Sir Jimmy Savile: Disc jockey, television presenter and tireless fundraiser for charity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

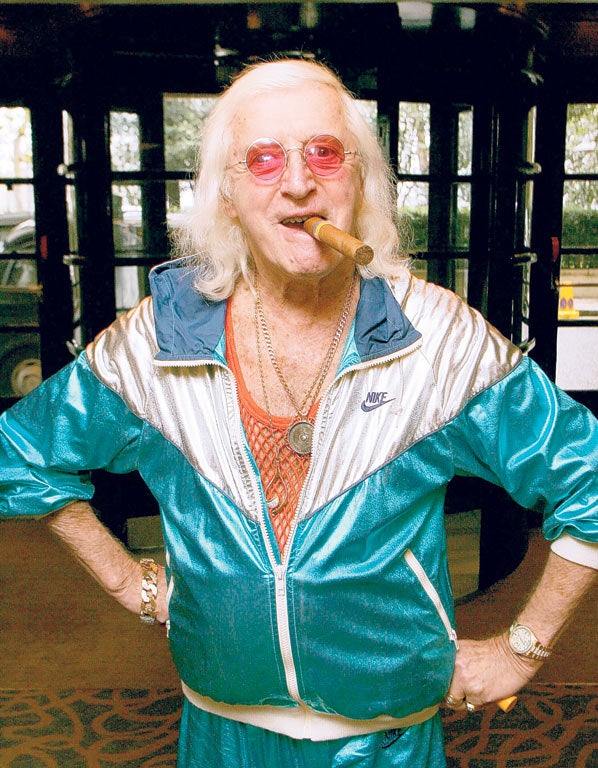

Your support makes all the difference.Jimmy Savile, the man who “fixed it” on television for countless children for almost 20 years, enjoyed a long career as a BBC radio disc jockey, raised more than £30m for charity and at the same time kept a six-inch Havana cigar almost permanently jammed between his teeth, dyed his hair platinum blond and always wore tracksuits, trainers and chunky jewellery. He was an enigma of the broadcasting era.

Although Savile started his showbusiness career as a disc jockey, he could never be pigeon-holed – he was simply a “personality”, some even said a saint (in fact, he received both a knighthood from the Queen and an honorary papal knighthood). Savile referred to everyone as “guys and gals” and had the knack of walking up to people in the street, talking to them, making them feel good and moving on. But behind the patter lay a hard-headed Yorkshire businessman who was devoted to helping others.

Raising money for those in need came after a childhood of poverty and a debilitating injury sustained while working as a miner. Born in Leeds in 1926, to a bookmaker’s clerk and his wife who lived in a three-storey terraced house, he was the youngest of seven children. “We always had a bed each, although there might be two or three of us in one room,” Savile later recalled.

At the age of two, he nearly died – the doctor signed a death certificate in expectation of the event. Savile could not remember what his illness was. “In those days,” he explained, “if you were poor you just died – it was no big deal.”

Poverty entitled him to a jar of free malt, from which he had a spoonful a day to combat rickets, free canvas and rubber-soled sandshoes, and free milk, as well as days out to Scarborough. Against this background, Savile had fund-raising ingrained into him as a child when his parents organised whist and beetle drives for charity.

At the outset of the Second World War, he earned five shillings a week as a pianist’s drummer, performing at the Leeds Mecca. He left St Anne’s Roman Catholic School, Leeds, at 14 and worked briefly in an office, before being called up as a Bevin Boy in 1942 to work down the mines, starting at South Kirkby Colliery, West Yorkshire.

But six years later, Savile’s days as a miner ended when he was blown up in a pit explosion at Waterloo Colliery, near Leeds, and left with a spinal injury that meant he could walk only with

the aid of two sticks and a steel spine jacket to make him stand up straight. With great determination, he combated his disability in just over three years.

By then, Savile had taken his first steps into the world of entertainment, albeit on a local level, when he started an early form of disco – “Grand Record Dances” – in a room owned by the Loyal Order of Ancient Shepherds above a café in Otley, where he wired a gramophone up to a radio, in the days before electric record players.

He subsequently travelled across Yorkshire with his records, claiming to have invented “disc-jockeying” and been the first to use two turntables, side by side. Then, he became a ballroom and dance-hall manager, at one stage responsible for 52 different Mecca venues across England. During this time, he dyed his natural light-brown hair blond and found it so popular that he kept it as a gimmick.

Savile came to the attention of Radio Luxembourg, which beamed to Britain the new pop music that youngsters wanted to hear rather than the bland diet broadcast by the BBC. He joined the station as a disc jockey in 1958 –

while still managing dance halls – and stayed for nine years, presenting shows such as Savile Club and Guys, Gals and Groups.

He joined Radio 1 in June 1968, a year after the BBC set it up as the first land-based pop station to combat the pirates who had broadcast from the sea and amassed a large following among Britain’s young. The first programme he conceived for Radio 1 was the Sunday-afternoon show Savile’s Travels, in which he went around with a tape recorder, meeting interesting and unusual people, and mixing the conversations with records.

In 1969, Savile dreamed up Speakeasy after the Rev Roy Trevivian, of the BBC’s religious department, told him that it had been allocated 45 minutes a week on Radio 1 and he wanted young |people to be able to talk about subjects that interested them. Savile continued on BBC radio until 1989, when he switched to commercial stations around the country.

By the time he joined Radio 1, he had already been seen on television as a regular presenter of Top of the Pops from its first episode, on New Year’s Day, 1964. The programme, which became Britain’s longest-running popular music show until it was axed in 2006, when he was brought back to co-host the final episode, was the first to feature hits from the singles chart every week, with acts miming their songs in the television studio, although there were live performances in later years.

That first week, Savile introduced acts such as Dusty Springfield, the Hollies, the Rolling Stones and the Dave

Clark Five. Top of the Pops, based on BBC radio’s Light Programme show Pick of the Pops, was first presented from a converted church in Manchester with a set resembling a coffee-bar disco and the disc jockeys sitting at turntables.

After doing a series of memorable “clunk, click, every trip” television commercials, beginning in 1971, to publicise the need to wear seat belts in cars, Savile found his greatest screen fame as host of Jim’ll Fix It (1975-94), giving viewers the chance to make their wildest dreams come true. It proved to be a hit family show, becoming a linchpin of BBC 1’s Saturday-evening schedule, and during its 19-year run received more than three million requests.

Among those for whom Jim fixed it were children who wanted to pilot Concorde and be a lion-tamer in a circus, as well as a 103-year-old man who achieved his lifetime’s ambition to drive a Formula One racing car. At its height in the late 1970s, Jim’ll Fix It attracted audiences of more than 15 million. In 1981, Savile also presented a 10-part series called Play It Safe, showing how tragic accidents involving children could be avoided.

Despite this, and the popularity of Jim’ll Fix It with children, Savile had no paternal instincts. “I actually don’t care for children,” he said. “Children’s instincts are enormous and, when they come to me on Jim’ll Fix It, they sense I’m not parental or yukky-yukky about kids. They madly want to be on the show with me and they know they have to work to get my approval.”

Fame brought Savile invitations to Chequers on Boxing Day during Margaret Thatcher’s days as Prime Minister. He was said to be the only showbusiness star who could get away with teasing the Iron Lady, turning up

one year in a T-shirt with baubles and a large bell sewn on it, and inviting her to “ring my bell”.

Celebrity status also enabled him to raise millions for charitable causes. In 1968, he went to Stoke Mandeville Hospital in Buckinghamshire to give out prizes and ended up staying as a voluntary helper, working there as a porter, as he did at Leeds Infirmary – where he was treated after his mining accident – and Broadmoor Hospital. His endeavours helped to raise £12m to build the National Spinal Injuries Centre at Stoke Mandeville.

A keep-fit fanatic, he also ran more than 200 marathons in aid of charity – last completing the London Marathon in 2005, at the age of 78. In 1989, a Savile’s Time Travels compilation album titled 20 Golden Hits of 1969 sold more than 250,000 copies and earned the star a platinum disc. His £140,000 royalties were donated to Stoke Mandeville Hospital.

At the same time, he amassed considerable wealth himself, enabling him to buy Rolls-Royces, enjoy regular cruises and treat his mother, Agnes, whom he called “The Duchess”. Savile adored his mother and lived with her on and off until she died in 1973, although he admitted that their love was not demonstrative. “There were no kisses, no hugs, nothing,” he said. “But what we had was rapport. I didn’t need to say things to her and she didn’t need to say things to me. I had an enormous affection for her, but not an emotional one.”

In his later years, Savile moved between five spartanly furnished flats dotted around the country while constantly travelling to do charity work. He also had rooms at Broadmoor Hospital and Stoke Mandeville, but he never married. “I quite envy people who have been in love,” he once said, “but how could I with my lifestyle?” He had no close friends, either, but he objected to Professor Anthony Clare’s diagnosis, on the BBC Radio 4 programme In the Psychiatrist’s Chair, that he was suffering from “a profound psychological malaise with its roots in [his] materially deprived, emotionally somewhat indifferent childhood”.

However, Savile did admit an attempt to make up for his younger days when he explained his reason for smoking Havana cigars. “The cigars are symbolic more than anything else,” he said. “They epitomise the opposite of my first job down the pit.”

Savile’s autobiography, As It Happens, was published in 1974 (and in paperback two years later as Love is an Uphill Thing).

James Wilson Vincent Savile, broadcaster and charity worker: born Leeds 31 October 1926; OBE 1971, Hon KCSG (Holy See) 1982, Kt 1990; died Leeds 29 October 2011.

31.10.1926

On the day he was born...

The escapologist Harry Houdini died at the age of 52. A student, Gordon Whitehead, tested his claim that he could withstand heavy blows to the abdomen, but before he had had chance to tense his muscles. He died of peritonitis.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments