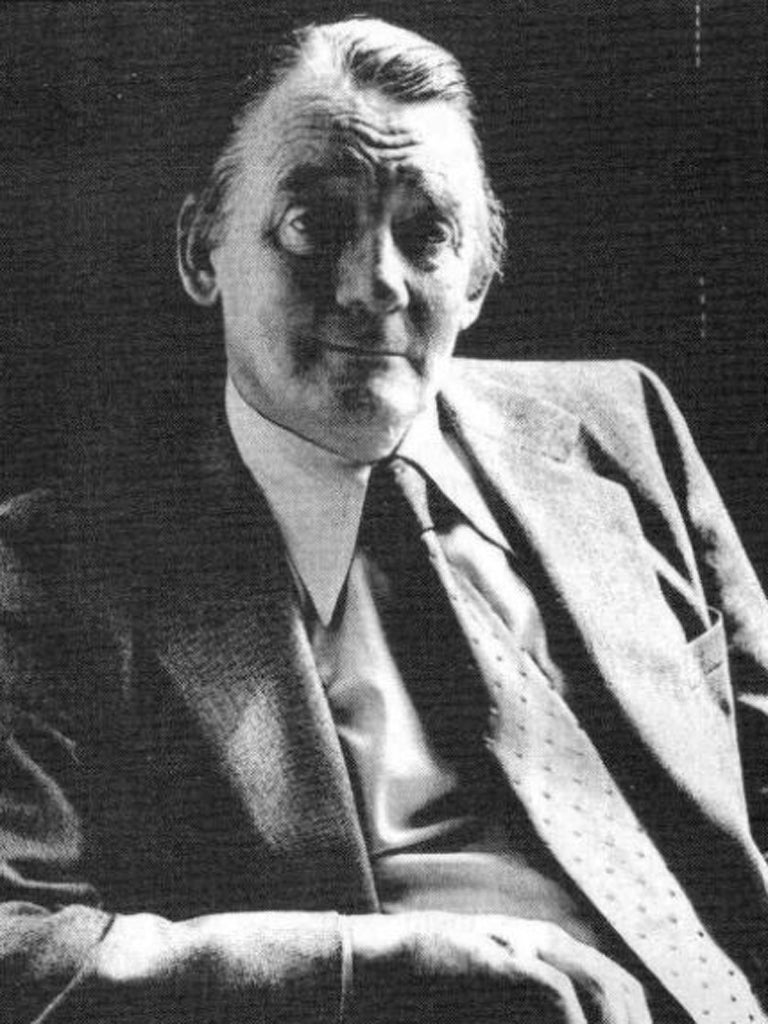

Sir Christopher Booth: Clinical scientist and medical historian

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Christopher Booth was a major figure in academic medicine and a passionate advocate for clinical research during the latter half of the last century. His career reflects the successes and travails of clinical academic medicine at a time of unparallelled advances in basic biomedical science. As an historian he saw issues with a clarity and long-term perspective often lacking in many of his contemporaries.

His own distinction as a physician scientist arose from pioneering research in diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, most notably conducted on patients who had undergone intestinal resection; he and David Mollin were the first to show that vitamin B12 was absorbed in the distal part of the small intestine. This exemplified his approach: the elucidation of biological and pathological mechanisms through clinical research, for which his favourite term was "clinical science", coined by Thomas Lewis.

This work was conducted at the Postgraduate Medical School at Hammersmith Hospital, where he had initially gone in 1952 as a junior doctor working with John McMichael, Professor and Director of the Department of Medicine. Booth subsequently succeeded Sheila Sherlock as head of the gastroenterology unit.

His appointment as successor to McMichael in 1966 was greeted with surprise by some, but he changed the department's orientation from applied physiology to research on mechanisms of disease, emphasising immunology and cell biology. His influence is felt today with a cadre of clinician scientists who hold key senior academic appointments. He was especially pleased when three of his Hammersmith protégés received knighthoods in the last New Year's honours.

Booth loved the Hammersmith, describing his post there as the best job in British medicine, and in a lecture celebrating the first 50 years of the RPMS he said, "it is a place where there is always a fizz of excitement that gives a champagne quality to every day". But in 1977, Booth became Director of the Medical Research Council's Clinical Research Centre (CRC) at Northwick Park, a newly built district general hospital in North-west London. This was to be a major challenge.

The MRC's vision was for the CRC to undertake research on common diseases largely neglected by the increasingly specialised academic units of the traditional teaching hospitals. Booth wholeheartedly embraced this philosophy and promoted research programmes in areas such as psychiatry, sexually transmitted diseases and other infectious diseases and the genetics of skin and cardiovascular disease. However, by the early 1980s the MRC was under pressure to demonstrate value for money, the NHS, was under financial pressure and it became increasingly clear at Northwick Park that the two cultures – of the NHS medical staff whose priority was to deliver a district service, and the MRC-funded clinician scientists – made uneasy bedfellows. In response to these pressures the MRC set up reviews of the work of the CRC, culminating in its eventual closure.

Booth was a notable medical historian, inspired by his love of the Dales (his mother had restored a cottage in Wensleydale). He brought the lives and influence of Dales doctors to worldwide attention; this was the basis of his election to the American Philosophical Society. He published four books and more than 50 papers on historical topics, became Harveian Librarian of the Royal College of Physicians and helped establish the History of 20th Century Medicine group supported by the Wellcome Trust, which survives today at Queen Mary University of London.

Booth was born in Farnham, and on leaving Sedbergh School in 1942 was conscripted as an Ordinary Seaman, becoming one of the "Frogmen of Burma" of the Sea Reconnaissance Unit. As well as his knighthood he received many honours, and was President of the BMA (1986-87) and the Royal Society of Medicine (1988-89). In retirement he married Joyce Singleton, with whom he found domestic contentment. He was at his happiest relaxing with her in the garden of their cottage in Wensleydale.

Christopher Charles Booth, physician, academic and medical historian: born Farnham, Surrey 22 June 1924; Kt 1983; married 1959 Lavinia Loughridge (one son, one daughter), 1970 Soad Tabaqchali (one daughter), 2001 Joyce Singleton; died 13 July 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments