Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

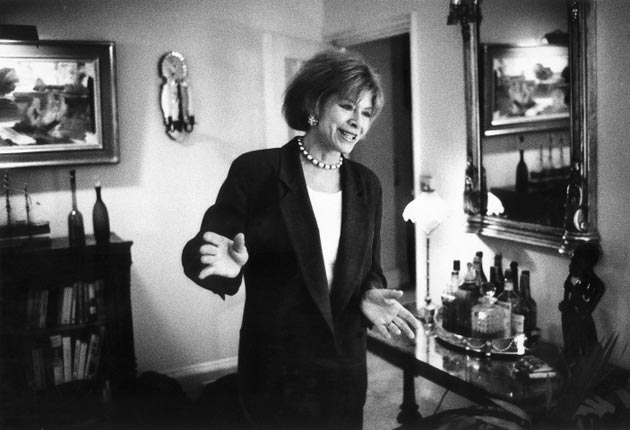

Your support makes all the difference.Susan Crosland had a long career as a journalist and later as a biographer and novelist.

She was best known to the public at large for her regular Sunday newspaper profiles, and for her affectionately informal and revealing 1982 biography of her late husband Anthony Crosland (1918-77), the Labour politician and cabinet minister, whose career culminated as Foreign Secretary in the 1976 Callaghan government.

Susan Barnes Watson was born in 1927 in Baltimore into a distinguished family of journalists. Her father, Mark Watson, won a 1945 Pulitzer Prize for his war reporting on the Baltimore Sun, where her mother, born Susan Owens, was also a reporter. Like most border state cities before the Civil Rights movements of the 1960s, Baltimore had the gracious atmosphere of a town of the Old South – at least for upper middle-class white families. At 18, Susan had a riding accident that had serious consequences for her late in life. She was sent away to university at Vassar, one of the smart "Seven Sisters" women's colleges, graduating in 1950; her first job was a teaching post at the celebrated Baltimore Museum of Art.

While there she met, and in 1952 married, her first husband, Patrick Skene Catling, the well-known children's writer. London-born, but educated at the progressive Oberlin College in Ohio, he was then working as a reporter on the Baltimore Sun alongside Susan's father. The couple spent four years in Baltimore, but her husband was frequently away on assignment, including covering the Korean War. This was a time when the great metropolitan American newspapers maintained their own overseas bureaux, and in 1956 Catling got the plum appointment as London correspondent of the Sun. Susan joined him with their two young daughters, and they loved London. However the Sun, in common with most American papers, had a policy of rotating their staff, so as to keep them from going native and losing their American slant on the events they reported – two years in London was their ration.

By 1958, when the glamorouscouple had to leave, they kneweverybody in the social and political worlds of the capital. Susan had met Anthony Crosland at a party given by some Vassar friends at the acme of the Suez crisis. On that occasion she asked the dashing but sometimescutting Labour MP if his great work, The Future of Socialism, was apamphlet; though he gave her an annotated copy of his book, her gaffe did not matter, as they had both experienced a coup de foudre. Crosland gave a bon voyage party for the Catlings at his flat in the Boltons. The impressively catholic guest list for the party included the leader of the opposition, Hugh Gaitskell, plus a sprinkling of aristocrats.

Crosland was so taken with Susan that he persuaded his friend, Lady Jane Butler, the beautiful and adventurous daughter of the Marquess of Ormonde, to join him the next day in chartering a plane to take them to Cannes, to say goodbye yet again, before the Catlings returned by sea to Baltimore. Jane told me that when she later visited them in Baltimore, she was proud to have been given the key to the city by the Mayor.

Their marriage was already in trouble, but they were determined to return to Britain, and Catling managed to get a job in London with the Manchester Guardian. Badly needing more money, Susan got work on the Sunday Express, dazzling its editor John Junor with her looks, quick wit and a CV claiming experience in journalism that she did not have. After her first effort, a travel piece, she was given a contract. Mostly she wrote interviews, using the byline "Susan Barnes" to avoid the appearance of cashing in on her father's eminence. (The "Susan Barnes Interview" appeared regularly in the Sunday Express until she and Crosland married, and he asked her to leave it, as he felt it was awkward for her to be on a Conservative paper while he was hoping for a place in a Labour cabinet.)

When she went up to Grimsby to canvass for Crosland in 1959, her appearance and accent dumbfounded his agent, but he held the seat for Labour by 101 votes. Catling was away on assignment that autumn when she had a burst appendix, and she could think of no one to give the hospital as next of kin except Hugh and Dora Gaitskell. Gaitskell and Crosland drove her home after her operation; and soon after Catling returned to America to work for the singer, Peggy Lee, whom he announced he was going to marry (but never did).

Crosland had married Hilary Sarson in 1952, but they were not divorced for five years, and he was known to have a busy and varied romantic life. He and Susan finally married on 7 February 1964 at Chelsea Register Office. Their witnesses were the ebullient Dora Gaitskell, and Ruth, the widow of Hugh Dalton. Crosland first became a cabinet minister in January 1965, as Secretary of State for Education and Science, whereupon Susan withdrew her children from their private schools and sent them to state schools at 11, so as not to embarrass her Socialist husband.

She moved to the pre-Murdoch, broadsheet Sun, and remained there until 1970, when she joined Harold Evans's Sunday Times, where she came into her own and wrote long profiles of public figures with sensitivity and brio. Her interviewing technique was to ask lots of questions that struck the interviewee as irrelevant, or even (in their Notting Hill neighbour Tony Benn's case) trivial. In the end, though, her subjects nearly always revealed their real character to her; or, if they were hiding something, whatever it was they least wanted to make public.

Benn had, unusually, been promised that he could read the piece about him before publication. He recorded in his Diaries for 1965 that he found it "the bitchiest, most horrible thing I've ever read" and he asked her not to publish it. But on the whole, thicker skins prevailed, and many readers turned to her pieces first on Sunday mornings. Her pieces on Richard Crossman, Jeremy Thorpe, John Betjeman and Kenneth Tynan can all stand up to re-reading. When Crosland became a cabinet minister he insisted that his wife should be independent of any paper, at least to the extent that she was on a freelance contract, and not a member of staff. But they did need the second income, so she continued to work as a journalist almost throughout their marriage.

Though Crosland was celebrated for the towering intellect that got him a first in PPE at Oxford in 12 months, and though the sexual attraction was obvious to all who knew them, he also regarded Susan as his intellectual peer. The importance of this aspect of their relationship was apparent when, following his shocking death, aged only 58, in 1977, the still-grieving Susan decided to write her biography, Tony Crosland (published in 1982).

In it she dealt with his odd upbringing, his parents belonging to the Exclusive Brethren sect (he is supposed to have bristled when he found her reading Father and Son, Edmund Gosse's classic account of growing up in this milieu, as he knew she was researching his background). She wrote about his time at Highgate School, Oxford, both before and after his war service as a paratroop officer; about the nasty internecine struggles in the Labour Party that resulted in Harold Wilson's victory – though Crosland regarded himself as a radical, not as a right-winger; and she wrote about the embarrassing George Brown in Crosland's first government job at the Department of Economic Affairs. Political reviewers of her book said it made a genuine contribution to understanding the politics of the Labour Party. She was invited to stand as a Labour candidate herself, and a peerage was offered: both were declined.

In July 1976, at a banquet for President Ford given by the Queen at the Washington Embassy, Susan fainted, fell and broke her jaw. This was an indication that all was not well with her; but she was also not well off. Her husband's estate was only £78,000, and though she made £45,000 from the sale of serial rights to Tony Crosland to the Sunday Times, she had to go back to work. She went back to writing profiles for the paper, now edited by Andrew Neil, and scored successes with pieces about Michael Heseltine, Nigel Lawson and Paul Johnson. But she had ambitions as a novelist, and produced four would-be blockbusters, Ruling Passions (1989), Dangerous Games (1991), The Magnate (1994) and The Prime Minister's Wife (2001), none of which was anything like a best-seller.

However, she found it difficult to research her lengthy profiles and write fiction, so asked the Sunday Times instead for a weekly column. It was not a success. She did, however, gather both kudos and some cash for her two collections of profiles, Behind the Image (1974) and Looking Out, Looking In (1984). Great Sexual Scandals (2002) is better overlooked.

Though she was still creased with grief for Crosland when I first met her, in the late '70s, the second love of her life, with whom she took up in the mid-1980s, was another great journalist but failed novelist, Auberon Waugh. Their unlikely liaison was an open secret; Waugh lived with her a few evenings each week then returned to his wife in the country. The Prime Minister's Wife is dedicated to him.

Theirs was a deep friendship, lasting until his death in 2001, based on mutual aid and comfort. He had a weak and failing heart, and Susan was crippled by the arthritis that had resulted from her early riding mishap. She needed hip and shoulder replacements, and elected to have the operations in a London NHS hospital.This was a gesture to her latehusband's politics, and, she came to think, misguided, for she contracted MRSA. In late February 2007 she gave an interview to the Daily Mail, headlined: "I put my faith in the NHS – and it's crippled me."

The operations caused years of anguish throughout the 1990s, each having to be redone, and caused her much indignity, though she was able to laugh it off. (She famously told the Daily Mail interviewer that "Bron and I realised that if I could get some crotchless tights it would make my social life easier. Auberon volunteered to go to a sex shop and he came back, very pleased, with the tights. Nothing abashed him.")

She was not even daunted by the fact that one of the operations left her with one leg four and a half inches shorter than the other. Always careful about her appearance – she retained her looks into her old age – she wore a massively built-up shoe and called it her "Spice Girl shoe."

She was a Trustee of the National Portrait Gallery from 1978-1992, the sole appointment she listed in her modestly brief Who's Who entry.

Susan Barnes Watson, writer and journalist: born Baltimore, Maryland 23 January 1927; married 1952 Patrick Skene Catling (marriage dissolved; two daughters), 1964 the Rt Hon (Charles) Anthony (Raven) Crosland (died 1977); died London 26 February 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments