Sir Howard Hodgkin obituary: One of Britain's greatest abstract painters of the post-war period

Turner Prize winner Sir Howard Hodgkin, considered among Britain’s finest contemporary artists, saw his paintings as distilled memories and created abstract evocations of emotion with potent, compelling use of colour

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sir Howard Hodgkin, who has died aged 84, was something of a rebel, though anyone meeting him for the first time would not readily have guessed so. His voice, always fairly plummy, made him sound the very epitome of respectability, though he was by no means a ready talker on the subject that concerned him most: painting. Painting was his life-long passion, of course – he knew that he wanted to be a painter and nothing but a painter from the age of five, immediately after he had drawn a picture of a woman with a red face and bushy hair – but he always found it difficult to talk about that which consumed him until his dying day. In fact, he could be maddeningly obtuse, high-handed, and even downright patronising when questioned about his own work. Or just puzzlingly, vexingly silent, looking down.

Or, after a long pause, he might say something to you such as the following: "I think you will find that I have already answered that question in a statement I made in the autumn issue of Art for Art’s Sake." Or some such. This was maddening in the extreme. There was a reason for it though. According to Howard, paintings existed to be looked at, absorbed, slowly and painstakingly, by the eye. He thought that nothing should come between the painting and the scrutinising eye, and certainly nothing as vulgar as mere words, which he once described as the Englishman’s disease. When in the presence of the great ones – his two favourites were Poussin and Seurat – the better part was an awestruck, reverential silence. Why sully the air with useless and inadequate words?

I first met him in the year 2000 at his studio less than 50 yards from the British Museum. The visit proved to be something of an unfolding surprise. You entered by what for all intents and purposes seemed like the front door of a substantial Georgian house, and then you were quickly shuffled though and into a vast space of a much more utilitarian character altogether, with brick walls painted a stark white, which looked as if it had been built for a purpose other than comfortable human accommodation. That was true. The space itself had once been a dairy, though not since the Second World War. Now it was Howard’s painting studio, though you would not easily have known that fact either because there were no paintings to be seen, not when I first casually glanced around. In fact, I later discovered that there were indeed paintings in that room, several of them, but they were turned to face the wall – like prisoners due to suffer some terrible fate – and covered with white sheets. Howard would turn one round to face you if you really insisted, but they were never on open public display. Howard was cagey about showing new work. To anyone. Paintings often took him years to make, sometimes more than a decade – you can find evidence of his tortoise-slow making process if you read his exhibition captions – and it would not have been quite right, you guessed, to happen upon something in the making. It would have been a bit of a violation, and even perhaps an act of impertinence. It is also true to say that he was cagey about having paintings on display at all, his own or other people’s, in the studio or elsewhere. Perhaps they were safer, less threatening of the possibility of violent confrontation, when kept under wraps.

I call him a rebel, but he was also quite a well-connected rebel. It was entirely appropriate that he should have made Bloomsbury his home and place of work because he was one of the riper Bloomsberries himself. In fact, he was a cousin of the painter and critic Roger Fry. Howard himself was born in Hammersmith, west London in 1932, and his father worked as a manager for Imperial Chemical Industries. In fact, quite a few of his forebears had been fairly illustrious, from the distantly related Luke Howard (1772-1864), the so called "father of meteorology", who first identified cloud formations, to the physician after whom Hodgkin’s disease was named, and the poet Robert Bridges.

The rebellious side to Gordon Howard Eliot Hodgkin’s – to give him his full name – nature was put on full display during his school days. He got into the habit of running away from the various boarding schools to which he was sent. He was then dispatched to Eton, where he stayed put for just 18 months before running away from that establishment too. Eton, he told me once, had been horrible. Well, almost horrible. What exactly did he do there? "Messed about". In fact, there was a little more to it than that. His art teacher during his brief sojourn at Eton, a man called Wilfred Blunt (brother to the treacherous art historian Anthony), introduced him to Indian miniature painting, and that passion for Indian miniatures – Howard owned a considerable collection – stayed with him life-long. One of the things he loved so much about Indian miniatures were the elephants. That always struck me as odd because as a painter Howard had little to do with nature. In fact, he had almost nothing to do with the mimetic representation of people or animals or objects at all, and less and less so as he grew into his maturity as an artist. Unsurprising, you might say. After all, wasn’t Howard Hodgkin fundamentally an abstract painter? In fact, was he not one of our greatest abstract painters of the post-war period?

The answers to two those two questions are both puzzling and complicated – rather like Howard’s own character. When asked about the question of abstraction versus representation, and where exactly he himself stood, he would repeat what was to become his mantra (you find this artfully crafted statement of his popping up everywhere, cut-and-pasted by one idle journalist after another): "I am a representational painter, but not a painter of appearances. I paint representational pictures of emotional situations." So there you have it, clear as mud. He is. And yet he most certainly isn’t, perish the thought.

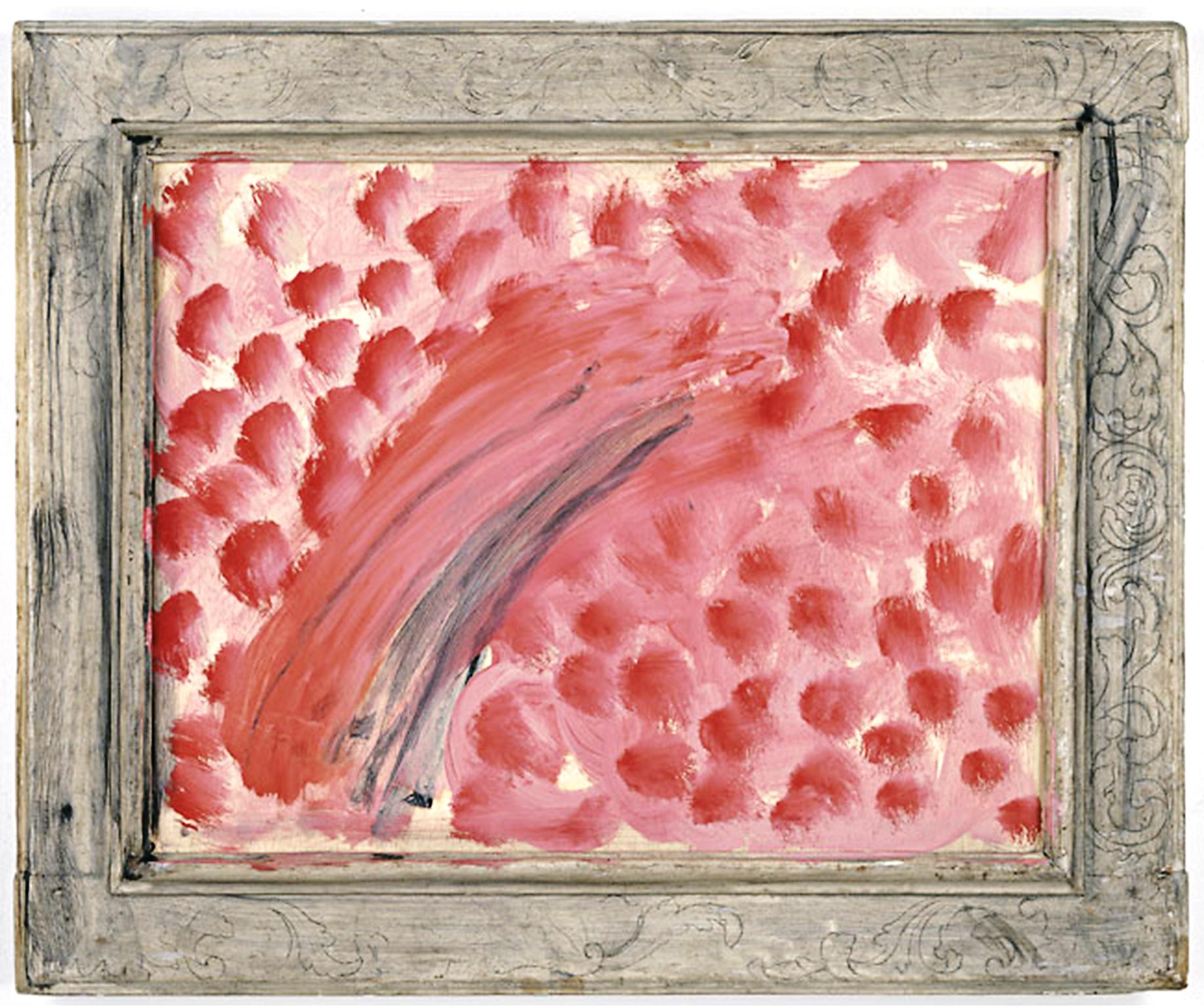

He regarded his paintings as distilled memories, evocations of remembered places and people. They always looked and felt warm, emotionally. There was nothing severe or angular or geometric or austere or dry or even pessimistic about Howard’s work, never any suggestion that what he was up to might be distantly related to the poker-faced disciplines of science or arithmetic. It was all about the upwelling – and perhaps even the overwelling – of human feeling. It was the kind of painting which always kept some idea of its subject in mind. Although he never painted animals, he was happy to remember the human animal in its various social situations.

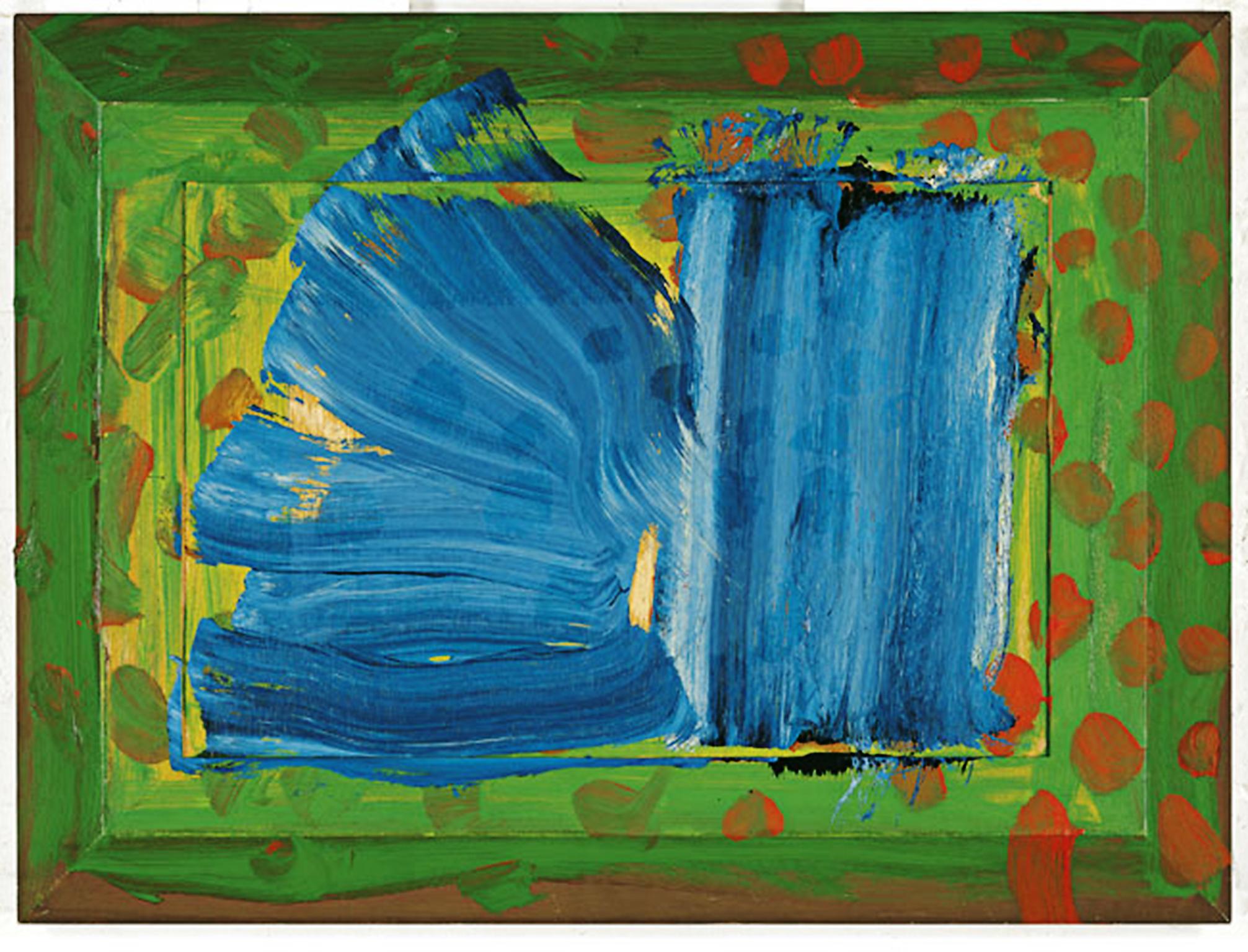

What is clear about his paintings is that they are loaded – often almost overloaded – with emotion and mood. His brush strokes, often quite as gorgeous as an excellent bit of hair styling, make that evident: the great, sweeping symphonic curves; the luscious tampings; those rainbow-like arcs; that habit he had of letting the paint bleed over onto the frame (which would often be shriekingly kitschy), as if everything was far too uncontainable. The shapes could be unusual – he was even known to paint on a circular breadboard. He preferred board to canvas because board could be attacked; board could resist the painter’s punishingly relentless daily assault; a painting on board could be reworked for just as long as was necessary. In fact, for quite as long as it would take to unlock the image.

His paintings often feel luscious, loaded with sensuality. The titles of the individual works also feel like a bit of a tease, perhaps even a private joke. Here are a few of them, plucked forth at random: Close Up, Strictly Personal, Blushy, Hello. Those titles are entirely characteristic. They sound casually anecdotal. They edge, though somewhat coyly, in the direction of storytelling. You could call them low-brow entry points to high art. They might even be happy, you sometimes felt, to enjoy a second life as captions in Hello! magazine.

That first conversation with him in 2000 went very badly indeed. He barely told me anything that I wanted to know. He scolded me or went silent on me for most of our so-called conversation. Things were a little easier the second time around. By then, he recognised me, of course. A little more of himself seemed to emerge from the shadows. I recognised that he himself was nervous. Don’t expect many quotes he warned me beforehand on the phone. Don’t expect me to say very much. You can make it all up if you like. Was that last a joke? A joke. Which meant that we were likely to be better company for each other.

Once unbuttoned, I discovered, Howard could be a very emotional man. We began to talk about the role of the artist in society. This time we were sitting in the basement of his studio, where he kept a library of several thousand books. It was a fairly dark environment for a conversation, illuminated only by desk lamps. Perhaps that also made things a little easier, the slight whiff of secretiveness. He wanted to read something to me, he told me, an extract from a novel by Somerset Maugham, which would illustrate perfectly the idea of the nobility of the artist’s calling. He scurried away to find it with great eagerness – I remember thinking that he looked a little like Alice’s white rabbit as he hurried away from me into the penumbra – and then, having returned with a book of some age, he read it to me, the chosen extract, at some considerable length, and as he did so, his eyes brimmed with tears. It was maudlin stuff, in the extreme, but it had moved him deeply.

It took some time for Howard to be singled out as a painter of some promise. His first solo exhibition was at Arthur Tooth & Sons in 1962, when he was 30 years old. Tooth was more than happy to show him. In fact, the gallery wanted to show him more frequently than Howard wanted to be shown, and he baulked at the alarming generosity of the offer. He knew how difficult it would always be to squeeze a painting out of himself. He did not want to turn himself into a production line. And then the exhibitions followed steadily, culminating in a retrospective at Tate Britain in 2006, which then travelled on to the Reina Sofia in Madrid. It encompassed 50 years of work. Nicholas Serota, in his catalogue introduction, praised the subtlety and the energy of the work, its vitality and its versatility.

I feel that Howard did quite not become the kind of painter that the more cerebral part of his nature rather wanted to be. He loved the idea of of being a classical artist whose work respected the unities and – like Poussin – had a strong sense of composition, but his actual nature, his instincts, seemed to be fighting a rearguard action against what his brain desired. He was, in short, a Romantic at heart, though one who played his cards close to his chest. Even his professed love of classicism seemed slightly suspect. He would talk a great deal about the classicism of Poussin and his compositional rigour, but what he loved about one particular Poussin which he once described to me so lovingly – it is in the Dulwich Picture Gallery, and it is called Rinaldo and Armida - was its brilliant use of colour, and, more specifically, the ravishing orange of Rinaldo’s shorts. (Howard himself was a brilliant colourist and one of his great early passions was Matisse, one of the greatest colourists of them all.) So when he once stated that he longed to make pictures that would speak for themselves and have the finality of something that observed the classical unities, he failed to mention that it was equally important for him to share his feelings – and he did that, supremely well, life-long, this tongue-tied man.

Gordon Howard Eliot Hodgkin (Sir Howard Hodgkin), artist: born Hammersmith 6 August 1932; died 9 March 2017

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments