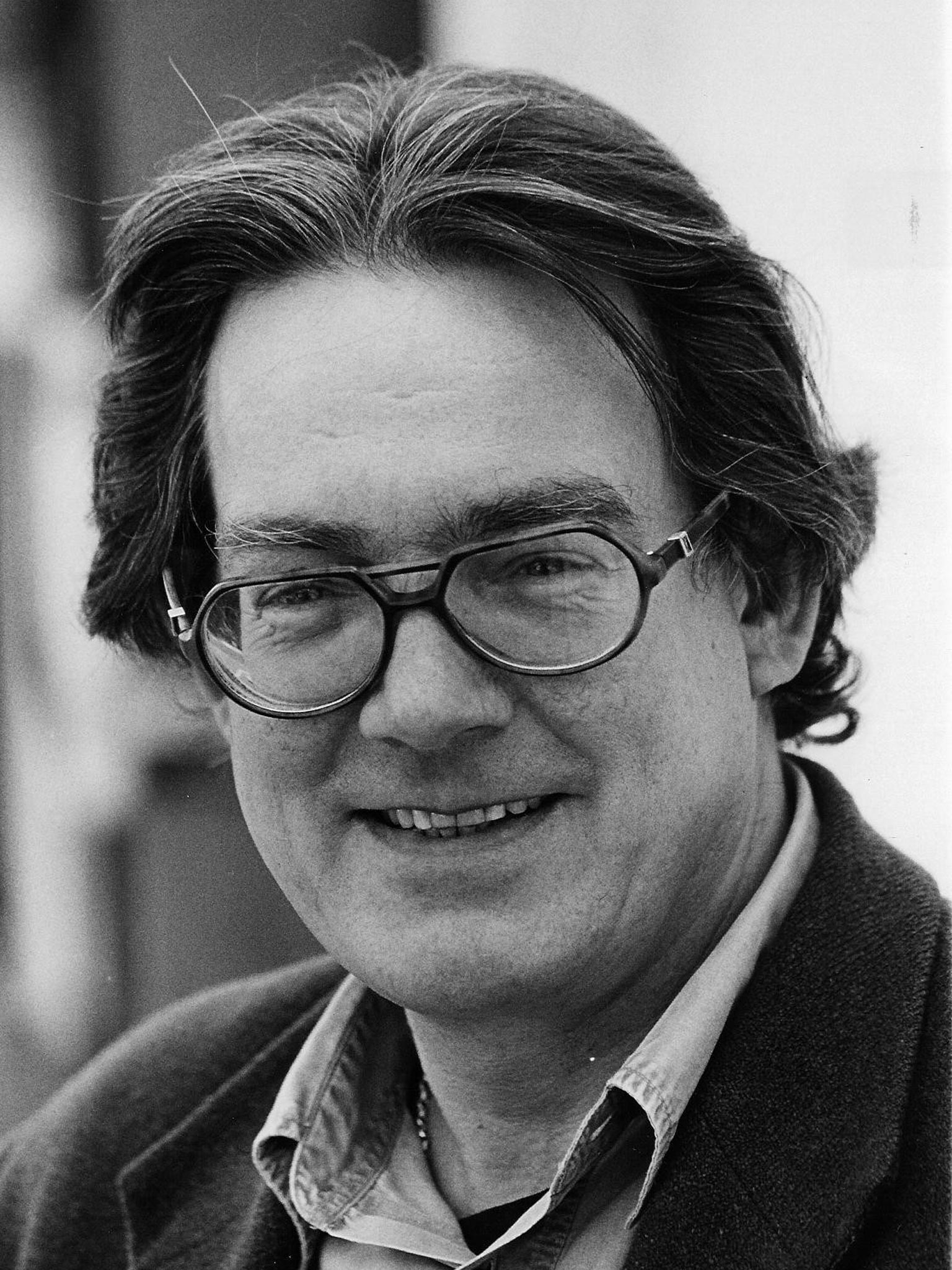

Sebastian Barker: Poet born into a literary dynasty whose own distinctive voice was inspired by a sense of place

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.To speak of a life ending on a note of triumph sounds a little odd. And yet this was the case with the poet Sebastian Barker, who died of a cardiac arrest at the age of 68 within a day and a half of participating in a reading in celebration of the publication of Land of Gold, his new book of poetry, in Trinity College Chapel, Cambridge. That night, whether reading his own poems or answering questions fired from the choir stalls by friends and relatives about how and why poems get written, he had seemed –and sounded – astonishingly robust, confident, fearlessly exuberant, and future-facing, in spite of the fact that almost all who were listening knew that he was suffering from untreatable lung cancer.

One of his three daughters, hearing a passing reference to herself in a poem, questioned him, so movingly, about how thought relates to feeling in poetry. The most poignant and painful moment, as it turned out, came when he read "The Ballad of Regrets", in which he itemised all those cherished things of life which will need to be abandoned when death comes calling.

Sebastian Barker emerged from a famous literary dynasty. His father George Barker was an important poet from the 1930s, and a notorious roustabout into the bargain: Sebastian remembers as a small boy in London romping behind the bar at Muriel Belcher's Colony Club in Lexington Street, Soho. His mother, Elizabeth Smart, was best known for the small-scale literary classic By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept.

Poetry was in the blood from first to last, and he was was at the centre of the poetry – and the literary– life of London for decades. He chaired the Poetry Society, edited The London Magazine, organised readings, and was an extraordinarily generous encourager of the talents of others. One of the most dramatic events in his own life took place at the age of 52, when he was baptised; his Roman Catholic faith was a great source of sustenance and succour to the end. What is more, it ramified into all areas of his life. In later life he also wrote books on theological matters.

Sebastian had at least two selves. One of them was an Englishman, who as a child had lived at Tilty Mill near Great Dunmow in Essex – he was to revisit that dilapidated place, at the suggestion of his wife, the poet Hilary Davies, the day before his death; another self was Greek, by adoption. He bought a ruin in the village of Sitochori, towards the Turkish border, in 1983 and, little by little, rebuilt it in the traditional style, with the help of local people. The place became his home-from-home for almost 30 years, and the influence of the poetry of the Nobel prizewinning Greek poet Odysseus Elytis, particularly his use of the long line, had a profound impact upon his late writings.

Sebastian's late sequence A Monastery of Light (2013) is a kind of distillation of all that he had thought and felt about the spirit of that set-apart place, and the way he describes its writing in a headnote to that long, teeming, multi-part poem, tells us a great deal about how he wrote, and what poetry meant to him, life-long. Poetry, Sebastian believed, was a gift from the gods, and it was to be seized with both hands when proffered. This was certainly the case with this late sequence, which circles about his adopted village. When the words came, it felt like the spirit talking. As he explained in Cambridge, the experience was terrifying, unnerving and unstoppable – like a hire car that threatens to swing out of control as it threads its way along twisty mountainous tracks. The key point is that the spirit is not be ignored. It may never come again.

I first heard Sebastian read at the Poetry Society in Earl's Court, west London, in the 1980s. In a leather jacket, and with shoulder-length hair, he looked a little like Jim Morrison in those days. What struck me then was the intensity of the reading voice, the rapt look in the eye. Poetry, as for that great master of human psychology William Blake (who was at his shoulder from first to last) was a sacred matter for Sebastian, and the whole of human life, the fleshly and the spiritual, was bathed in that same aura of sacredness. Like Blake, Sebastian had the ability to write lyric poetry which used simple words to encapsulate profound meanings.

After the reading in Trinity Chapel, friends and family celebrated in a nearby local restaurant. Sebastian, perky in his wheelchair, was as warm, good-humoured and generous-spirited as ever. Just before I left to take the train back to London, I walked over to his place at the centre of the long table – there must have been 15 of us around it – to say goodbye. He kissed me, laughing, and gave me one of his rough, fierce, no-holds-barred embraces. Then he raised his glass of favourite red. Always red. Always his favourite.

Sebastian Barker, poet: born 16 April 1945; one marriage dissolved (one son, three daughters); married Hilary Davies; died, 31 January 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments