Without doubt,” he remarked in his Nobel lecture, “the fourth winner of the Nobel prize this year is Caenorhabditis elegans; it deserves all of the honour but, of course, it will not be able to share the monetary award.”

Sydney Brenner was born in Germiston, South Africa, in 1927, to Jewish emigre parents from eastern Europe. His father, a cobbler, could neither read nor write, although he could speak English, Yiddish, Russian and, after moving to South Africa in 1910, Afrikaans and Zulu.

The young man’s first home was in the back of his father’s shoe shop, two rooms he remembered smelling perpetually of leather. The public library became a haven, and it was there he found 1929’s The Science of Life, the three-volume tome, co-written by HG Wells, that first turned him on to biology.

Brenner entered medical school at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg aged 15. He did not like clinical practice, drawn as he was to the research lab. In 1952, he won a scholarship to study with chemist and future Nobel laureate Cyril Hinshelwood at Oxford. He received a doctorate in 1954.

In England, Brenner reunited with May Covitz Balkind, a fellow Witwatersrand student who had travelled to London to study psychology. They were married from 1952 until her death in 2010. Survivors include three children and a stepson.

Under Hinshelwood, Brenner joined a burgeoning group of thinkers who were forming the new field of molecular biology. On a cold morning in April 1953, he and three colleagues crammed into a car and drove to the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, England, to see Watson and Crick’s model of the DNA double helix with their own eyes.

The moment was “the watershed in my scientific life”, Brenner wrote in his biographical notes for the Nobel prize. Brenner joined the Cavendish Lab in 1957 and, in a collaboration with Crick that year, they deduced that DNA was read as a triplet code, with each unit of three bases (named A, T, C, or G) corresponding to one of 20 protein building blocks. The lab formally merged later with biology groups at the university to become the MRC laboratory of molecular biology.

With future Nobel laureate François Jacob at the Pasteur Institute and Matthew Meselson at Harvard, Brenner proved in 1961 the existence of “messenger RNA”. The molecule, they found, is a key intermediary between DNA and protein – a translated version of the genetic code that is sent out to direct synthesis in the cell’s protein-making factories.

Brenner’s greatest skills, as he described in his 2001 memoir, My Life in Science, were in “getting things started”. For him, the fun of science was in “the opening game”.

And so with a basic understanding of DNA worked out by the late 1960s, he turned his sights towards a new project: studying the development, especially the brains, of higher organisms. After abandoning more exotic animal models, Brenner looked to roundworms, recruiting his children and friends to collect soil from their backyards and holidays abroad. He settled upon C elegans: a fast-growing, self-fertilising, transparent creature with a simple nervous system that could be seen under an electron microscope.

From tip to tail, Brenner’s team mapped the entire cellular anatomy of the worm’s brain and spinal cord. Worms with strange morphologies or behaviours, such as abnormal locomotion or feeding, were of special interest.

From these specimens, Brenner worked backward to figure out which faulty neurons might cause the behaviour, and then which genes in those neurons had been mutated.

In Cambridge Brenner advised John Sulston, who developed techniques to trace all of C elegans cell divisions from the fertilised egg to the 959-cell adult. The feat has yet to be repeated in another organism. Horvitz, also a researcher on Brenner’s team, went on to identify key C elegans genes involved in controlling cell death.

In addition to his work in research, Brenner held leadership positions at the Medical Research Council in Cambridge. In 1996, he founded the Molecular Sciences Institute in Berkeley, California. He remained director there until 2001, when he joined the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California. His old friend Crick, who died in 2004, was also working at the Salk Institute.

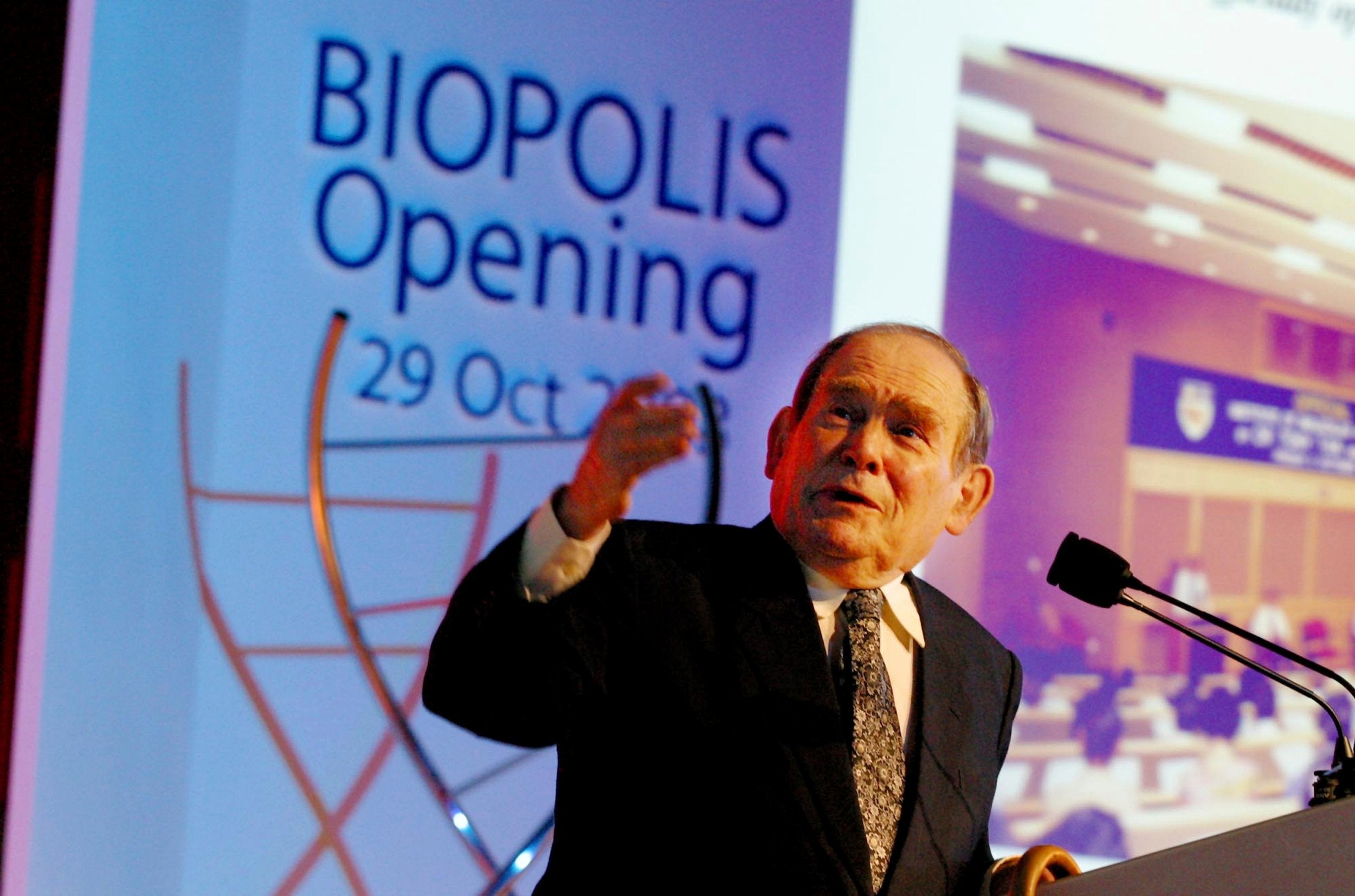

Brenner also helped launch the Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology in Singapore, where he became an honorary citizen.

In the 1990s, Brenner wrote a column in the journal Current Biology called “Loose Ends” (later renamed “False Starts”). The most popular of his pieces were his “Uncle Syd” columns, a series of letters to his imaginary advisee, “Dear Willie,” with practical-joke ideas and career tips for the young scientist as he rose from graduate student to retired professor.

To busy scientists seeking a polite way to turn down time-consuming invitations to meetings, he suggested the following reply: “Dear X, I regret I am unable accept your invitation as I find I cannot attend your meeting. Yours sincerely.”

Colleagues lauded him as “the funniest scientist who ever lived”, a title Brenner much preferred to “the father of the worm”. Behind the wisecracking exterior was a scientist who believed fervently in solving problems but who knew when to move on from a conundrum and leave it for younger minds to fiddle with.

“I’m a strong believer that ignorance is important in science,” he told The New York Times in 2000. “If you know too much, you start seeing why things won’t work. That’s why it’s important to change your field to collect more ignorance.”

Sydney Brenner, biologist, born 13 January 1927, died 5 April 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments