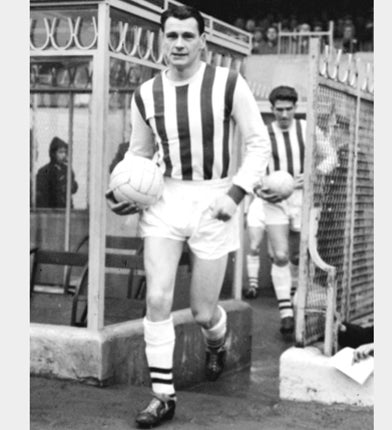

Sir Bobby Robson: Esteemed football player and manager who led England to the World Cup semi-finals

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With his rumpled features and crooked smile, he could look crushed and weary, but when Bobby Robson began holding forth on his beloved game, those rheumy eyes would sparkle and his overwhelming enthusiasm would captivate all but the most cynical of listeners.

Almost always, despite the endearing malapropisms with which his conversation was scattered, his homespun philosophy would offer an oasis of wholesome sanity in the self-obsessed world of modern top-flight football.

Robson was the doyen of the British game, a national institution whose public image had been comprehensively rehabilitated since the days of his unfair and frequently hysterical media maulings during his reign as England boss in the 1980s. In fact, he was an immensely able, honourable manager who never deserved the tabloid-fed calumny which descended on his head. His international record bears favourable comparison with all but one of his predecessors – Sir Alf Ramsey, whose side lifted the World Cup in 1966.

Eventually, when his career could be placed in perspective, and particularly following his emotional stint in charge of his childhood favourites, Newcastle United (1999-2004), his public stock rose tremendously.

Their approbation, and the chance to guide his country's fortunes, sprang from his achievements at club level with unfashionable Ipswich Town, for whom Robson had operated on a comparative shoestring to create delightful sides which could hold their own, and sometimes more, against the finest in the land. Once ensconced on the international front, he never brought home a trophy, but Robson's England endured horribly unlucky elimination from successive World Cup tournaments and had their moments of triumph along the way.

In addition, it should not be forgotten that the north-easterner had been a good wing-half-cum-inside-forward who won a score of caps at a time when there was no shortage of high-quality performers in both positions.

Robson hailed from the mining community of Sacriston in Co Durham, the fourth of five sons of a father who missed only one shift at the coalface in 51 years. Having noted the bleakness of that life, young Bobby was determined to avoid the pit and did so at first by becoming an apprentice electrician at his neighbourhood colliery.

Of course, Robson's ultimate salvation was football. It was both his obsession – later he would describe it as his drug – and what he did best. After starring at schoolboy level, he was given trials by Middlesbrough and Southampton, both of whom rejected him. Nothing daunted, the 15-year-old inside-forward continued to impress and two years later a posse of clubs was hunting his signature.

Robson chose Fulham, enlisting with the Londoners in May 1950 and making his First Division début within a year. He revelled in the friendly atmosphere fostered by the chairman Tommy Trinder and shone in an enterprising line-up which also included Johnny Haynes. Despite relegation in 1952, Robson made steady personal progress, a confident but level-headed young fellow who brought both skill and industry to his twin roles of creating and scoring goals. Inevitably he attracted attention from the top grade and in March 1956 he joined West Bromwich Albion, a successful club at the time, for a then-hefty £25,000.

When England recognition arrived in November 1957, Robson responded with two début goals in a 4-0 rout of France, suggesting that a lengthy international stint was in prospect. But selection policy was markedly inconsistent in those days, the team being picked by committee, and soon he was discarded. It was to be two years before he regained his place.

During 1960/61, Walter Winterbottom's England team enjoyed a glorious undefeated sequence, winning seven games and drawing one, scoring 44 goals in the process. Sadly, they peaked too soon for the 1962 World Cup, just before which the 29-year-old Albion skipper was dropped, never to play for his country again. However, international football had not seen the last of Bobby Robson.

West Bromwich, though, had. During his Midlands sojourn he had supplemented what was then a paltry income for a married man with two (later three) sons by coaching schoolboys. But with the lifting of football's maximum wage restrictions in 1961, the way was clear for clubs to reward their players more handsomely. Some did, Albion didn't and Robson demanded a transfer, returning to Fulham for £20,000 in August 1962.

Back at Craven Cottage, he flourished in a mainly defensive role, bringing class to an indifferent side's annual struggle to avoid demotion from the First Division. Meanwhile, having been encouraged by Winterbottom to develop his coaching, Robson assisted Oxford University, and when he retired as a player in 1967 he set his sights on management.

After rejecting offers to coach Arsenal and to become player-boss of Southend United, he took charge of Vancouver Royals with the great Hungarian hero Ferenc Puskás before returning to Fulham in January 1968 to take over an ailing club.

Robson was unable to prevent relegation and, despite major reorganisation of his staff, the Cottagers performed poorly in Division Two and the rookie manager strove, at times, to exercise authority over former colleagues. Following a row with a director, Robson was sacked in November and found himself on the dole.

However, his luck was about to turn. After scouting briefly for Chelsea, he became boss of Ipswich Town in January 1969, thus beginning one of the most fruitful periods of his life. Not that it was all plain sailing at Portman Road. Despite establishing a rapport with the generous-spirited Cobbold family, who owned the club, Robson began by presiding over several disappointing seasons at the wrong end of the First Division. He had inherited a weak side and there were confrontations with players, including one bout of fisticuffs, as he settled in.

When a vocal minority of Ipswich fans demanded his sacking, Robson feared the worst. Instead, the board persevered with their man, and, gradually, the tide turned. Despite not having the cash to compete on equal terms with rich clubs, he assembled a first-rate team, built around the likes of Mick Mills, Kevin Beattie and Allan Hunter. In 1973 they finished fourth in the table, equalling the feat in 1974, then improving to third in 1975. Thereafter they finished out of the top six only once in a decade, missing the title only narrowly on several occasions.

They did have their moments, however, winning the Uefa Cup in 1981, though for the sheer joy it brought, even that could not equal their heady and massively popular victory over Arsenal in the 1978 FA Cup final.

An operator of Robson's calibre was bound to receive periodic offers. But as the chances to leave Portman Road came in, so he spurned them. He could have gone to Leeds, Newcastle, Barcelona and Manchester United among others; but instead he remained loyal to Ipswich and the Cobbolds, treating them as they had treated him. It did him huge credit.

However, there was one temptation from which Robson could not walk away. He had been interviewed for the England post when Don Revie upped sticks in 1977 and had run the international "B" team between 1978 and 1982. When the opportunity of the top job came his way in 1982, he accepted.

He got off to a solid start, despite early vilification for the axing of Kevin Keegan. But, predictably in view of England's failure to reach the 1984 European Championship finals, his "honeymoon" was woefully short. After one Wembley defeat by Russia he was spat on and showered with beer, but that was nothing compared to what certain newspapers had in store. Chief persecutors were The Sun, which produced badges proclaiming "Robson Out, Clough In", though that, in its turn, was mild compared with what would follow later letdowns.

Around this time Robson was head-hunted once more by Barcelona, but he demonstrated his strength of character by refusing the Spaniards for a second time. In the short term he was rewarded by one of the finest results England have ever managed, victory in Brazil, but by now all attention was centred on the 1986 World Cup. England duly qualified, then stuttered in their early matches in Mexico before recovering, thanks largely to Gary Lineker's hat-trick against Poland, to reach a quarter-final against the eventual champions, Argentina. That day Robson's men were undone by Diego Maradona, who scored twice in his side's 2-1 win. The first was the infamous "Hand of God" goal, and the second was a work of pure genius. England threatened a draw, but couldn't quite achieve it; they had been unlucky, but Robson deserved praise for orchestrating a noble effort.

It wasn't quite like that in 1988 when England lost all their games in the European Championship finals and returned home from Germany in disgrace. Now Bobby Robson's relations with the press hit a new low. He was castigated mercilessly, being told to "Go in the Name of God". Then, after a drab showing against Saudi Arabia, this was amended to "Go in the Name of Allah". Very droll.

Clearly there was a limit to what one man could take and, after England scraped into the 1990 World Cup finals in Italy, Robson announced that he would quit after the tournament. The build-up games inspired little faith but the team progressed, with a measure of good fortune, to a semi-final confrontation with West Germany. Here, for the first time, they played like potential champions, with the maverick Paul Gascoigne showing signs of realising his phenomenal potential. But just as Robson was poised on the threshold of emulating Sir Alf Ramsey by reaching a World Cup final, luck deserted him. The Germans having taken a fortunate lead, England equalised through Lineker and proved the stronger side, only to die the most dreaded of soccer deaths, by penalty shoot-out.

At least, however, an emotional Robson could bow out on a decent note. It was the least he merited after eight years in which he had presided over 47 victories, 30 draws and only 18 defeats, as well as carrying out vast amounts of unsung youth coaching work.

If there were ever any doubt about his ability, it was laid to rest emphatically in his subsequent career. He led PSV Eindhoven to two Dutch titles, thus laying to rest the championship bogey that had haunted him at Ipswich. Then came a move to Sporting Lisbon, which ended surprisingly in the sack, and a more successful spell with Porto, whom he guided to a European Cup semi-final in 1994 before winning two more titles.

After undergoing a second cancer operation in 1995 (the first had been in 1992), Robson recovered rapidly and turned down the chance of managing Arsenal. Still, though, his drive remained strong and a year later, aged 63, at last he accepted an invitation from Barcelona. In his first term, despite the recruitment of the star Brazilian striker Ronaldo, the side made an uncertain start and as the pressure of colossal expectation mounted, Robson ran into political problems with the autocratic club president Josep Nuñez. By New Year 1997, the Ajax coach Louis van Gaal had been lined up to replace Robson at season's end, but the Englishman embarrassed his employers by inspiring his men to double glory, Barcelona beating Paris St-Germain to lift the European Cup-Winners' Cup and Real Betis to take the Spanish Cup.

Now he was impossible to sack, so when van Gaal arrived for 1997/98, Robson was shunted "upstairs" to become director of recruitment, a glorified chief scout, a post he held for a year before taking over again at PSV.

In 1999 he returned to England and accepted a Football Association offer to become mentor to the next generation of England coaches, but in September he got the call from the club he had loved as long as he could remember, Newcastle United.

At St James' Park, where he replaced Ruud Gullit, he found a strife-torn club at the foot of the Premiership; morale was low, indiscipline was rife and there were wounds to heal. He began by restoring Alan Shearer (who had been dropped by the Dutchman) to the side and the England centre-forward responded by scoring five goals in Robson's first home match, an 8-0 annihilation of Sheffield Wednesday.

The new boss immediately infused the place with his infectious enthusiasm. He overhauled the coaching regime and began team-building, at first without much money, but eventually with a substantial budget. He transformed United's fortunes. In that first campaign they reached the semi-finals of the FA Cup and enjoyed an enlivening Uefa Cup run. Then, after another season of consolidation, they topped the table in December before finishing fourth in 2001/02. The following summer Robson, who had been appointed CBE in 1991, was knighted.

Newcastle rose to third in 2002/03 and attained the second group phase of the Champions League. In 2003/04 they made an appearance in the Uefa Cup semi-finals, where they lost to Marseille, offering compensation for dipping to fifth place in the League. All the while Robson represented traditional and sensible sporting values while continuing to radiate his passion for the game, and at times he was understandably perplexed by the boorish or careless attitudes of some of the young millionaires in his charge.

Some observers doubted whether a septuagenarian was capable of controlling the volatile likes of Craig Bellamy and Lee Bowyer, and on the eve of the 2004/05 season, Robson's position was undermined by the chairman, Freddy Shepherd – one of the directors caught mocking the fans so disgracefully – who announced that Robson's contract would not be renewed in the spring. At the end of August Robson was summarily sacked by Shepherd, but on the day of his departure it was his and not the chairman's dignity which shone through the storm clouds gathering over St James' Park.

Even after that, after everything, Robson remained eager to be involved in football, and in January 2006, now aged 73, he was named as consultant to the new Republic of Ireland boss Steve Staunton. Soon, there followed a third successful cancer operation, though his vulnerability was underlined that August when, after being appointed honorary president of Ipswich Town, he fell ill 10 minutes into their game against Crystal Palace.

Robson stepped down from his Irish role in November 2007, and in March 2008, as he launched a foundation at Newcastle's Freeman Hospital to help in the fight against cancer, he spoke of battling the disease for the fifth time. Already the new charity has raised more than £1.3m and he was still campaigning for it indomitably on Sunday, when he attended a fundraising game, a re-run of the 1990 England-Germany semi-final, at St. James' Park.

Bobby Robson was a sensitive and decent man, a truly accomplished manager who rose courageously above an army of petty tormentors. Though he never achieved his ambitions of lifting the World Cup or the English League crown, he came close enough to earn real and lasting honour in the game to which he devoted his life.

Robert William Robson, footballer and football manager: born Sacriston, Co Durham 18 February 1933; played for Fulham 1950-56, 1962-67, West Bromwich Albion 1956-62; capped 20 times for England 1957-62; manager, Vancouver Royals 1967-68, Fulham 1968, Ipswich Town 1969-82, England 1982-90, PSV Eindhoven 1990-92, 1998-99, Sporting Lisbon 1992-93, Porto 1993-96, Barcelona 1996-97, Newcastle United 1999-2004; CBE 1991; Head Coach, PSV Eindhoven 1998-99; Kt 2002; International Football Consultant, Republic of Ireland Football Team 2006-2007; married 1955 Elsie Gray (three sons); died Co Durham 31 July 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments