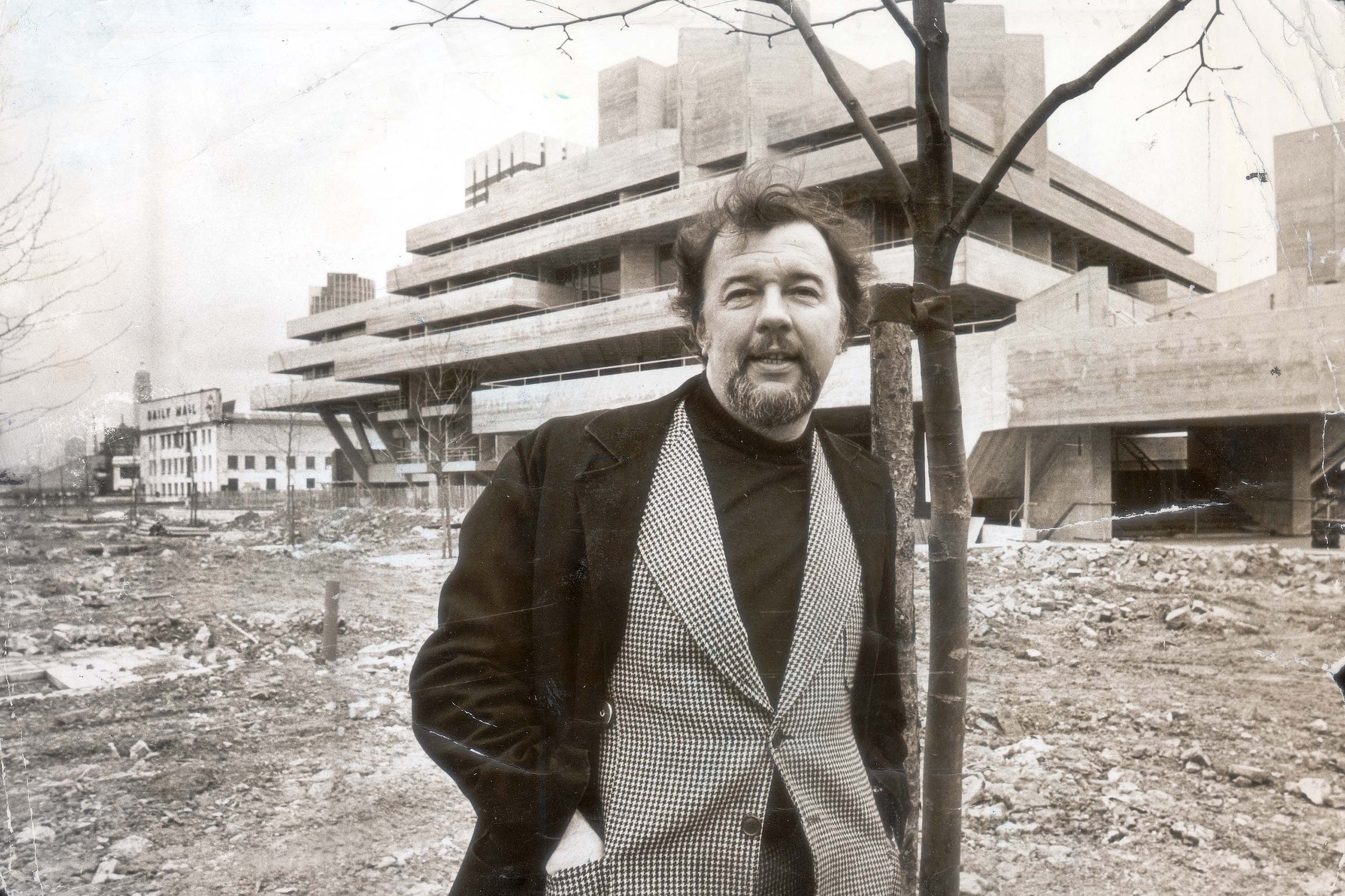

Sir Peter Hall, titan of British theatre

Founder of the RSC and director at the National Theatre for 15 years, Hall could rightly say that his whole life had been spent ‘trying to understand the power’ of the art to which he was devoted

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Amidst the fuss surrounding the 1972 appointment of Peter Hall as successor to the National Theatre’s first director, Laurence Olivier, the National’s literary manager Kenneth Tynan said of Hall, who had been the main architect in creating the Royal Shakespeare Company: “We are the Cavaliers, Stratford the Roundheads – with the emphasis on analytical intelligence and textual clarity. Under Peter Hall the country would have two Roundhead theatres.’’

Tynan’s theory was alarmist tosh – Hall was much too canny simply to replicate the RSC on the South Bank – but Hall would not have demurred at the “Roundhead’’ comparison; without conventional religion, his roots nevertheless lay in the nonconformist Suffolk soil of his childhood (he once labelled himself “an East Anglian Puritan’’), the radical instincts nurtured by his station-master father and in his Cambridge education as a scholarship boy at the Perse School and St Catharine’s College where his lucid intelligence was honed by the teaching of that arch-Roundhead FR Leavis, who gave the adolescent Hall something of his conviction that the moral weight of art might surpass that of religion.

A central paradox about Hall, however, was the co-existence in his nature of a strong Cavalier streak. Despite outward composure he could be impulsive and strongly, even violently, emotional – he suffered acute nervous breakdowns at crucial points in his career – while much of his work, especially during his earlier Stratford period, was highly romantic in approach and design. The combination made for a redoubtable personality, as much resented as loved (detractors’ nicknames included Genghis Khan and Tammany Hall).

Nobody who is impresario and director can survive without a ruthless streak (Olivier had one) and Hall undoubtedly made many enemies. He took over RSC productions and could abruptly fire actors – Zia Mohyeddin days before opening as Romeo at Stratford or, having wooed her heavily (‘’Peter Hall gives good phone,’’ she said later), Sarah Miles from a 1997 Cvmbeline. While his NT reign made lasting opponents of directors Michael Blakemore and Jonathan Miller.

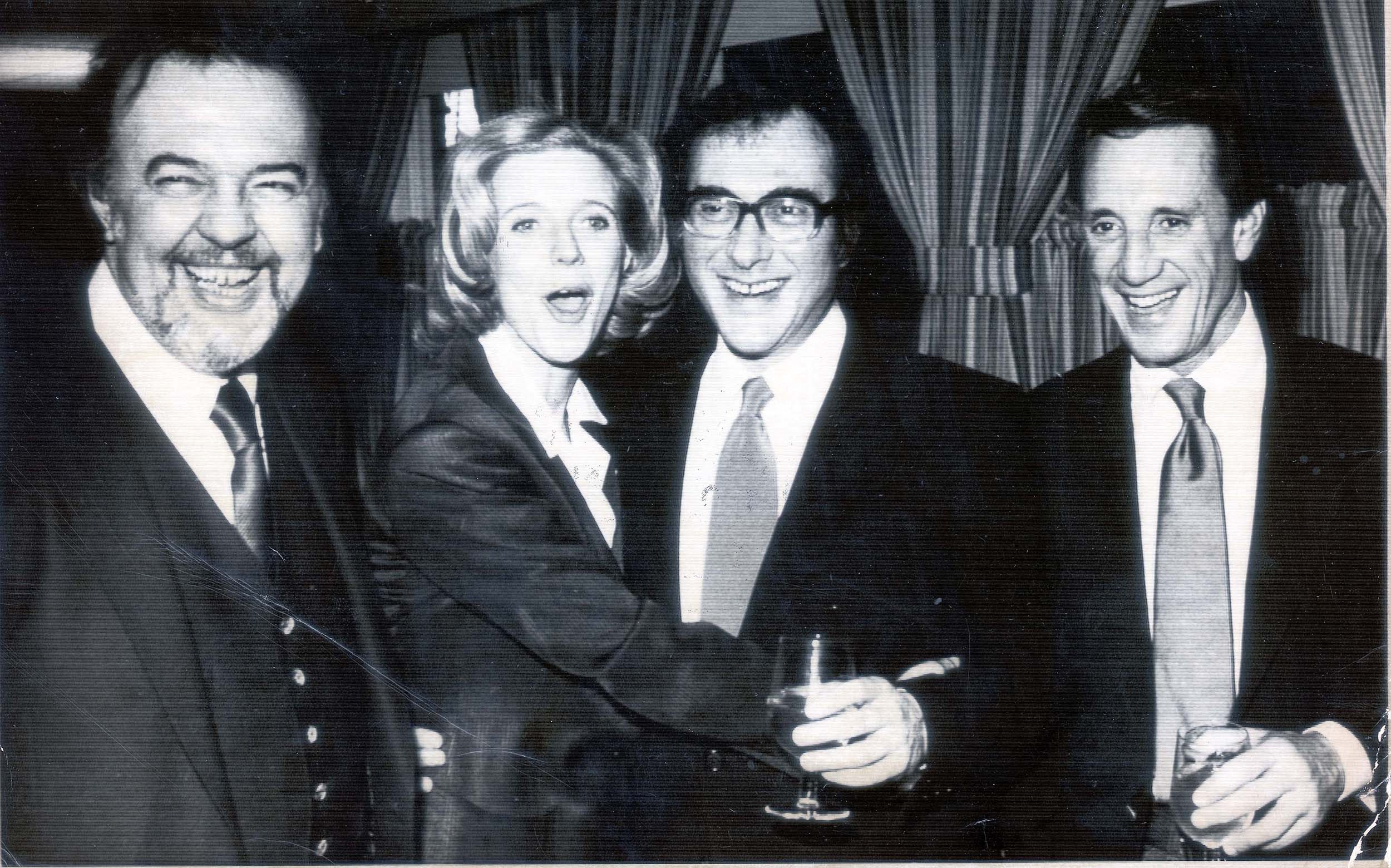

Yet it is equally true that Hall forged enduring partnerships with some of the most significant artists of his era – Peggy Ashcroft, Judi Dench, Dorothy Tutin, Janet Baker, John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson, Georg Solti among them. Perhaps only someone with Hall’s particular mix of acute sensibility and ambition, fused to silky operating skills (his French first wife was reminded of Cardinal Richelieu) could have become, as well as a top-flight international director in opera and theatre, unquestionably the UK’s great impresario of subsidised theatre in his era.

From childhood Hall’s direction seemed clear to him. There was no theatrical tradition in his genes, although both his parents were music lovers and encouraged their only child’s musical instincts by taking him to Mozart concerts (Shakespeare and Mozart would always be his main loves).

The Perse School had strong theatrical traditions – Hall played a teenage Hamlet there – with masters who encouraged both his theatregoing and his path to St. Catharine’s after his National Service in the RAF.

Hall’s was an outstanding Cambridge generation – writers included Frederic Raphael (later to give an acid-tinged portrait of Hall in The Glittering Prizes) and Thom Gunn and other theatre-enthusiasts were John Barton, Raymond Leppard and Peter Wood, who would become professional colleagues. Hall was comparatively quiet until late in his undergraduate career when his productions of John Whiting’s Saint’s Day and Love’s Labour’s Lost (he mined a profitable vein of sexual frustration in the latter) made him a Cambridge star.

Young directors need luck as well as talent and Hall had some enviable breaks. The director of London’s Arts Theatre, Alec Clunes, faced with a gap in programming, brought in a filler of a Cambridge production of Pirandello’s Henry IV, directed by Hall. Clunes recommended Hall to John Counsell of Windsor’s Theatre Royal, who invited him to make his professional debut there with Somerset Maugham’s The Letter (1953). Counsell offered Hall the job of resident director and was not a little put out when Hall refused, going instead to the Oxford and Cambridge Players, a touring group involving John Barton for whom he directed an impressive Twelfth Night (1953).

When Clunes left the Arts he recommended Hall to his successor John Fernald for whom Hall directed Blood Wedding (1954); Lorca was unfamiliar in London then and Hall’s sensual production was favourably noticed. And then Fernald was appointed principal of Rada, leaving the Arts position unexpectedly vacant, filled by a 24 year-old Hall.

His production of The Impresario of Smyrna (Arts, 1954) was a thudding flop – Goldoni and Hall were not natural bedfellows – and made him feel his luck had run out, but over the next year, programming new and sometimes controversial European work, Hall continued to announce himself as a fast-track talent, his productions including, most memorably, the British premiere of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (Arts and Criterion, 1955).

As potent in its impact on the British stage as anything from the Royal Court’s Look Back in Anger-led “revolution’’ beginning the following year, Beckett’s play was another serendipitous stroke for Hall. Having begun by emphasising the clown-like aspects of Vladimir and Estragon, gradually the humanity of the characters began to seep through, leading Hall to stress – as he did when returning later to this personal favourite – the characters’ affinities with tramps.

Godot made Hall a hot property. On the gossamer West End version of Colette’s Gigi (New, 1956) he fell in love with its star Leslie Caron, then a major movie name; their marriage and snazzy lifestyle made them a fashionable London couple. Stratford’s Memorial Theatre Company also wanted Hall; his debut there was an uncharacteristically artificial Love’s Labour’s Lost (1954) with a romantic James Bailey design.

Hall returned to Stratford for Cymbeline (1957) with Peggy Ashcroft as Imogen in another highly atmospheric production, designed by the genius of the romantic verismo tradition, Lila de Nobili. He also made his first excursion into opera with John Gardner’s The Moon and Sixpence (Sadler’s Wells, 1957). The piece is forgotten, but Hall’s work was lavishly praised, not least for the unusual conviction of its acting.

When he directed John Mortimer’s Wrong Side of the Park (Cambridge, 1959) it was Hall’s last work in the commercial theatre for more than a decade. For Glen Byam Shaw’s farewell Stratford season Hall was walking with giants, directing A Midsummer Night’s Dream with Charles Laughton’s Bottom in de Nobili’s magical Elizabethan country-house setting and Olivier and Edith Evans in Coriolanus. Wisely he allowed Olivier some of his “special effects”, most awesomely his gravity-defying death leap, but it was possibly on that production that Hall began his move away from soft-focus romanticism; Coriolanus’s permanent set was by the great Broadway veteran Boris Aronson. The Stratford powers were likewise contemplating change and Byam Shaw’s suggestion of Hall as his successor was accepted by a board headed by Sir Fordham Flower (“Fordie”), who became a supportive surrogate-father figure.

Hall had already articulated something of his ideal of a permanent company, less star-dominated (although the first actor he approached was Peggy Ashcroft). And he impressed everyone during his first season (1960) as he coped with some nasty crises. Rex Harrison then Paul Scofield withdrew from agreeing to join the Stratford company but Hall replaced them with the young Peter O’Toole, whose charisma dominated the season; then he had to deal with a crisis on Taming of the Shrew, taking over from John Barton to assuage a jittery Ashcroft. Hall’s own new work that season – Troilus and Cressida – was a revelation, one of the iconic productions of its era in Leslie Hurry’s sandpit set backed by a vast cyclorama with a signally erotic Cressita from Dorothy Tutin. The production also reinforced that under Hall Stratford would maintain verse-speaking standards. (Barton was enormously helpful in this regard.)

There were disasters in Hall’s early days, including the Zeffirelli/Gielgud Othello (1961), cursed by a first night which saw Murphy’s Law soar into overtime as the director/designer’s Veronese-inspired sets took aeons to change. That season was rescued only by the success of As You Like It (although its director, Michael Elliot, was never invited back) with the glorious Rosalind of Vanessa Redgrave, with whom Hall was having an affair (somewhat to the chagrin of rival suitor Michael Blakemore, then a Stratford actor, who later drew another of the jaundiced fictional portraits of Hall in his novel Next Season).

But Hall was on a roll after persuading Fordie of his plans for a company and a London base thst would also tackle new work, and a newly named Royal Shakespeare Company had its first London season in 1960 (including John Whiting’s The Devils and Hall’s shimmering production of Ondine with Caron a seductive water nymph) at the Aldwych, its home in the capital until the opening of the Barbican Centre.

Before long, Hall had expanded into his old Arts Theatre for an ambitious season of mainly new work including the revelation of David Rudkin’s Afore Night Come (1962) at the same time as his first Pinter production with The Collection (Aldwych, 1962). As British society seemed to undergo seismic change, the RSC echoed the pace as Hall stamped the organisation with a strong radical identity.

There would be no more designs from de Nobili or Hurry; fired by the work he had seen at the other Stratford (London E15) from a trail-blazing designer, John Bury, and also under Brecht’s increasing influence in England, Hall now sought out something rougher and Bury was the chosen man (“Go home, you fucking cement-mixer,” yelled the sartorially impeccable Hurry to the boiler-suited Bury at the Stratford stage door) who would design the Hall productions which more than any others forged the RSC’s aesthetic, the 1963 history cycle of The Wars of the Roses.

Partly a nod to Stratford’s past and the legendary Festival of Britain cycle, the venture was also a gauntlet for the future in its revisionist view of history and the pervasive corruption of power. In Bury’s mould-breaking sets of wood and steel, the enterprise was as rich in detail as in overall sweep; conceived before Jan Kott’s seminal Shakespeare Our Contemporary was published, the production was remarkable for its unforced contemporary parallels with European totalitarianism. The acting – ranging from Ashcroft’s tour de force as Margaret developed from youthful innocence to aged virago, through mighty performances from such committed actors as Donald Sinden and Brewster Mason, to the discovery of David Warner’s holy fool Henry VI – revealed a genuine ensemble of world-class stature.

The strains of the venture and his disintegrating marriage resulted in Hall’s breakdown, repeated the following year when all the history plays were scheduled, finally directed by a collective headed by Hall including Barton and Peter Wood. There were those – most vocally Hugh Griffith, who did not return to repeat his Falstaff – who asserted that Hall’s collapses were due to his power mania. That charge, however, overlooks Hall’s championing of other directors and his unswerving support for Peter Brook as Peter Weiss’s Marat/Sade (1964), involving Hall often in arguments with the Lord Chamberlain’s Office or in public defence of Brook.

Another annus mirabilis for Hall was 1965, which saw his exploration of Pinterland in The Homecoming (Aldwych, 1965), an athletic and sexy production, meticulously attentive to the text’s ellipses and rhythms. He also directed a startling Hamlet (Stratford and Aldwych, 1965) with David Warner’s spotty and stooping student Prince less a “tragic’’ interpretation than one mining a disillusion so profound that commitment, whether to life or politics, becomes unbearable, a portrayal deeply resonant for contemporary younger audiences.

That year also marked Hall’s return to opera, lured by David Webster at the Opera House for the British premiere of Schoenberg’s Moses and Aaron under Solti’s baton. It was the perfect Hall piece for that time – large-scale and technically demanding with a climactic orgy scene involving naked chorus members and an entire menagerie of animals. It was during the dress rehearsal of this scene, with percussion and brass blaring, nude dancers (boosted by six enthusiastic Soho strippers) whirling in frenzy and blood coursing through stage troughs that a nervy camel took fright on the raked stage and charged, defecating copiously, towards the footlights while cast and orchestra fled for cover, allowing Hall to turn to his assistant to deliver an order given to few directors outside possibly the world of Hollywood epics at their most excessive to utter: “Cut the camel.”

Moses and Aaron had the world’s opera houses bidding for Hall but he chose to stay in London to work with Solti on The Magic Flute (ROH, 1966) and mount The Knot Garden (ROH, 1970) by Michael Tippett, in whose mystic humanism Hall found parallels with Shakespeare’s late romances.

Later RSC work included further collaborations with Pinter, including Landscape and Silence (Aldwych 1969) with an incandescent Ashcroft and the erotic triangle of Old Times (Aldwych, 1971), its trio of Tutin, Vivien Merchant and Colin Blakely unerringly steered by Hall. But other RSC ventures were more unsettling – a disastrous Macbeth (Stratford, 1967) with Scofield and Merchant both pallid, a weak “star-vehicle’’ comedy – Staircase by Charles Dyer (Aldwych, 1966) – with Scofield as a wildly camp hairdresser (‘’God help us all and Oscar Wilde!’’) and two decidedly over-reverent productions of Edward Albee missing much of their comedy, in A Delicate Balance (Aldwych, 1970) and All Over (Aldwych, 1972) with Ashcroft and Angela Lansbury. All were impeccably mounted but curiously soulless. With a new marriage (to his former assistant Jackie Taylor) and following Fordie’s death, it was time to leave the company he had so crucially helped to create.

Hall’s post-RSC life promised a concentration on music. He had made his Glyndebourne debut with the reclamation of a forgotten masterwork of the Baroque, Cavalli’s La Calisto (1970) with Janet Baker as a lustrous goddess Diana. Now he returned for another revelatory collaboration on Monteverdi’s II ritorno d’Ulisse (1972) with Bury recreating the Baroque tradition of moving skies and oceans but poles apart in execution from the painterly Glyndebourne tradition.

The shrewd ROH chairman Lord Drogheda brought Hall together with Colin Davis, soon to succeed Solti as music director; such was their rapport that Hall agreed to become director of productions alongside Davis. Both his Covent Garden productions at that time – a tremulous Eugene Onegin and Tristan and Isolde (both 1971), the latter provoking furious attacks on Hall’s gory handling of Tristan’s death – promised fair.

Then, as Hall put it with some circumspection, he “behaved rather badly’’ and backed out of the ROH job, not long before his National Theatre appointment was announced. Hall always claimed that he did not know that Max Rayne, chairman of the NT board, with that consummate Mr Fixit, Lord Goodman, had lined him up in advance, but others – not least John Tooley, the ROH administrator – remained convinced that Hall knew he was going to the South Bank before he jumped ship at Covent Garden.

Whatever the truth, Hall inherited something of a poisoned chalice. For once, his timing was off; he took over the NT just as the country began a slide into recession and he faced not only some tricky Olivier behaviour but also nightmare delays on the new building.

Hall fought fiercely at the NT – he described his initial time there as “a war that had to be won” – battling with builders (the new building only opened – in stages – in 1976), a hostile Evening Standard, a series of arts ministers even more inept than usual and – most exhaustingly – potentially ruinous extremist-led industrial action. It was difficult for a man of Hall’s generation and ideals, appalled by the disintegration of a once-independent body like the Arts Council into a limp arm of government staffed by dim apparatchiks, not to fight the subsidised corner. His most memorable battle resulted in “the coffee-table speech” at the NT when he stood on a low table to address journalists on subsidy cuts (Mrs Thatcher reputedly demanded of the hapless arts minister Richard Luce: “When will we be able to stop giving money to awful people like Peter Hall?”).

Hall also brought contemporary writers into the building – David Hare, Alan Ayckbourn, Edward Bond, David Mamet and Stephen Poliakoff – while wooing Pinter, Albee and Shaffer to the NT. He was generous to the work of Bill Bryden and his regular team of actors (The Mysteries in Tony Harrison’s version was particularly fine) and brought in his eventual successor Richard Eyre for a blockbuster Guys and Dolls.

Hall’s ambition was to provide the operation with an identifiable aesthetic, but in this he cannot be said to have succeeded, not least because of the effective abandonment of the ensemble ideal. Also his own productions at the NT varied astonishingly in quality.

Surprisingly he rarely struck form in Shakespeare; only near the end of his regime, with a stirring Coriolanus with Ian McKellen and an Antony and Cleopatra (1987) of superbly confident sweep, and a magnetic Cleopatra out of a self-described “menopausal dwarf” (Judi Dench) did he come up with anything comparable to his RSC glories. He buried Gielgud’s last stage Prospero in The Tempest (1973) under fussy elaborations borrowed from Glyndebourne’s Baroque experiments and seemingly bored even Albert Finney in the title role of a Hamlet (1975) of surpassing greyness in design and direction, while Macbeth (1975) with the potentially rich casting of Finney and Tutin and Othello (1980) with Scofield were stately, bland and dull. He owned himself in his published Diaries that his attempt to find “a new classicism’’ in Shakespeare had failed.

Equally unsatisfactory was his South Bank attempt to launch a Broadway musical, a genre Hall never understood (possibly because he fundamentally despised it), with Jean Seberg (1983), exploiting the star’s life for some limp satire with a disappointing Marvin Hamlisch score. Hall’s denials that the show was using a subsidised theatre as a Broadway try-out were less than convincing (in the event its failure ruled out New York hopes).

Yet Hall had his NT triumphs, including the enormous success of Shaffer’s Amadeus (1979) with Scofield as Salieri, Pinter’s No Man’s Land (1975) with Gielgud and Richardson’s incomparable double-act and the magnificent epic undertaking of the Oresteia trilogy (1981), muscularly translated by Tony Harrison with Jocelyn Herbert contributing to another of the iconic productions of the later 20th century theatre with her Epidaurus-influenced set and using masks for the all-male cast. The latter proved an inspiration once the company realised that masks do not obscure but reveal.

His NT valedictory was the trio of Shakespeare’s late romances – The Tempest, Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale (1988) – which were strongly cast (Michael Bryant a Prospero of rare passion) but never quite fully mined the cruelties in these apparently benevolently solved fairy stories.

Always seemingly pressed for money despite his earnings – he had more responsibilities for children when his second marriage ended prior to his third, to singer Maria Ewing – Hall’s outside work, inevitably causing frictions with colleagues during some absences, included during his NT years TV’s Aquarius, more opera and films.

Although attracted to the on-set world of film-making, like most British stage directors of his time Hall’s sensibility never adjusted happily to the screen. His movies began with a mangling of Henry Livings’s surreally airy RSC comedy Eh? as Work is a Four-Letter Word (1968) with David Warner a supposedly Keatonesque anti-hero and the celebrity casting of Cilla Black, and covered several serviceable records of stage productions such as The Homecoming (1969) alongside an intense and intensely dull triangle-drama scripted by Edna O’Brien, Three Into Two Won’t Go (1969) with Rod Steiger at his least subtle. The best of his screen excursions was his loving recreation of pre-war Suffolk rural life taken from Ronald Blythe’s Akenfield (1974), mostly improvised with an amateur cast, marred only by some tumbles into the trap of the Laura Ashley School of Period Films.

Glyndebourne continued to see Hall’s best work as he tackled Britten with A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1981), a glorious production (still deservedly in the repertoire in Bury’s recreated Arthur Rackham-inspired designs) and Verdi with a rueful, autumnal Falstaff (1983).

Elsewhere he sometimes had less luck; his Bayreuth Ring Cycle (1983) suffered from obviously inadequate preparation and was not well received, while a bizarre Macbeth (Metropolitan Opera, NY, 1982), like some 19th century melodrama with flying witches, was trounced by press and public. More successful were his collaborations with Maria Ewing on a vibrant Carmen (Glyndebourne, 1985) and Strauss’s Salome (Los Angeles, 1988), a thrilling production in a Bury set like a Klimt nightmare.

In 1988, Hall formed what was known for more than 20 years as the Peter Hall Company. Although some loyal actors appeared in several productions, in truth it was essentially star-led with most shows cast separately, revealing little of any genuine ensemble ethic. It also had no permanent home; Hall initially hoped to be housed at the Haymarket with Ayckbourn joining him but that arrangement was short-lived, surviving only Williams’s Orpheus Descending (Haymarket 1988 and NY, 1989) with Vanessa Redgrave a mesmerising Lady Torrance.

Other houses included, briefly, Chichester (for a dire musical, Born Again, based on Ionesco’s Rhinoceros, which nearly bankrupted the place in 1990) and, also briefly, the Playhouse, the highlight of which was Julie Walters’s life-force Rosa in The Rose Tattoo (1991) and a short period at the Old Vic (1997).

Impresarios were beginning to discover that few people got rich with the PH Company other than the stars and Hall himself (instead of royalties he now often insisted on large up-front fees, a lucrative deal for a limited run). His next producer, Bill Kenwright, lost a considerable sum on their first venture, an impenetrable Poliakoff piece, Siena Red (Liverpool, 1992), which closed out of London.

After a brief return to the RSC, Hall under Kenwright directed a rickety Separate Tables (Albery, 1993) and a broad, even strident, version of She Stoops to Conquer (Queen’s, 1993). The sense of a conveyor-belt rather than of a series of plays produced out of Hall’s real passion became increasingly hard to escape. Occasionally there were gems – An Ideal Husband (Haymarket, 1998) was a truly major production (revived several times with various casts) on which Hall infused Wilde’s society drama with sharp insight and genuine feeling, yet a subsequent Wilde, Lady Windermere’s Fan (Haymarket 2001), despite a starry cast, was barely perfunctory.

Hall directed a Piaf revival (Piccadilly, 1993) as an unabashed star vehicle; it was hard to reconcile the architect of 1960s ensemble-theatre with the director instructing his “company” to surround and applaud Piaf’s star (Elaine Paige) at her solo call; it called into question his patronising dismissal of A Chorus Line’s “showbiz values’’ (its final number is an ironic take on what Hall staged literally for Piafs curtain calls).

He was on surer form with Feydeau, co-translating Le Dindon as the bravely titled An Absolute Turkey (Globe, 1994) with his fourth wife Nicki Frei, although a following Feydeau, Mind Millie for Me (Haymarket, 1996) was a mirth-free disaster zone. A return to Shakespeare with Hamlet (Gielgud, 1994) was a patchy affair with little of the visceral excitement of his 1965 version, most notable for Donald Sinden’s consummate study of Polonius as elder statesman.

Back with Kenwright for a season at the Piccadilly (1998) Hall had Judi Dench as de Fillipo’s eponymous ex-whore, in a performance of naked emotional truth, to thank for the success of Filumena; both The Misanthrope and Kafka’s Dick by Alan Bennett were, again, blandly efficient with little genuine amperage to power them.

Work away from the PH Company included opera – most strikingly a darkly brooding Otello (Chicago, 2001) – and yet more revivals including Amadeus (Old Vic and USA, 1998) and a leaden production of the Kaufman/Ferber valentine to Broadway The Royal Family (Haymarket, 2001) in which even Dench failed to shine. As with a plodding Whose Life is it Anyway? (Comedy, 2005) with the bait of Kim Cattrall’s casting, it was difficult to see what, fees apart, attracted Hall to such projects.

Reminiscent of better days, if not on the Oresteia level, was his Greek-drama marathon, Tantalus (Denver, 2000 & Barbican, 2001) reuniting him (less than happily as it transpired) with John Barton and a return to Beckett and the Arts Theatre for a robust Happy Days (2003) with Felicity Kendal.

The latest backer of the PH Company became the Theatre Royal, Bath where from 2003 Hall usually presented an annual season, early productions including an astute pairing of amatory-triangle plays with Pinter’s Betrayal and Coward’s Design for Living (2003) and a 2004 As You Like It which then played the Rose Theatre, Kingston which Hall hoped would be his future home.

Bath saw the third Hall scrutiny of Godot (2005), as precisely scored as his 1997 Old Vic version, alongside a lacklustre You Never Can Tell (which transferred to the Garrick, 2005) while his 2006 season drew some of the poorest notices of his career (“bathchair Shakespeare” was one verdict on Measure for Measure, while he failed to find the comedic mainspring of Bennett’s Habeas Corpus). A 50th anniversary production of Godot, as always fusing comedy and heart-stopping pathos, and transferred to London (New Ambassador’s, 2006).

Hall also had that year a commercial smash hit with (as a freelance for Kenwright) Coward’s Hay Fever (Haymarket, 2006). It had some of the heaviness sometimes afflicting Hall’s comedy – a crucial running sight-gag was completely muffed, surprising for a director so insistent on the observance of text – but Dench was in irrepressible form as the actress-diva at the centre of Coward’s gorgeous frivol – The Apple Cart (Bath, 2009) was a refreshing taste of vintage Hall. And while a return to Ayckbourn’s Bedroom Farce (Kingtson and Duke of York’s, 2010) was sadly uninspired, his revival of Twelfth Night at the National in 2011, with his daughter Rebecca playing Viola, was a bittersweet swansong.

Despite the uneven quality of so many later productions – his outsize appetite for work undeniably led him often to take on too much – there is no doubting Hall’s sincerity in describing his love of rehearsals (‘’almost an erotic passion’’ as well as the habit of a lifetime) or in asserting: “My entire working life has been spent trying to understand the power of theatre.” The British theatre owes a considerable debt to that devotion. For Hall, as for his friend and colleague John Gielgud, the theatre was more than an occupation or a profession; if for different reasons, it was for him too a life.

Sir Peter Hall, born 22 November 1930, died 11 September 2017

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments