Sir Peter Heatly: Diver who won Commonwealth medals before becoming an admired sports executive

He was largely responsible for persuading Commonwealth countries to return to Edinburgh for the 1986 Games

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

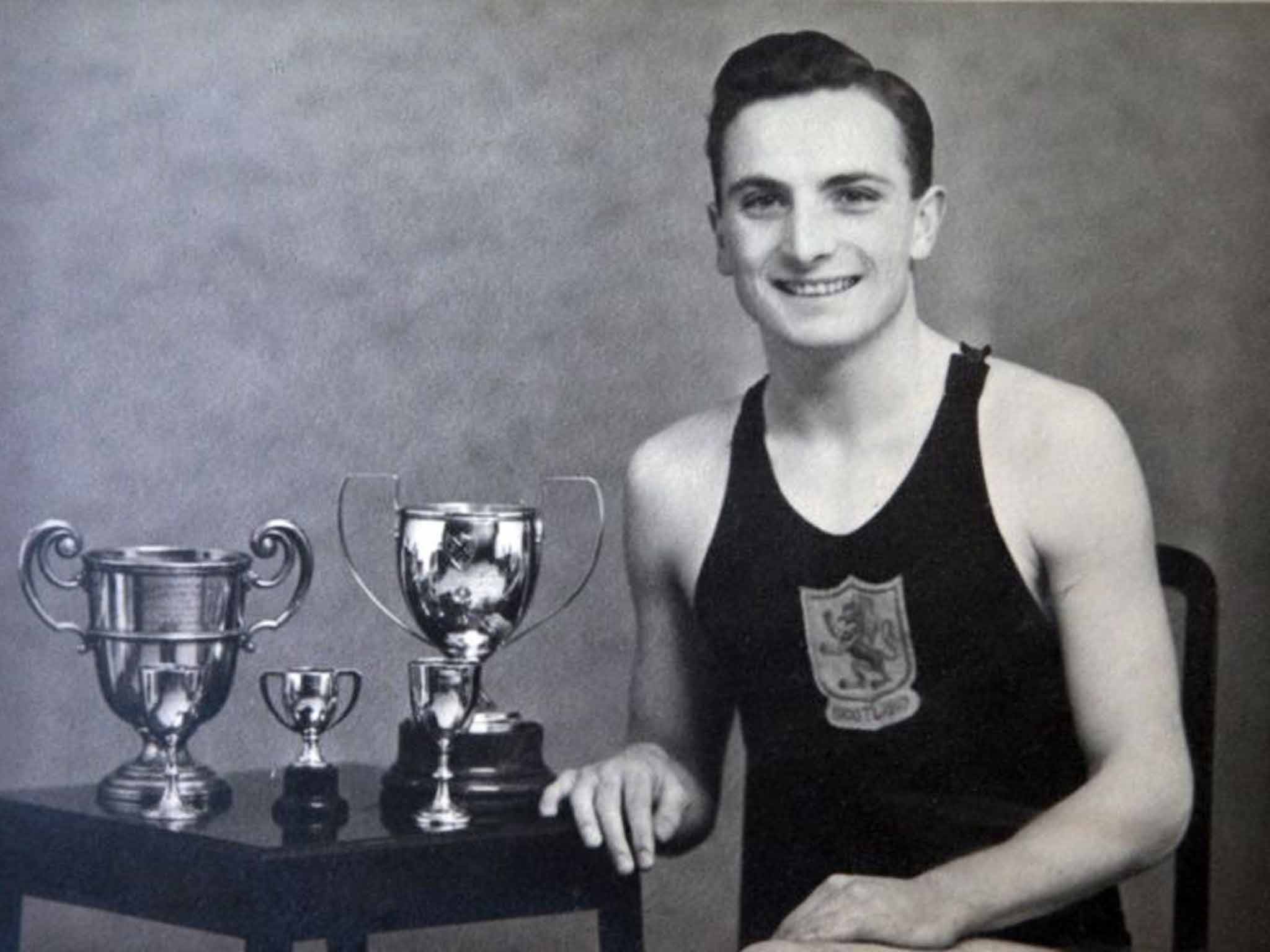

Your support makes all the difference.It is difficult to convey nearly 70 years later the thrill for us teenagers growing up in the Lothians that one of our own, a Leith Academy boy and Edinburgh University engineering student, should go to the 1948 Olympic Games and prove himself to be a world-class diver. Peter Heatly, ever modest, and immaculately turned out, was, quite simply, the best kind of role model. Squat and muscular, he had a natural dignity which commanded the attention of the many different sporting and engineering personalities with whom he had dealings.

Born into a family that built up a small heating and plumbing firm in the port of Leith, Heatly was taken by his mother to the then state-of-the-art Portobello Open Air Pool, and after a second visit asked to join the swimming club there – he told me he was excited by the divers, "belly-floppers and all". Endowed with natural gymnastic talent and a vast reservoir of raw courage, by the age of 16 Heatly was Eastern Area of Scotland diving champion, an honour he held until the outbreak of war.

As a promising civil engineering undergraduate at the University of Edinburgh, Heatly was directed to the reserved occupation of apprentice at the Naval Dockyard at Rosyth. Fortunately the excellent sports facilities there enabled him to sustain regular training. But when Heatly won his first Scottish Championship, in 1946, and went to the Olympic Games in London in 1948, he was largely self-coached. Not exactly enviously, but with a tinge of melancholy, Heatly reflected over a cup of tea in my house, "I would like to have had, three-quarters of a century ago, what Tom Daley has now!"

At the Olympic Pool Heatly finished out of the medals in a competition featuring the 3 metre springboard and 10 metre high board and dominated by the formidable Americans of the day. Heatly recalled that mixing with Fanny Blankers-Koen and other Olympic giants whetted his lifelong appetite for international sport, to which he was to devote his life.

In 1950 in Auckland Heatly won Commonwealth gold in the 10 metre event and silver in the springboard behind his friend, George Athans, father of the Olympic skier Gary. Heatly loved being a member of his "generous to one another" camaraderie of divers.

Medals at the 1952 Olympics eluded Heatly, faced by competitors who enjoyed the fantastic facilities of California and Florida. But a second Commonwealth gold came in 1954 in Vancouver, in the springboard, and before retiring in 1958 he won his hat-trick Commonwealth gold in Cardiff in the highboard.

Not only did Heatly, who believed in "giving something back to the sport", move effortlessly into sports administration, unremunerated, but he organised himself so well that he could build up his own engineering business. It was as a member of the organising committee of the 1970 Commonwealth Games – the so-called "Friendly Games" – in Edinburgh that I came to know Heatly well, in his capacity as a prominent member of the Scottish Sports Council, of which he was to become chairman in 1975.

Much of the preparatory work had been done by the Labour Sports Minister Denis Howell, but when the Wilson government was ousted at the general election, weeks before the Games, all the hotel rooms booked for Howell were automatically transferred to his Conservative successor as Sports Minister, Eldon Griffiths. I know that in Howell's opinion, Heatly was a crucial factor in bringing the 1970 Games to Edinburgh in the first place, and in getting government support for the City Council's construction of the Olympic-sized Royal Commonwealth Pool and its diving facilities.

I admired Heatly for something else: he did not simply champion swimming and diving. Our organising committee chairman, the decent – but financially anxious rate-payer – Lord Provost of Edinburgh, Sir Herbert Brechin, was minded to give in to powerful figures in the world of athletics, who thought that the velodrome would be too expensive and should be scrapped. Politely but firmly, Heatly told him, in my presence, "Lord Provost, you cannot renege on your promises to the cyclists! If you do, you would be breaking the conditions on which Edinburgh was awarded the Games."

Heatly prevailed. No Heatly, no velodrome. And – no exaggeration – no velodrome, no Sir Chris Hoy.

From 1982 until 1990 Heatly was Chairman of the Commonwealth Games Federation. I am told that Federation members hugely admired the charming skill and "pawky" sense of humour with which he managed to contain certain loquacious colleagues with a tendency to ramble on.

Heatly was largely responsible for persuading Commonwealth countries to return to Edinburgh for the 1986 Games. Though there were financial problems, all seemed set to emulate the successes of 1970 – until Margaret Thatcher took a stand opposing sanctions against apartheid South Africa. Country after country decided to boycott the Games and organisers were facing a financial black hole.

Enter Robert Maxwell, promising money (never delivered). At the opening ceremony he insisted on sharing the dais, which resembled a boxing ring, with the Queen, who was to open the Games. We were aghast, all 20,000 of us, as inch by inch, Maxwell's ample behind pushed this relatively little lady to the edge of the podium. It was the only time I ever saw the unflappable Heatly seethe with indignation.

Years later, he told me: "When we realised what Mrs Thatcher had done, just 10 days before the Games were due to open, we would wake up every morning and find that another country had decided not to come. The boycott was terrible: you died a little bit every day."

Since no other city had bid, it was to Heatly's eternal credit that the Games took place at all. Six years earlier he had been a stalwart friend to Charlie Palmer of the British Olympic Association in defying Thatcher, who wanted Britain to boycott the Moscow Olympics following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

For more than 60 years, Peter Heatly was an active Rotarian and a discriminating giver to charities, mostly those supporting young people.

Peter Heatly, diver, engineer and sports administrator: born Edinburgh 9 June 1924; CBE 1971; Kt 1990; married 1948 Jean Hermiston (died 1979; two daughters, two sons), 1984 Mae Calder Cochrane (died 2003); died Edinburgh 17 September 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments