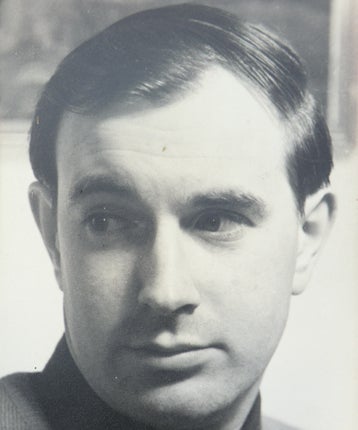

Stephen Wall: Critic and academic who edited the leading literary journal 'Essays in Criticism' for 37 years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For 37 years Stephen Wall served as the editor of Essays in Criticism, regarded as a leading journal in the field of English studies.

Such a record is almost unparalleled in modern scholarship and would be an impressive achievement by any reckoning. In Wall's case, it was combined with an extraordinarily productive life as teacher, literary critic and reviewer, theatre director, novelist and connoisseur of period musical instruments. He also served the cause of the disabled: in 1956, at the age of 25, he contracted polio. It was the last major outbreak before the introduction of the Salk vaccine in Europe; his case was severe, and he was to be confined to a wheelchair thereafter.

Born in 1931 to a Quaker family in Hampstead, Wall was educated at Quaker boarding schools, at Sibford, near Banbury, and at Leighton Park. Though he retained none of the Quaker faith he remained a nonconformist in attitude, and a pacifist. Awarded a scholarship to read English at New College, Oxford, Wall discharged his obligations in default of National Service as a conscientious objector by working as a hospital porter.

While still an undergraduate, he married Barbara Parrott in 1952. At Oxford Wall began his serious involvement in the theatre. After graduating he spent a year teaching, and working on a farm at Fencott, north of Oxford. In 1955 he obtained a position as lecturer in English at the University of Leiden, and it was in the Netherlands that he was stricken by polio.

In 1956 he was transferred to the Nuffield Orthopedic Centre in Oxford where he learned to use what muscles he still had. Among his fellow polio-victims in the same ward was the novelist JG Farrell, whose physiotherapist, Yvonne Rouse, would become Wall's second wife. In later years Farrell and Wall enjoyed fishing, though while Farrell braved Ireland's Atlantic coast, Wall was content with the upper reaches of the Thames. Farrell's death in 1979, swept from the rocks while fishing, was a great loss; earlier this year Stephen and Yvonne were delighted by the posthumous award to Farrell of the "Lost Booker Prize" for the best novel of 1970, Troubles.

After leaving hospital Stephen Wall courted and, in 1958, married Yvonne. He remained friends with Barbara. His marriage to Yvonne was to last for more than 50 years, and what he achieved, academically and beyond, depended on his wife's imperturbable devotion and unfaltering tact: the depths of such dependency can scarcely be fathomed by the able-bodied.

Wall enrolled at Oxford for the BLitt and there encountered as his supervisor John Bayley, who would become a valued colleague and friend. Wall began contributing book reviews to the weeklies, notably The Observer, The Listener and The New Statesman, and was widely respected as a critic of contemporary fiction; he also taught adult education classes for Oxford's University Extension courses.

He was appointed tutor in English at Mansfield College, where his gifts as a teacher quickly became apparent. In 1964 he was elected a Fellow of Keble College; there he tutored across a huge swathe of the English Literature syllabus, from Shakespeare to the present. His tastes and expertise were wide, though he was most at home with Shakespeare and the Victorian novel. His partnership with Keble's Fellow and Tutor in English Language, Malcolm Parkes, yielded an impressive number of Firsts and nurtured some distinguished careers: two of the Chairs of English at Oxford and Cambridge are held by their former students.

Though confined to a wheelchair, Wall was able to lead a life that more than matched the demands of his position. Able to drive, he could attend the theatre in London and Stratford; he regularly wrote drama reviews for the TLS and the Sundays. For some 20 years Wall lived so energetically that, unless one had met him, one would have had little sense of any disability. In the early 1960s he was involved with his close friend Ian Hamilton in founding The Review, for which he wrote; from 1974 he supported Hamilton's New Review. In 1970 he compiled the Penguin Critical Anthology on Charles Dickens, and in 1971 edited Anthony Trollope's Can You Forgive Her? for the Penguin English Library, for which in 1988 he also edited (with Helen Small) Dickens's Little Dorrit.

Invited to join the Editorial Board of Essays in Criticism in 1969, Wall became joint editor with FW Bateson in 1973. The journal, founded in 1951 by Bateson, quickly established a reputation which has been sustained ever since. During these years much has changed in the study of English literature, rather less in Essays in Criticism; it was (and is) the aim of Essays to offer resistance to the partisan and the fashionable, and to be a platform for debate in the spirit of Matthew Arnold, to whom the journal's title pays tribute.

Where other journals have changed with the times, Essays remains consistent, usually at a slight angle to the discipline, the "house style" characterised by a dryness of wit and a courteous allusiveness, all jargon eschewed. Wall was an exacting and diligent editor, stringent with contributors, considerate to readers. The journal's focus remains firm: English literature from Chaucer to the present. In the 1950s the present included Eliot and Auden, first as contributors and since as subjects. In recent years Geoffrey Hill has been prominent in both capacities. Over the years Essays has given space to critics as diverse as CS Lewis and William Empson, George Steiner and Raymond Williams, Gillian Beer and Terry Eagleton.

He was closely involved in the Oxford University Dramatic Society, for whom he directed Coriolanus in 1971, Othello in 1976, in 1979 (a theatrical first) Comedy of Errors together with its source, Plautus' Menaechmi, and in 1982 The Winter's Tale. Among those whose acting careers he nurtured are Hugh Quarshie, Diana Quick and Charles Sturridge; the screenwriters Frank Cottrell Boyce and Richard Curtis also learnt much. From 1974-87 he was Chairman of Anvil Productions, the professional company attached to the Oxford Playhouse.

For the Oxford Operatic Society Wall directed Purcell's Indian Queen, drawing on his knowledge of early music and performance history. With an expert's enthusiasm for period keyboard instruments, he and Yvonne formed a refined collection. They acquired a number of rarities, even rescuing from a canal boat two square pianos, one a Fröschle of 1772, subsequently donated to the Bate Collection of musical instruments in Oxford. Wall was a gifted sight-reader and a capable player.

In his fifties Stephen Wall found his energies diminishing, and he began to suffer from periods of fatigue. On medical advice he ceased to teach in 1989. His case, under scrutiny from Oxford's medical establishment, contributed to the identification, in the late 1980s, of post-polio syndrome, the secondary debilitation that can follow some 30 years after the initial infection. He ceased to undertake major theatrical projects, and completed a long meditated study of a favourite novelist: Trollope and Character (Faber, 1988) was well received. Its defence of Trollope's art is conducted with elegance, subtlety and humour, in sentences pithily epigrammatic or sinuously subtle. Few critics have commanded such a knowledge of the characters of all 70 of Trollope's novels, and thus been able to trace so acutely the patterns of repetition and recurrence.

For many years Wall lectured for the English Faculty on the novel from Jane Austen to Thomas Hardy, and he and John Bayley held a postgraduate course on the European novel. Their seminars were celebrated: the English-ness of their wit and manner displayed the more sharply the cosmopolitanism of their conversation. Wall was adept at turning his situation to dark comic advantage, as though even at the worst there could be some consolation in having been assigned a lifelong role in a play by Beckett. Of all writers it was Samuel Beckett whom Wall would cite most often; there was always a wry hint of identification with Beckett's trapped and immobilised characters. He did not commit his thoughts on Beckett to print, perhaps because it would have entailed something of the autobiographical.

He was seldom visible as a campaigner for the rights of the disabled, though he worked unobtrusively. As a member of the Disability Information Trust he would test out new technology and equipment. In 2000 he was invited to talk with the Prime Minister's advisors, and expressed his dismay at the Government's decision to withdraw funding from the Trust.

From the early 1970s the Walls spent their summers in a cottage overlooking the Black Mountains. There he took to fiction and in 1991 Bloomsbury published Double Lives. In 2007 a shorter work, En famille, appeared in Areté. Double Lives was well-received but wrong-footed some, for it discreetly deploys some of the devices of the nouveau roman; Wall particularly admired Claude Simon.

Though he gradually curbed his activities, Stephen Wall never retired. Rest was taken reluctantly. He worked into the last weeks: the July 2010 issue of Essays appeared on schedule.

Stephen de Rocfort Wall, literary critic: born London 29 July 1931; editor, Essays in Criticism 1973-2010; married 1952 Barbara Parrot (divorced 1958, one daughter), 1958 Yvonne Rouse (one daughter); died Oxford 6 August 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments