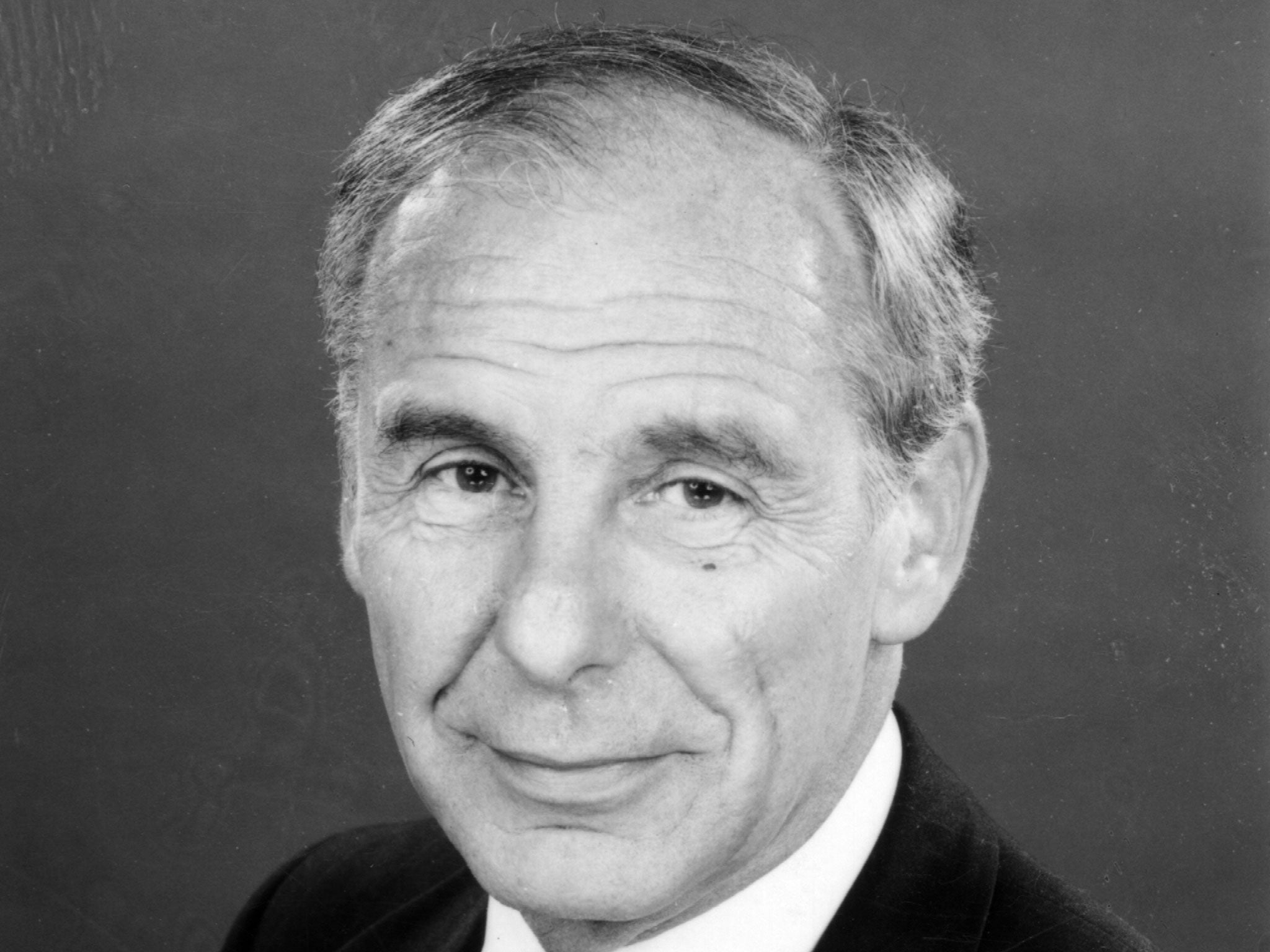

Sir Christopher Curwen: Security services officer

Head of MI6 whose achievements included bringing the double agent Oleg Gordievsky out of the Soviet Union

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A signal with a Harrods shopping bag by a lamp-post on a Moscow street corner in July 1985 was the cue for Christopher Curwen, MI6’s last Cold War “C”, to set in motion a long-prepared plan to spirit to the West and safety a valued spy. The man whom the newly appointed head of the British Secret Intelligence Service helped to escape from almost certain assassination was Oleg Gordievsky, a KGB officer who for a decade had served British interests.

Gordievsky, who accorded Curwen and his colleagues the accolade of being “the real defenders of democracy”, had suddenly been recalled to Moscow and interrogated that summer after a long posting in London. Curwen was one of the few who knew every detail of the intelligence with which the KGB officer had kept Britain posted of what would turn out to be the death-throes of the Soviet Union. So useful were Gordievsky’s contributions that even before the threat to his life in 1985, the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, expressed concern that he and his family should be protected.

The way that challenge was successfully met – and a Foreign Office career played out around the world – was one of the factors that took Curwen on from being “C” and into the heart of British security policy-making as Cabinet Office Deputy Secretary, and later, in retirement, as a member of the Security Commission, a body of trusted figures charged with investigating security breaches in the public services.

While Gordievsky, in fear for his life, and carrying, one account says, a British Safeway supermarket bag, stood at the assigned street corner and stared at a British contact approaching with a Harrods bag, back in Britain Curwen was alerted to seek permission from the Prime Minister to have the Russian driven across the Soviet border to Finland in an SIS car and on via Norway to be flown to London. Curwen visited Gordievsky at a safe house in the Midlands, and having interviewed him was able to reassure sceptics who feared he might have been compromised during his stay in Moscow and might have returned as a double agent.

Curwen’s familiarity with Gordievsky’s intelligence material went back to the bluff and double-bluff of the previous few years when Gordievsky had warned of the efforts of an MI5 member, Michael Bettaney, to pass information to the then KGB residence chief, Arkady Guk, who had failed to take up Bettaney’s first anonymous offer, a package pushed through a letter-box, fearing it to be a trap.

Bettaney was unmasked and sentenced to 23 years’ imprisonment in April 1984. Apart from Curwen and his colleagues only Thatcher, and her then Foreign and Home Secretaries, respectively Sir Geoffrey Howe and Leon Brittan, knew he had been convicted thanks to intelligence from Gordievsky (so sensitive was the evidence that press and public had been excluded from his trial). The story is told by Christopher Andrew in The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009).

To help Gordievsky, Curwen had called on the assistance of Sir Robert Armstrong, the Cabinet Secretary, to persuade Thatcher to let the services use publicity given to Guk as a reason to expel him, “since”, in Curwen’s words, “Guk has always been most careful not to become directly involved in KGB agent-running operations and is likely to be even more careful in the future”.

Guk was expelled on 14 May 1984, and Moscow expelled a British diplomat in return. But by the end of 1984 light was appearing in British-Soviet relations with the advent at the head of a delegation to London of Mikhail Gorbachev, the future leader who by 1991 would have dismantled the USSR. Curwen was among those who had done the groundwork of keeping the British government well-informed of thinking in Moscow, where Party leaders had been veering from paranoia that the West was preparing a nuclear first strike to noticeable thaw. Cold War practice nevertheless endured into Curwen’s time as “C”, with large mutual tit-for-tat expulsions in September 1985.

Christopher Keith Curwen was the son of an Anglican clergyman, the Rev RM Curwen, rector of parishes on the Isle of Wight and in Surrey. He attended Sherborne School, and read history at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge. His National Service at the age of 20 as a 2nd lieutenant in the 4th Queen’s Own Hussars, part of the Royal Armoured Corps, gained him a mention in despatches, recorded in the London Gazette of 19 May 1950, “in recognition of gallant and distinguished services in Malaya during the period 1st July 1949 to 31st December 1949”, on an operation under Captain, later Major, Hugh Marrack.

At this time Communist insurgents in Malaya were targeting the inexperienced young soldiers arriving from Britain, and Curwen faced hazards including jungle traps of concealed pits studded with sharpened bamboo stakes and an iron blade that would decapitate the man following any soldier who stepped on a hidden trip-wire. By 1952 he had joined the Foreign Office, and was posted to Bangkok in 1954 then Vientiane, Laos, in 1956. His observations on Thai and Malay politics in the 1950s are cited in a number of books by South-East Asia scholars including the Cambridge historian Nicholas Tarling. Curwen then spent periods in London alternating with postings to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, in 1963, Washington in 1968, and Geneva in 1977.

Christopher Keith Curwen, spymaster: born Surrey 9 April 1929; CMG 1982, KCMG 1986; married 1956 Noom Tai (divorced 1977; one son, two daughters), 1977 Helen Anne Stirling (one son, one daughter); died Bath 18 December 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments