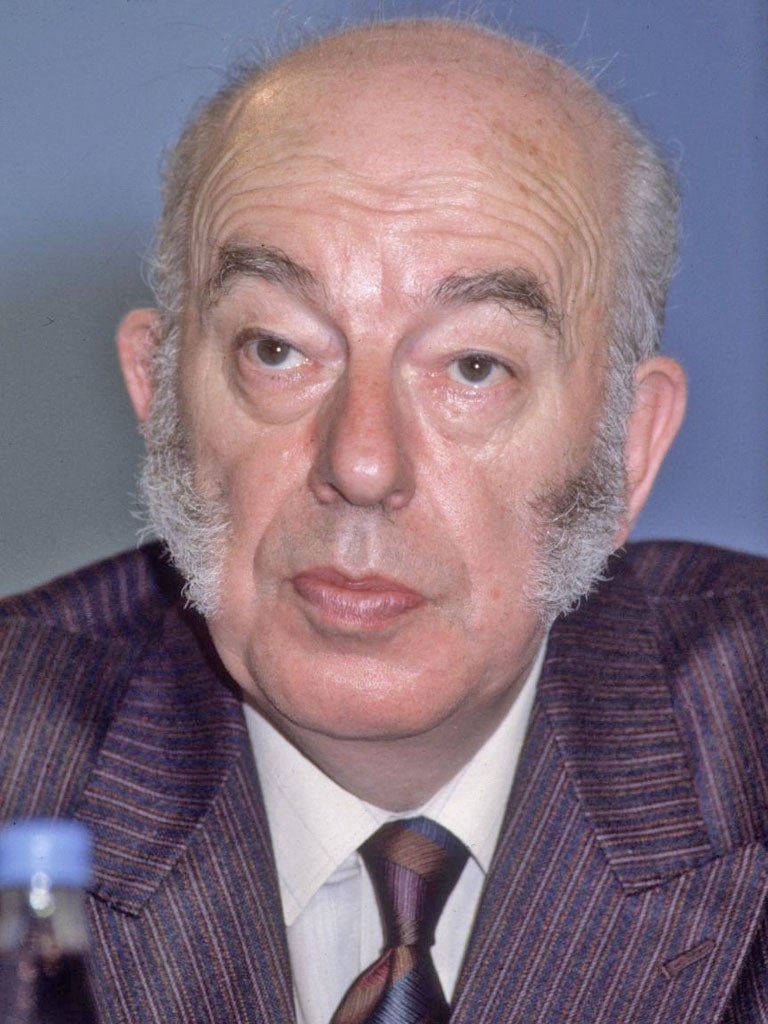

Sir Rhodes Boyson: Energetic MP whose embodiment of Tory values did not further his career

Rhodes Boyson was one of the most colourful Conservative MPs of his generation. Short, wiry, bald, but with mutton-chop sideboards, he was instantly recognisable. With his waistcoat, bow-tie and grating accent, he was like a mill owner in a Charles Dickens novel.

The impression was reinforced when he defended traditional values on abortion, hanging and homosexuality and attacked the permissive society. A skilful self-publicist, over time he became a prisoner of his own public image. Boyson was a go-getter and a man of diverse talents – as well as a head teacher, he was a publisher, author and politician.

Boyson was a Tory tribune, a populist and an authoritarian. Conservative toffs and grandees grimaced as he sounded off and the grass roots roared their approval. The accent, lack of shade in the views and the sheer cockiness of the man offended the grandees' sensibilities. In turn, he blamed them for his failure to reach the Cabinet.

Rhodes Boyson was formed by a strong working-class Labour household in the village of Rising Bridge, in East Lancashire. His father, William, was a remarkable self-made man, a pillar of the local Labour Party, a councillor, alderman and a trade union official. A a conscientious objector in the First World War, he uncomplainingly suffered ostracism in the local community. Boyson's parents were devout Methodists, thrifty and industrious. Between 1957 and 1961 Rhodes and his father both sat on the Labour benches in the Haslingden Council.

After service in the Royal Navy Rhodes studied politics and modern history at Manchester University and then qualified as a teacher. His early teaching experience was in Lancashire and was a Secondary head by 30. He moved to Stepney, to the headship of a tough school, then in 1967 was appointed head of Highbury Grove Grammar School as it was about to be merged with two non-selective schools to form a large comprehensive.

The headship gave him a status and platform to campaign for greater parental choice of schools, tests for teachers as well as pupils, and a core curriculum. He favoured traditional methods, including multiplication tables and grammar, and defended corporal punishment. He also contributed articles on education to the Daily Telegraph and the Spectator. His book Over-Subscribed: the story of Highbury Grove charted the school's success under his leadership. He also opposed neighbourhood comprehensives, spotting that they would introduce selection by house prices.

He had already gained his PhD, for a thesis on the 19th century Lancashire cotton industry. The study convinced him of the merits of the free market even before he became a Conservative. It also made him unsympathetic as an Education Minister to students who failed to complete their theses. By 1964, Boyson had grown disillusioned with Labour although it was another four years before joining the Tories. In 1969 he grew the famous sideboards, as part of a bet with his male students who, in turn, had to cut their long hair. The sideboards remained.

Boyson was also a prolific writer of argumentative, sometimes repetitive pamphlets and essays. He was a joint editor of the Black Papers series which attacked many of the progressive educational changes of the 1960s. He lashed the permissiveness of that decade, claiming that it elevated self-indulgence over duty and caused rises in crime, disorder, pornography, decline of patriotism and breakdown in family life.

All this brought him a high profile. Tory grassroots loved hearing his bold statements of what they thought privately. In the late 1970s he was second only to Margaret Thatcher in popularity as a speaker for constituency associations. A red rag to the liberal press, he claimed in his Who's Who entry that a hobby was "inciting the millenialistic Left in education and politics".

Colleagues were left in little doubt that the headship of Highbury Grove was not the summit of his ambitions. He became a Conservative councillor in 1968 for Waltham Forest, serving for six years, and the Conservative candidate for Eccles at the 1970 general election. He won selection for the new seat of Brent North, which he won at the February 1974 general election.

He had invented Boysonism before there was Thatcherism. In his book Centre Forward (1978) he produced what was effectively his own manifesto. This proposed lowering the top rate of income tax to 60 per cent, cutting public spending, privatising state utilities, ending exchange controls, increasing police numbers and pay and replacing much of the welfare state by vouchers. With the notable exception of vouchers virtually all the rest were delivered over the next decade. He also revived the Churchill Press, to publish texts arguing the case for the political right. His energy was remarkable.

When he entered the Commons in 1974 he was nearly 50, late for an ambitious politician, and his next five years were in opposition. Preferment came in 1976 when he was appointed deputy to Norman St John Stevas, the Shadow Minister at Education. He was happy with the party's platform of the parents' charter, providing greater parental choice. He was less happy with Stevas, whose irreverent wit, orotund sentences and mincing manner irritated him. When Stevas was moved in 1978 and replaced by another "wet", Mark Carlisle, Boyson voiced his disappointment that he did not get the post. He was never a natural No 2. He was ambitious and he and his friends saw him as a coming man.

In 1979 more disappointment followed when Thatcher formed her government; he was made an Under-Secretary with responsibility for higher education; it was claimed that appointing him minister for schools would alienate the teachers. He defended the cuts in university spending in 1980 and 1981, claiming that there were too many students in universities. Defending the imposition of full fees on overseas students, he noted that two-fifths came from Iran and Nigeria, adding "we do not seem to have gained much advantage from Iran, nor from Nigeria, who nationalised our oil without paying for it." In 1980 he piloted the Education Act through the Commons, a measure that introduced the assisted places scheme and extended parental choice.

When Sir Keith Joseph took over Education in 1981, Boyson was given schools. He thought this was a good opportunity to introduce school vouchers, a cause about which he was passionate. It was a means of curbing "loony left" councils and empowering parents. Sir Keith talked, studied and thought, but accepted the judgement of his officials that it was not practical. Boyson was furious. Indeed, he had difficult relations with officials in the department. He felt that he did not gain the support that he deserved from them in trying to save sixth forms, clip the wings of the Schools Council and save grammar schools.

Between 1976 and 1983, Boyson was confined to the education portfolio, and was a junior minister to three very wealthy, public school Oxbridge-educated man. He dismissed Stevas as lightweight; Carlisle was affable, a good listener and pragmatic about reform; Sir Keith was intense, intellectual and seemed to love argument more than a policy outcome. By contrast, Boyson cared passionately about change; he was populist, even simplistic. He was also the only one of the four who had had experience of state education as a pupil or as a teacher.

If education was a disappointment, more was to follow. The next four years saw him make sideways moves as a Minister of State at Social Security, Northern Ireland and Local Government. He was deeply frustrated at the promotion of those he regarded as his inferiors and not true Thatcherites, blaming the whips and William Whitelaw for his lack of promotion. The truth was that even Thatcher did not regard him as a good minister. He was quickly bored by detail, "winged" it, and was too quick to move into polemical mode. He also lacked smoothness. The self-confidence, radical views and forceful expression made him unpredictable. He was too much of a free spirit for the whips. Although, like Norman Tebbit, he was an unapologetic Thatcherite, his face did not seem to fit.

Boyson held his seat in 1987, but demotion for a 62-year-old junior minister was inevitable. The torch was passed to the younger and smoother John Moore and John Major. A knighthood did little to comfort him. On the backbenches he continued to speak out and write pamphlets on vouchers, workfare and reversing what he regarded as the country's moral decline. He made headlines when he suggested that pupils who failed tests at seven, 11 and 14 should spend their summer holidays in the classroom. In one pamphlet, The Need for Limited Government, he advocated compulsory military service. He seemed profoundly ill at ease with modern Britain. But he was also a crusading optimist, believing that turning the clock back would make people happier. One of only two Conservative Methodists in the House at the time, he chaired the All-Party Methodist Group.

He could still spot potential political disasters. He warned that the poll tax would be "a Labour Party benevolent fund", and as a Eurosceptic he opposed steps to greater European integration and attacked the effects of Britain's membership of the ERM. Journalists found him ever-ready for a quote, which often distinguished his own views from the government's.

Boyson lost his seat in the 1997 Labour landslide. He wrongly thought that he had a large personal vote garnered over 23 years. The 18 per cent swing came as a severe shock. There was no elevation to the Lords to comfort him and provide a platform. Friends looked in vain for a big book but he had spent his best years away from his desk. He published a sort of autobiography, Speaking My Mind, in 1995. Apart from the early chapters, which evoke movingly his early life it contained too much "Boysonism", views on how to set the world to rights, and too many speech extracts.

For all his restless energy and desire for a public audience, Boyson cherished family life. His own parents made a profound impression on him and he was devoted to his father. He was also proud of two daughters from his first marriage. His second was to Florette, whom he met while she was on the staff of his school.

Dennis Kavanagh

Rhodes Boyson, teacher and politician: born Rising Bridge, Lancashire 11 May 1925; MP for Brent North 1974–1997; Opposition spokesman on education 1976–79; Under-Secretary of State, DES 1979–83; Minister of State: for Social Security 1983–84, Northern Ireland 1984–86, Local Government 1986–87; Kt 1987; married 1946 Violet Burletson (marriage dissolved; two daughters), 1971 Florette MacFarlane; died 28 August 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments