Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

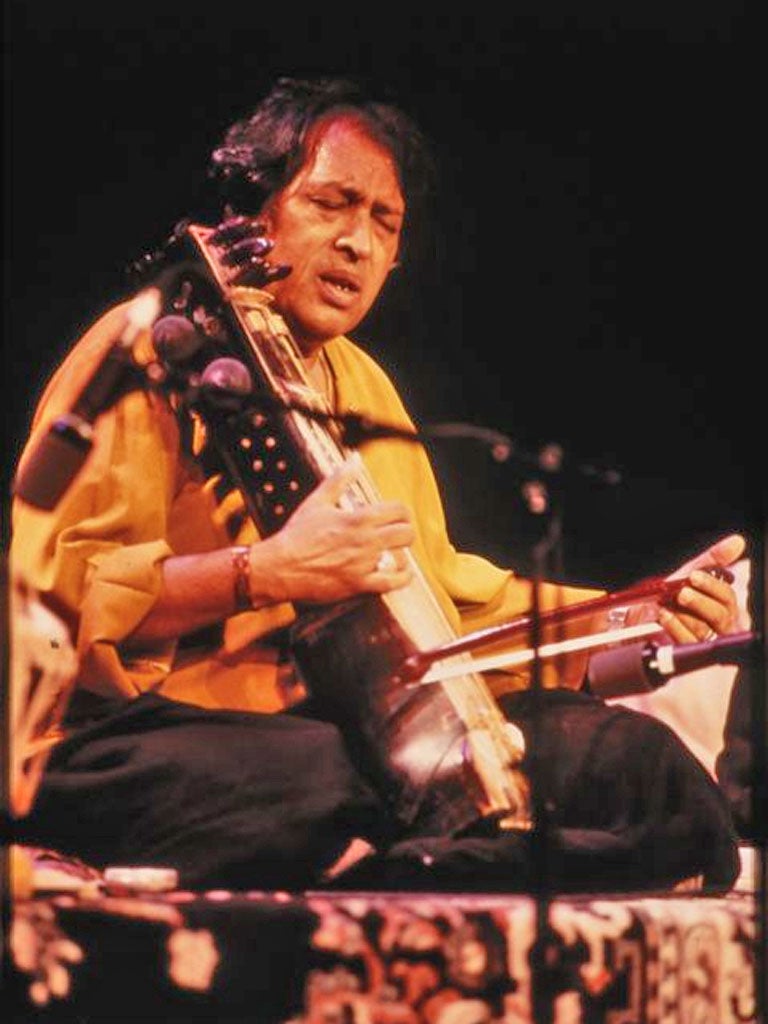

Your support makes all the difference.Sultan Khan was a hereditary sarangiya – a sarangi player – and one of the preeminent Hindustani or Northern Indian classical soloists of our age. He played one of the most brutish-looking instruments humanity has ever devised. Yet the voices that he coaxed from this squat, bowed, stringed instrument were divine. The instrument's name derives from two words meaning "100 colours", but Sultan Khan proved that the sarangi hid many more than that. Many hold it to be the instrument able to capture the nuances and tonal range of the human voice the most faithfully. Many – Mickey Hart, the Grateful Dead drummer-turned-Smithsonian Folkwayswallah who recorded him included – hold sarangi to be the greatest melody instrument ever devised. And without question, Khan was one of sarangi's all-time virtuosi.

Historically, sarangi – an instrument found in folk and classical forms across the north of the subcontinent – had a bad reputation by association. Sarangiyas accompanied nautch (dancing-girl) and tawaif (courtesan) entertainment. It was considered a lowly instrument and one not worthy of the classical recital dais. The sarangiya Ram Narayan began the instrument's slow elevation to the classical stage and revolutionised its appreciation in the immediate years after Partition.

Khan, who died at his Mumbai home at the age of 71 following chronic kidney problems, was the next generation. He was one of the most grounded musicians imaginable, and from first meeting him in 1981 I never heard him say a bad word about anybody. Building on Ram Narayan's work, he truly took the instrument abroad and brought it back home. He was one of Ravi Shankar's handpicked musicians who toured and recorded as part of the George Harrison/Ravi Shankar Festival from India package in 1974 (reissued on 2010's Shankar/Harrison boxed set Collaborations). He contributed to Tabla Beat Science, the illicit love-child of Zakir Hussain and Bill Laswell. For Seize the Time (1994), Fun-Da-Mental sampled a sarangi solo of his on "Fartherland", and he took it all in good spirit.

But it would always be in the classical realm that he was most at home. Steeped in Rajasthan's tight-knit Sikhar-based musical and caste traditions, he was a mirasi (hereditary professional) musician with forebears standing behind him when he played sarangi or sang. He had the gift and the touch. Early on, he was sought out as an accompanist by headliners such as the vocalist Amir Khan (himself a former sarangiya) and played sarangi to the later vocal maestro Pandit Jasraj's tabla.

He had an innate sense of rhythmicality as well. Perhaps the finest partnership of his musical career was the one he forged with the tabla virtuosi Alla Rakha (Qureshi) and Zakir Hussain (Qureshi), willingly subordinating his playing to their percussive eloquence.

He contributed music to a number of films, both as a sarangiya and vocalist. Like Ram Narayan, as Regula Burckhardt Qureshi explains in Master Musicians of India: Hereditary Sarangi Players Speak (2007), the Hindi film industry offered "anonymity for work that did not enhance their classical music standing." Khan's on-the-record credits included Richard Attenborough's Gandhi (1982); Merchant-Ivory's Heat and Dust (1983); Hindi films such as Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (1999); Manish Jha's arch Matrubhoomi: a Nation Without Women (2003); and Subramaniya Shiva's Tamil film Yogi (2009).

Music's powers can communicate across language barriers. In my life, the poignancy of Khan's artistry brought me to tears more than any other musician. The most remarkable experience occurred in 2001 at the London-based Allarakha Foundation's first commemorative celebration of Alla Rakha's life. Khan and his sarangi sang the Rajasthani lori (lullaby) "Soja Re" (Go to Sleep). He sang his friend home. It was cathartic – a release like unstoppering a bottle. Afterwards, the whole audience was wet-eyed and tear-streaked. In five decades of music criticism I have never witnessed its like.

He is survived by his second wife, Uma, and their two daughters, and sarangiya Sabir Khan from his first marriage. His son had been scheduled to play on Zakir Hussain's Masters of Percussion tour in November 2011 before his father's health deteriorated.

Ken Hunt

Sultan Khan, sarangi maestro: born Jodhpur, Rajasthan 15 April 1940; twice married (one son, two daughters); died Mumbai 27 November 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments