Sergei Khrushchev: Soviet leader’s son who became US citizen

‘If Stalin had lived five more years, there is no doubt that we would not be here speaking,’ he once said

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

To many Americans of the 1950s and 1960s, the bald, stocky figure of Nikita Khrushchev was the personification of communism and the Cold War. He was the blunt leader of the Soviet Union who, when hostilities were on the rise in 1956, addressed a gathering of western diplomats with some of the most ominous and threatening words of the era: “Whether you like it or not, history is on our side. We will bury you.”

The statement was described by Soviet interpreter Viktor Sukhodrev as an “exact translation” of Khrushchev’s words.

Years later, Khrushchev’s son, Sergei, tried to explain: “He meant that capitalism would die and that the Soviet economic system would bury it. But my father was a part of the Cold War, a war of propaganda, and so these words were used against him and misunderstood by Americans.”

Sergei Khrushchev, who was a top Soviet expert on guided missile design, often accompanied his father on diplomatic missions around the world. Eventually, however, he grew disillusioned with the communist system, which he said “is not effective in any society”, and settled in the United States.

He died on 18 June in Cranston, Rhode Island, at 84. The cause of death was a gunshot wound to the head, said Joseph Wendelken, a spokesperson for the state medical examiner’s office. Cranston police told the local paper Providence Journal there was no evidence of foul play.

Khrushchev came to the United States as a visiting scholar at Brown University in 1991, the year the Soviet Union was breaking apart. He was not technically a defector, but his name and his close resemblance to his father made him a subject of eternal curiosity, as he gave speeches throughout the country.

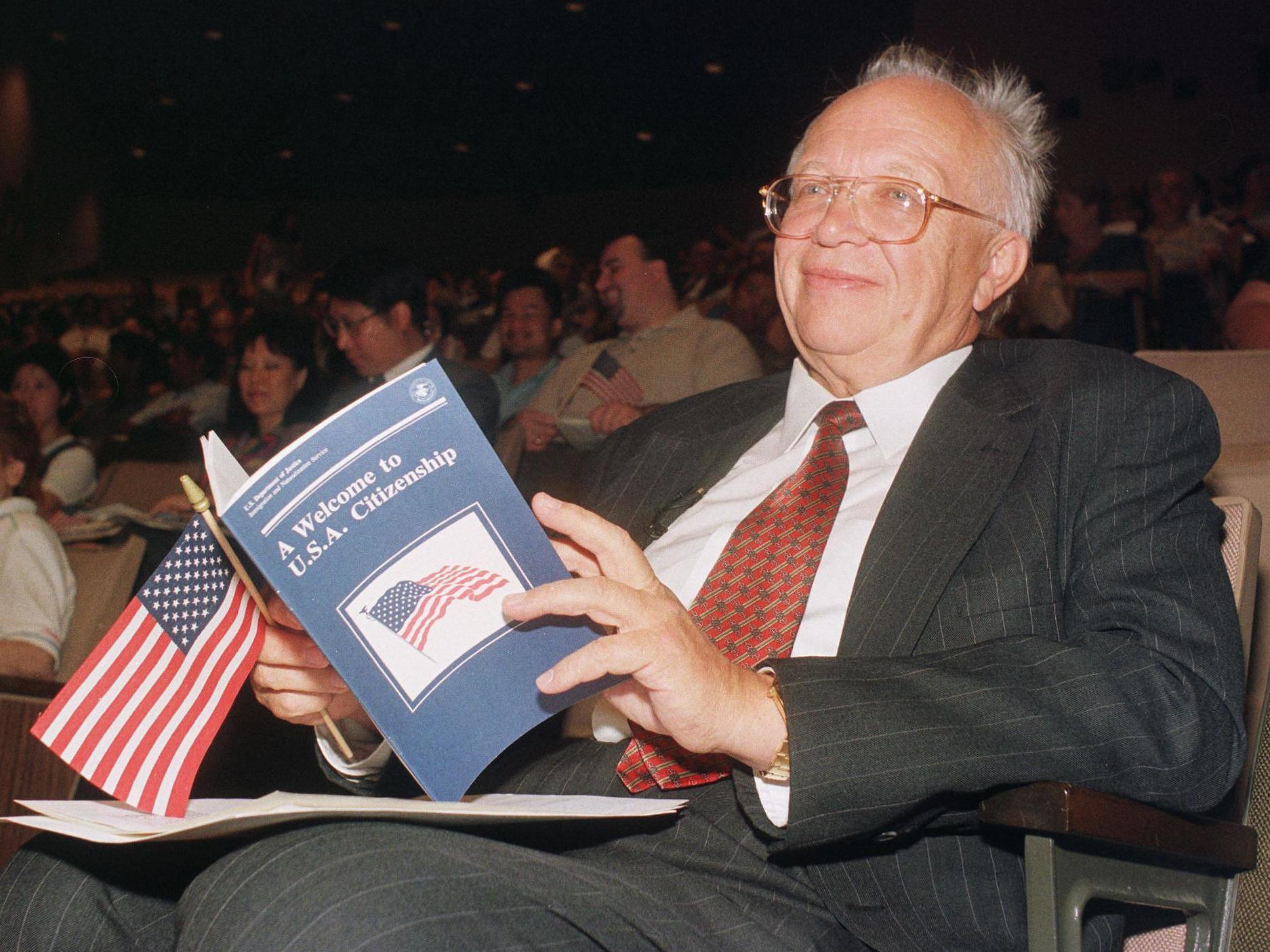

Even as he became a naturalised US citizen, Khrushchev remained a staunch defender of his father, who succeeded Joseph Stalin as premier of the Soviet Union in 1953.

In 1959, Sergei Khrushchev joined his father on a visit to the United States and made home movies of things unknown in the Soviet Union: motorcycle police, billboards, Times Square.

“We would look into the faces,” he told the Chicago Sun-Times in 1999. “We decided that the message was that these people would not want to attack us at home. They did not want war. They were content, and seemed satisfied to be getting rich.”

Khrushchev was also with his father during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, when the two superpowers narrowly averted a showdown after the Soviet Union placed nuclear missiles in Cuba. President John F Kennedy saw the move as a clear provocation and directed US warships to sail towards Cuba.

Despite misunderstandings on both sides, Kennedy and Khrushchev were able to negotiate a resolution that avoided outright war.

“[My father] told me, ‘I trust the American president’,” Sergei Khrushchev told the Baltimore Sun in 1999. “‘I think he’s [an] honest man.’”

After Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, Nikita Khrushchev sent a diplomatic delegation to the president’s funeral and had his wife convey personal condolences to first lady Jacqueline Kennedy. The overtures were seen as good-faith efforts to reduce tensions between the two countries.

In 1964, the 70-year-old Nikita Khrushchev was summoned to the Kremlin for what was described as an important meeting about agriculture. Instead, other Communist Party officials forced him from power. Khrushchev did not fight the move and became the first Soviet leader to leave office while still alive.

He returned home and told his family: “It’s over. I’m retired.”

Khrushchev remained under surveillance until his death in 1971. During those years, Sergei Khrushchev took long walks with his father and helped him write his memoirs, which were published years later.

“He was in the Communist Party because he believed it would be best for all of us,” Sergei Khrushchev told the Sun-Times. “If, like me, he had seen that capitalism ended up working better, maybe he would have come to America, too.”

Sergei Nikitich Khrushchev was born on 2 July 1935, in Moscow. He was one of six children.

His father, who had peasant roots in Ukraine, was a rising official in the Communist Party and managed to evade Stalin’s wrath.

“If Stalin had lived five more years, there is no doubt that we would not be here speaking,” Sergei Khrushchev told the Sun-Times. “You could not just be fired from the job. You would be eliminated. And so would your family.”

He attended what is now the Moscow Power Engineering Institute, receiving a doctorate in 1961. Khrushchev became director of the Soviet missile design bureau and later was the research director of a computer institute.

After the thaw in the Cold War ushered in by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in the 1980s, followed by the eventual dissolution of the Soviet Union, Khrushchev came to Brown University for a one-year term as a visiting scholar at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs.

He applied for permanent US residency, with letters of support from former presidents Richard Nixon and George HW Bush and former defence secretary Robert McNamara. Khrushchev and his wife, Valentina Golenko, became naturalised US citizens in 1999.

His three sons from an earlier marriage to Galina Shumova stayed in Russia. One son, Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev, died in 2007. Survivors include Golenko, whom Khrushchev married in 1985, and two sons from his first marriage. A complete list of survivors could not be confirmed.

Khrushchev wrote several books about his father and Russian society and lectured throughout the United States, from universities to the CIA to rural forums in Montana. In recent years, he was increasingly concerned about the future of Russia under the rule of Vladimir Putin.

“The foundation of a democracy is law,” he said in 2017. “There are many questions to whether that’s being upheld in Russia right now.”

At home in Rhode Island, Khrushchev became a devoted gardener and household carpenter, building a Russian-style steam bath in his basement. He drove a Buick, shopped at Home Depot and enjoyed casual encounters with his new countrymen.

“Americans are very friendly,” he told the Sun-Times. “If you ask for directions in the street, they do not turn and hurry away, as if afraid, but show you right to where you want to go.

“And in Russia, all the computers are falling apart. Here, they work.”

Sergei Khrushchev, engineer, born 2 July 1935, died 18 June 2020

© The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments