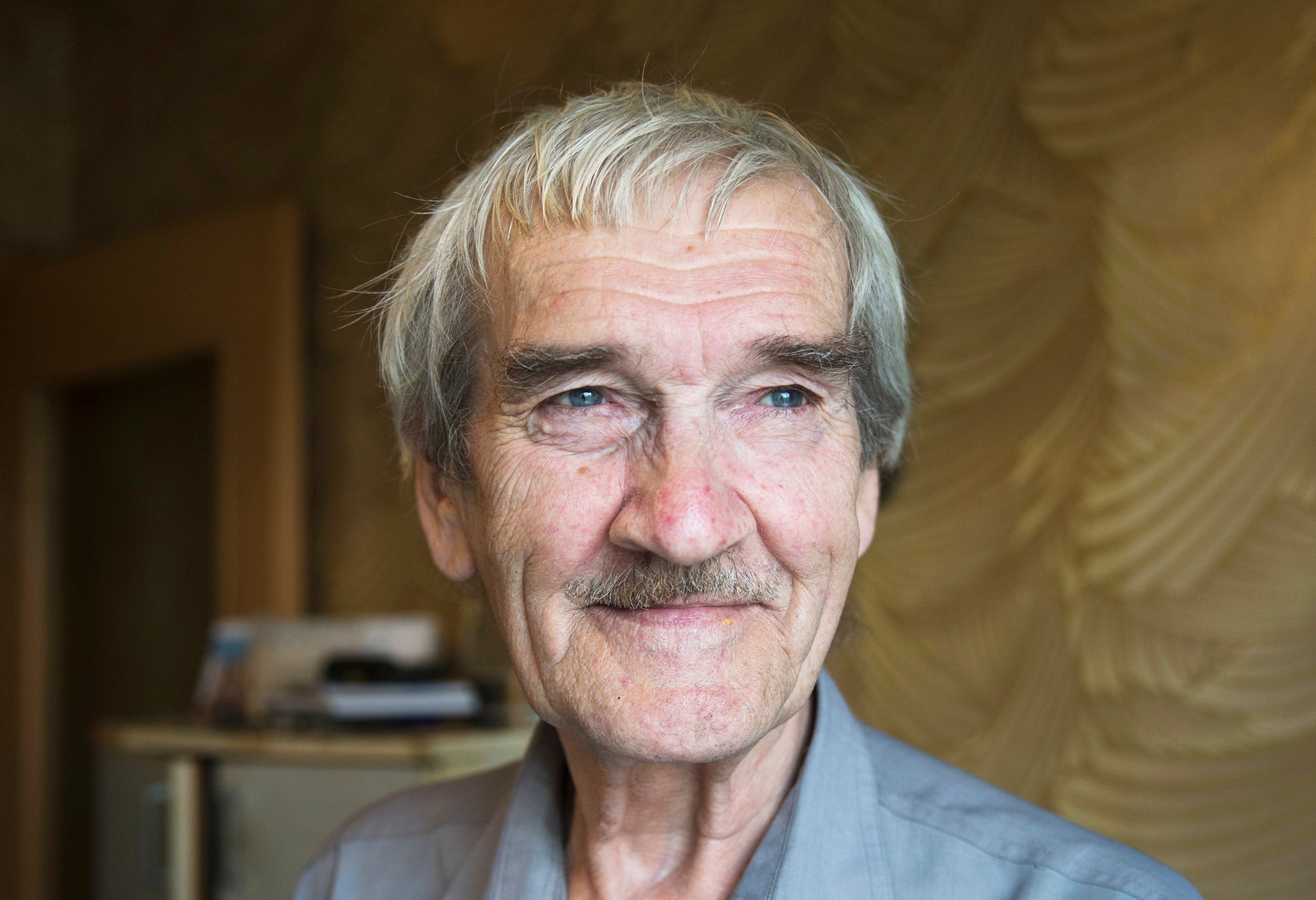

Stanislav Petrov: Soviet military officer who averted nuclear war

When Russia's nuclear early-warning system wrongly detected incoming US missiles, Petrov judged it was a false alarm

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When alarms began to ring and a control panel flashed in front of Stanislav Petrov, a 44-year-old lieutenant-colonel seated in a secret bunker south of Moscow, it appeared that the world was less than 30 minutes from nuclear war.

“The siren howled,” he later said, “but I just sat there for a few seconds, staring at the big, back-lit, red screen with the word ‘launch’ on it.” His chair, he said, began to feel like “a hot frying pan”.

Petrov, an official with Russia’s early-warning missile system, was charged with determining whether the United States had opened intercontinental fire on the Soviet Union. Just after midnight on 26 September 1983, all signs seemed to point to yes.

The satellite signal Petrov received in his bunker indicated that a single Minuteman missile had been launched and was headed east. Four more missiles appeared to follow, according to satellite signals, and the protocol was clear: notify Soviet Air Defence headquarters in time for the military’s general staff to consult with Yuri Andropov, the Soviet leader. A retaliatory attack, and nuclear holocaust, would likely ensue.

Yet Petrov, juggling a phone in one hand and an intercom in the other, judged that the red alert was a false alarm. Soviet missiles, armed and ready, remained in their silos. And American missiles, apparently minutes from impact, seemed to vanish into the air.

“I had a funny feeling in my gut,” Petrov told The Washington Post in 1999. “I didn’t want to make a mistake. I made a decision, and that was it.” He celebrated with half a litre of vodka, fell into a sleep that lasted 28 hours and went back to work.

While the “50-50” decision may have averted catastrophe, it ultimately destroyed the career of Petrov, who died on 19 May at his home in Fryazino, a centre for scientific research near Moscow. His death – much like the defining moment of his life – went largely unreported until his friend, the political activist Karl Schumacher, announced that he heard the news from Petrov’s son, Dmitri, and that Petrov had been sick for the last six months with “an internal disease”.

The colonel’s brush with history came six months after US President Ronald Reagan christened the Soviet Union an “evil empire,” and just three weeks after Korean Air Lines Flight 007 wandered into Soviet airspace and was shot down, deteriorating US-Soviet relations even further.

When Nato held a military training exercise known as Able Archer 83 that November, Soviet officials interpreted Western troop movements as preparations for a pre-emptive strike. The country began readying its expansive nuclear arsenal, and the West seemed primed to escalate its own efforts when an intelligence official in the US Air Force, Leonard Perroots, chose – like Petrov – not to respond to the apparent provocation. (The incident inspired a recent American TV series, Deutschland 83.)

Yet while Perroots was lauded at the time and went on to direct the Defence Intelligence Agency, Petrov became a pariah in the Soviet military, a scapegoat for what turned out to be a case of mistaken identity in the early-warning system’s software: instead of identifying a group of missiles, the software had spotted the sun’s reflection off the top of clouds.

Petrov said he was initially sceptical of the launch because only a handful of missiles had been fired – “When people start a war,” he told the Post, “they don’t start it with only five missiles” – and because Soviet ground-based radar had shown no evidence of an attack. But a military investigation chastised and eventually reassigned Petrov, in large part for not keeping a detailed log of his actions during the five minutes it took him to decide the alarm was false. (His hands were full, he said.)

He had also thwarted a protocol that was designed to take such a weighty decision out of the hands of humans. A computer, not an individual officer, would decide whether missiles were imminent, and thus whether retaliatory action might be necessary.

In later years, Petrov sometimes said that he was simply “in the right place at the right time”. Most of his comrades, he said, would probably have confirmed the approaching missiles rather than questioned the alerts from the computer. In fact, according to Peter Anthony, a Danish filmmaker who directed The Man Who Saved the World, a 2014 documentary on Petrov, he wasn’t supposed to be there in the first place. “Another officer was sick,” Anthony said, “so Stanislav had to take over.”

Stanislav Yevgrafovich Petrov was born in 1939 in Chernigovka, an air base north of Vladivostok. His mother was a nurse, and his father was an aviation engineer who had flown fighter planes during the Second World War. (He was once shot down by the Japanese, resulting in a severe head injury and an admonition to his aviation-minded son: never fly.) When his mother became pregnant with a second child, Petrov’s parents decided they could not support a family of four, and enrolled him in a military academy.

Petrov studied long-distance radar systems and was stationed in the far east of Russia, where he met his wife, Raisa, who was working as a cinema operator at a military base in Kamchatka. He eventually retired from the military to care for her during her treatment for brain cancer. Reliant almost entirely on a state pension, he was reduced at one point to growing potatoes outside his apartment block to feed his family. For a time, he made soup by boiling water with a leather belt for flavour. His wife died in 1997. In addition to his son, Petrov is survived by a daughter, Yelena, and two grandchildren.

His story began attracting wide attention only in the late 1990s, after General Yury Votintsev, the retired Soviet missile-defence chief, published a memoir describing Petrov’s previously classified role in preventing a nuclear disaster. Until a Pravda journalist knocked on the door of the family’s apartment building, Peter Anthony said, Raisa Petrov had believed her husband was a pilot.

“Oh, your husband has saved the world from nuclear war,” the reporter said, leading Petrov to slam the door and, at least at first, tell his wife that the reporter had been lying. He was, Anthony said, “afraid that he was being tested”.

Stanislav Petrov, Soviet hero, born 7 September 1939, died 19 May 2017

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments