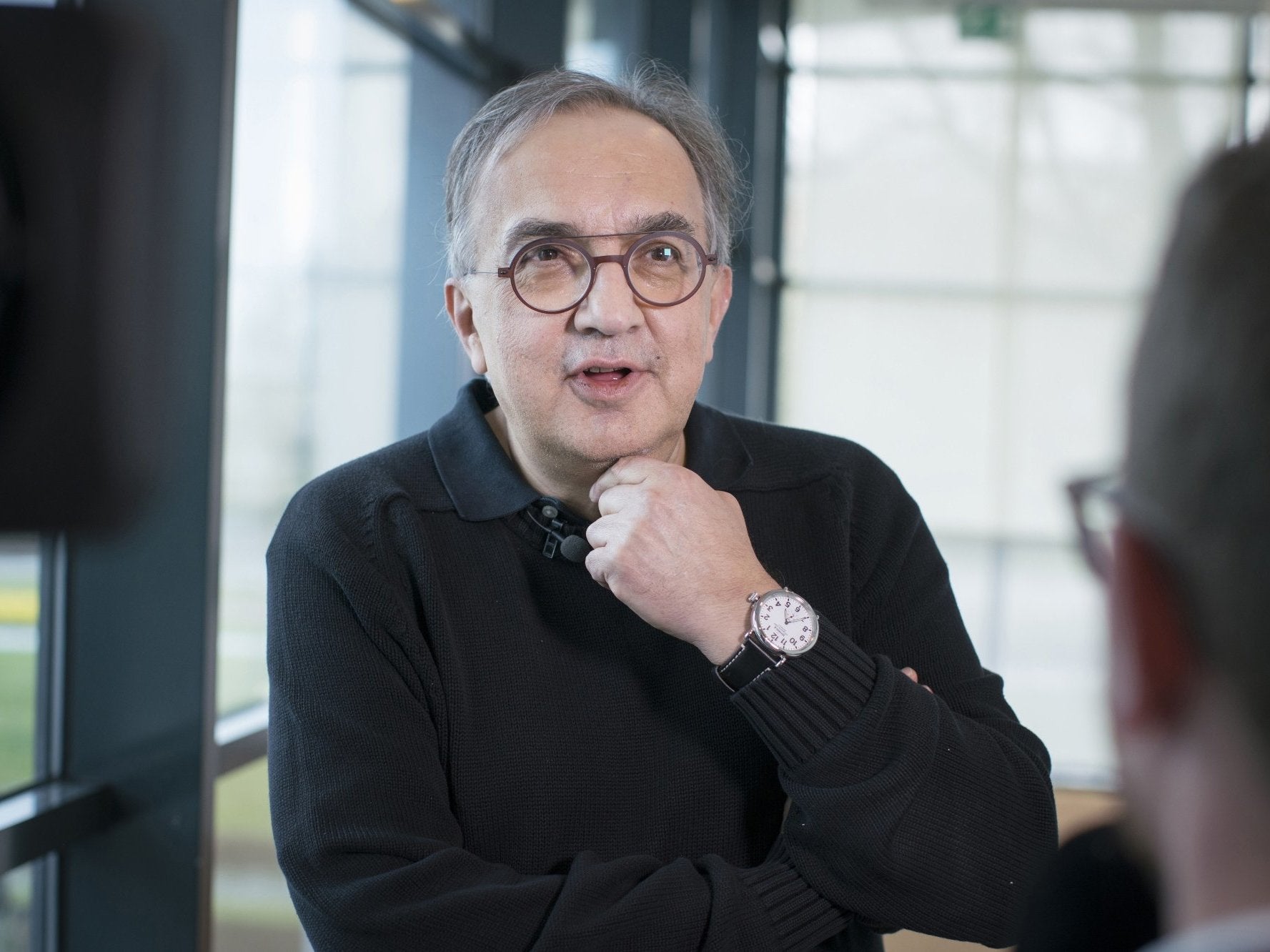

Sergio Marchionne: Italian who steered America’s sputtering Chrysler into a deal with Fiat

Fiat Chrysler became one of the most profitable firms in the car industry in less than a decade under the guidance of the Italian-born, Canadian-raised businessman

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sergio Marchionne was a master negotiator who engineered one of the most brazen automotive deals in history. He persuaded the US government to sell bankrupt carmaker Chrysler to Itay’s Fiat.

Marchionne, who died in Zurich aged 66, then turned the combined Fiat Chrysler into one of the most profitable firms in the industry in less than a decade.

The businessman had already planned to retire next year and turn the reins over to successor Mike Manley, who headed the company’s Jeep and Ram brands.

There appeared to be a sense of frenzied panic about what comes next for the company Marchionne had expanded with astonishing success, much of it credited to his charismatic and frank personality, his negotiating prowess and his indefatigable work ethic.

He also represented a fundamental shift for both Fiat and the wider landscape of Italian industry. He was first person outside the Agnelli clan to be at the helm of Turin-based Fiat and – as the son of an Italian emigrant to Canada – was not groomed within the rarefied cliques that have dominated Italy’s industrial and banking sectors for generations.

The Italian-born, Canadian-raised Marchionne vaulted to instant fame in car industry circles at the peak of the financial crisis in 2009, when he wedged himself into the centre of negotiations in Washington about what to do with failing auto giants General Motors and Chrysler, both on the brink of bankruptcy.

Marchionne became involved with then-president Barack Obama’s “auto task force”, which had the mandate to analyse companies and manage any possible bankruptcies. Marchionne convinced officials that Fiat, which he had run for only five years, was the right partner for Chrysler.

On 30 April, 2009, Chrysler filed for bankruptcy. On 10 June, Fiat and Chrysler announced the merger of the two companies, with Marchionne emerging as chief executive and, in the eyes of many, the saviour of one of Motor City’s legacy companies.

“So the industry looks like its going to sink into oblivion and this fellow who wears this black sweater, chain smokes and drinks gallons of espresso manages to insert himself and convince these people that the best alternative for Chrysler is to merge with Fiat,” said Maryann Keller, a leading automotive industry analyst. “On its own it doesn’t make any sense.”

Marchionne engineered a brilliant deal for Fiat, Keller said.

The initial terms gave Fiat a 20 per cent stake in Chrysler, and the US and Canadian governments, along with the United Auto Workers Union, held the rest. But the Italian carmaker could claim more equity if it met two requirements.

First, the company would have to assemble in North America a small car that would be fuel-efficient at a time of rising gasoline prices. Second, it would have to build a small, fuel-efficient engine on US soil. In exchange, Fiat would get control of Chrysler, free from liability, without paying a dime.

“They gave away the store,” Keller said, adding that the two manufacturing demands put on Fiat were paltry compared to what Fiat got in return: billions of dollars in Chrysler assets and intellectual property.

But speaking to US TV channel CBS’s 60 Minutes in 2012, Marchionne said taking on a failing company was a tall order.

“All these things are long shots – all,” he said. “If it was that easy, then everybody would do it.”

Marchionne found the key ingredients to the relaunch of an automotive giant, starting with a restructuring of the business.

He separated the pickup trucks from the Dodge brand and formed an entirely new pickup line called Ram, whose trucks were marketed for size, engine strength and fast acceleration.

That brand, along with the Dodge line, which he successfully reimagined as the maker of a new American muscle car, took off in the US.

The Jeep brand also thrived under his helm, with international sales giving Fiat Chrysler a footprint in China, the world’s biggest auto market.

Marchionne changed the management structure at Chrysler – a signature tactic he had used throughout his career – and refused to sit in the chairman’s office on the top floor.

“I’m on the floor with all the engineers,” he told 60 Minutes. “I can build a car with all the guys on this floor. That’s all I care about.”

In his 2015 report on the car industry, “Confessions of a Capital Junkie”, Marchionne said consolidation was inevitable. He tried for another merger with General Motors, but the talks never advanced.

“It’s highly unlikely that Chrysler would exist today had he not taken that gamble,” Autotrader.com analyst Michelle Krebs, told AP. “The company was in such bad shape, being stripped of any kind of resources by the previous owners.”

Perhaps Marchionne’s biggest victory was recasting Chrysler in a positive light after its bankruptcy, positioning the company as a gritty, born-from-the-ashes American survivor. A 2011 Super Bowl commercial for Chrysler featured Detroit native and rapper Eminem and the slogan “Imported from Detroit”.

“He captured the attention of the auto market in ways others would be timid about,” Keller said of Marchionne. “He made it cool.”

In June, at what would be his last public appearance as company chairman, Marchionne was in Rome for the presentation of a Jeep to Italy’s Carabinieri.

Marchionne, whose father was a member of the Carabinieri, extolled the values of “seriousness, honesty, sense of duty, discipline and spirit of service”.

Sergio Marchionne was born in Chieti, Italy, on 17 June 1952.

When he was in his early teens, his father moved the family to Toronto to be near relatives and offer his two children more opportunities. Marchionne’s sister, Luciana, died of cancer in 1980.

Assimilation in Canada was not easy at first.

“Trying to get friendly with girls with whom you cannot communicate was a problem,” he told the Globe and Mail.

He received a bachelor’s degree in philosophy in 1978 from the University of Toronto, where he also obtained a bachelor’s degree in commerce the next year. He completed a law degree from Toronto’s York University in 1983 and a master’s degree in business from the University of Windsor in 1985.

Marchionne had two children with his first wife, Orlandina, from whom he was separated. Other survivors include his companion, Manuela Battezzato.

After working as an accountant and tax officer at Deloitte & Touche in Toronto, Marchionne served in executive roles for the Toronto packaging company Lawson Mardon Group and other firms from 1985 to 2000. In 2002, he was named chief executive of a Swiss testing and certification company, and a year later he joined the board of Fiat’s holding company. He later became the holding company’s chief executive and, in 2006, was made chief executive of Fiat’s auto division.

He immediately began a turnaround of the troubled carmaker, cutting costs and whipping it into shape financially. By 2009, he was in Washington, negotiating one of the biggest auto deals of his era. Within two years, Chrysler made its first profit ($183m) since 2005, and paid back its $6bn federal bailout six years before it was due.

“I remember when I came here in 2009,” he said. “There’s nothing worse for a leader than to see fear in people’s faces. It’s been a long, rocky road, but the fear is gone.”

Sergio Marchionne, businessman, born 17 June 1952, died 25 July 2018

Additional reporting by Brian Murphy

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments