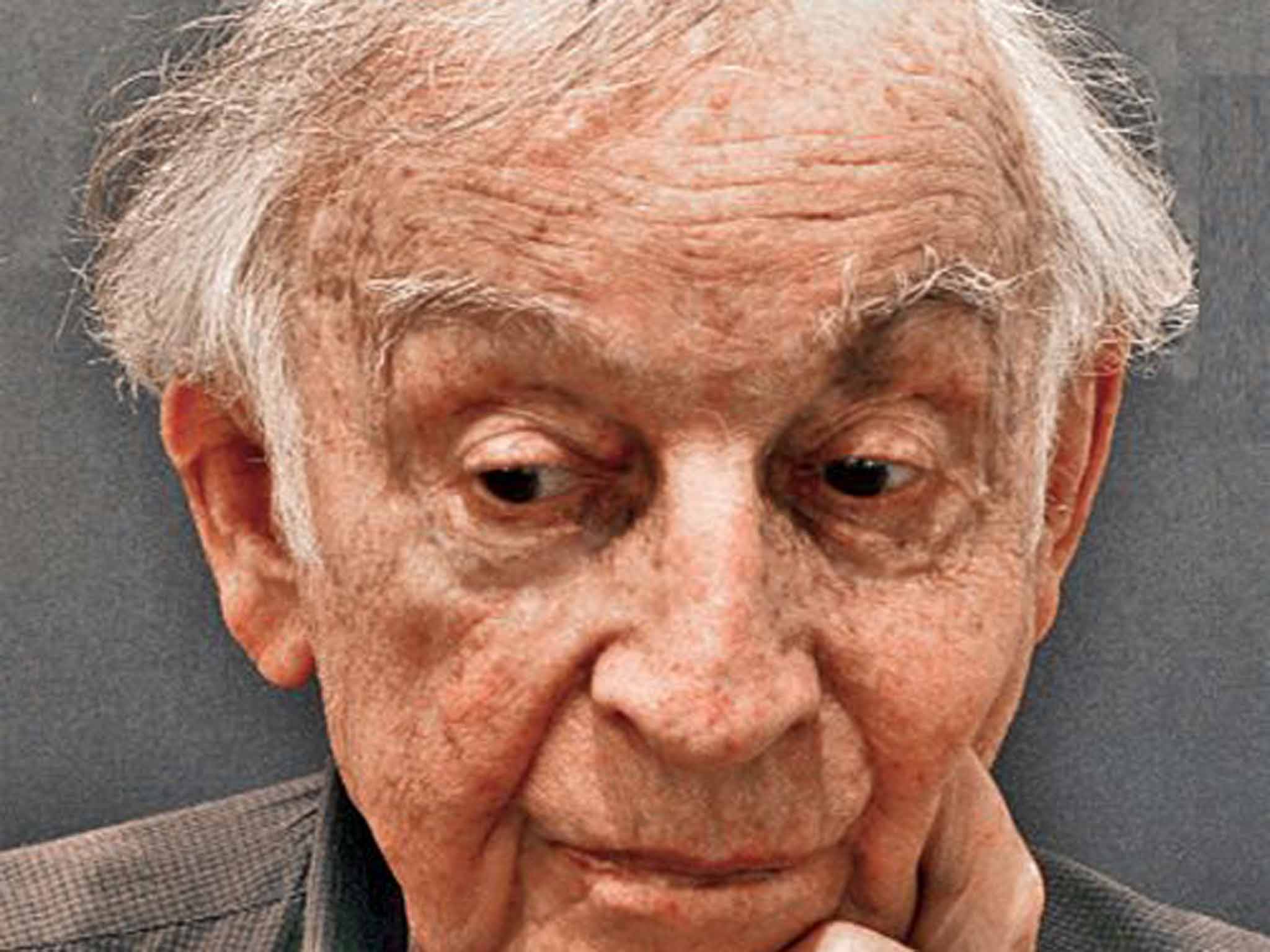

Sidney Mintz: The 'father of food anthropology' who wrote a landmark work on sugar and its part in shaping modern history

In contrast to some anthropologists, he felt that the discipline needed to be grounded in history, and sometimes had political implications

The founder of an entire academic discipline – The New York Times called him “the father of food anthropology” – Sidney Mintz caused academic shockwaves when he linked Britain's sweet-tooth with slavery, the rise of capitalism and imperial expansionism.

Reflecting on his major work of 1985, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History, he said: “I became awed by the power of a single taste, and the concentration of brains, energy, wealth and – most of all, power – that had led to its being supplied to so many, in such stunningly large quantities, and at so terrible a cost in life and suffering.”

In this groundbreaking book, he married the virtues of a careful historian with what he'd learned in his apprenticeship with some of the pioneers of cultural anthropology, especially Ruth Benedict, and wrested the discipline away from those who wanted it confined to the study of aboriginal peoples. “If they don't have blowguns and you can't catch malaria, it's not anthropology,” was a typical Sid quip; for this giant of academe had a wicked sense of humour.

He stated his own approach to the subject on his personal website: “The subject of food or eating habits reveals, as well as anything, the power of culture or cumulative tradition, to shape food behaviour. Because of their capacity for tool use, and eventually for making and controlling fire, humans began to break the links between our animal nature and the food we ate... The foods of different peoples, shaped by habitat and by our history, would become a vivid marker of difference, symbols both of belonging and of being excluded.”

In contrast to some anthropologists, he felt that the discipline needed to be grounded in history, and sometimes had political implications. “My work on sugar, Sweetness and Power, situates it within Western history because [sugar] was an old commodity, basic to the emergence of a global market,” he wrote. “The first time I was in the field I'd been surrounded by it, as I did my fieldwork. That led me to try to trace it backward in time, to learn about its becoming domesticated, and how it spread and gained importance in the growing Western industrial world.”

He viewed the growth of Caribbean sugar plantations in the 17th century, with the slavery needed to work them and the navies to protect them, as the spawn of hunger. “There was no conspiracy at work to wreck the nutrition of the British working class, to turn them into addicts or ruin their teeth,” he wrote in Sweetness and Power. “But the ever-rising consumption of sugar was an artifact of interclass struggles for profit – struggles that eventuated in a world market solution for drug food, as industrial capitalism cut its protectionist losses and expanded a mass market to satisfy proletarian consumers... No wonder the rich and powerful liked it so much.”

Born in Dover, New Jersey, Sid's parents were Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. His father, Solomon, was at first a diemaker, then a clothing salesman, and his mother, Fanny Tulchin, a seamstress who became an organiser for the “Wobblies”, the Industrial Workers of the World (before it was suppressed for being revolutionary, starting in 1917).

Sid had an impeccable foodie pedigree: his father had been a washer-up in a Dover diner, which he bought and then turned into “the only restaurant in the world in which the customer was always wrong.” The business went bust during the Depression, but, said Sid, “Very early on, I became interested in how people acquired, prepared, cooked and served food, and that all came from my father.”

Sid went to Brooklyn College, where he graduated in psychology in 1943, then did war-time military service in the Air Force before entering Columbia as a postgraduate student in anthropology, getting his PhD in 1961.

In 1947 he joined Julian Steward in what he described as a “very daring” fieldwork project in Puerto Rico, studying “the relationship between local social groups and the evolution of their forms of governance.” He later felt that their “overall treatment of island society was skewed by” their failure to confront “analytically the fact the Puerto Rico was a dependent possession, a colony, of the US.”

In 1953, returning to Puerto Rico, “I became the first anthropologist who ever took down the life history of a working man who was a rural proletarian rather than a 'primitive',” resulting in the 1960 publication of the classic Worker in the Cane: A Puerto Rican Life History. It was a deeply humane work, having as much in common with a 19th-century Russian novel as with standard works of anthropology.

He felt that his teaching of undergraduates, especially at Yale, where in 1969 he headed up the first programme of African American Studies, was at least as important as his legion of books and articles. After 25 years at Yale, he left to establish the anthropology department at Johns Hopkins, in Baltimore. His recent work was on soy foods.

In his retirement, Sid wanted to write a book about how his own life changed during the Great Depression: “It was as if the only person I knew for whom the Depression had been good was me. I was too young to be victimised by it, but old enough to work. I grew into adulthood confident about the future.”

Sidney Wilfred Mintz, anthropologist: born Dover, New Jersey, US 16 November 1922; married twice (one son, one daughter); died Plainsboro, New Jersey 27 December 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies