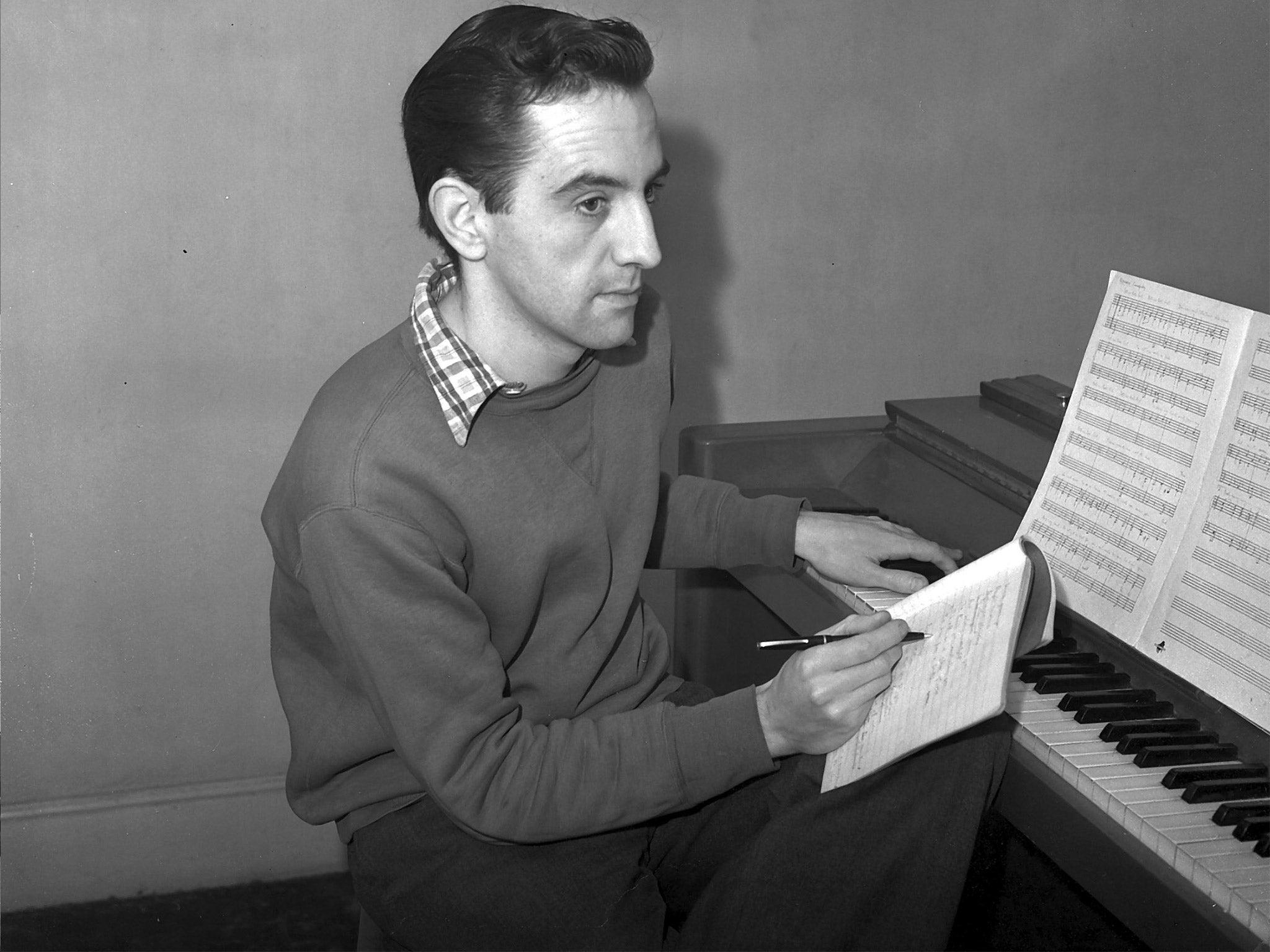

Sandy Wilson: Lyricist and composer best known for the musical 'The Boyfriend', which had great success on stage and screen

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Wedded to his musical The Boyfriend, whose script he wrote – for £25 down and £25 on completion of its short run – in a matter of mere days, practically without alterations, followed by the lyrics and music "with almost as equal ease", Sandy Wilson was far more than purveyor of the frothy "postwar valentine" which the show appears to represent. In reality he was a reluctant rebel affecting to be insouciant.

He was, like his friend Noël Coward, "born with a talent to amuse", but he was passionate and angry, too. The disguise suited Wilson fine. He was a hugely sensitive man, tolerant and kind, unless you annoyed him, whereupon he'd go cold. Private and secretive, he lived most of his life behind a thick plate glass of deflection which said, "don't enquire."

His autobiography (1975) entitled I Could Be Happy after one of the catchiest tunes from The Boyfriend, is a scintillating but strictly surface account of the growing pains of the show which has been nascent to an international industry. The show made Wilson rich, which did little to appease his intensely galling feeling of never having much success with his other work. Divorce Me, Darling! (1964) continued the story where The Boyfriend left off, but had no success. Nor did any other of Wilson's shows, including a brilliantly crafted adaptation of Ronald Firbank's erotic novel Valmouth (1958; revival, Chichester, 1982), the legacy of which was Wilson's fine country house in Somerset that bears its name.

Wilson's life was conflicted between the need to be free, to move, travel and think, and feeling trapped by the inordinate success of The Boyfriend, which he guarded jealously like it was a real boyfriend – which in a way it was, although for him it probably constituted a representation of his mother, for whom he held a close and virtually textbook attachment.

He was born in 1924 in Sale, as "a result of a moonlight picnic" following parental separation and a highly charged reconciliation when his mother was 43. He had three elder sisters and his birth was foretold by an Indian fortune teller to their mother – "she was fascinated by the occult" – for whom he was her "dreamchild". She was a Londoner, "gay, imaginative and wilful", whereas his father, a remote figure who died relatively young in 1938 from pleurisy, was "a sober countryman possessed of a strong Presbyterian sense of duty."

The family's Raj background, bolstered by a fortune made in the woollen mills of Bannockburn, gave way to reduced and ever-diminishing circumstances. Wilson was virtually compelled to gain the top scholarship to Harrow and then to Oxford, where he engaged with every theatrical activity he could (including befriending Hermione Gingold, who he maintained had "more talent than anyone I ever knew").

This was after three years in the army, narrowly failing to get a transfer into Ensa. At Oxford he had nobody to please but himself, studying English literature over Latin and Greek. "'BA Oxon'," he said, "has made not the slightest difference to my career; but everything else about it had a profound influence on the rest of my life". He took a course in production at the Old Vic School.

By degrees of chance and sheer tenacity, Wilson's break came when asked to write The Boyfriend, first as a one-hour one-acter for the New Watergate Theatre. Its transfer, expanded, to The Players Theatre and its subsequent success – all tickets were sold out, and on transferring again to Wyndhams in 1954 it ran for 2,084 performances – was not easily attained.

By the time Broadway beckoned Wilson was in the groove of expecting productions to run precisely according to the affectionate spirit wherein the show had been created, under no circumstances to be tampered with. Broadway changed that. His long-time producer and surrogate mother, Vida Hope, was fired and he was barred from rehearsals. By the time he was allowed to see the first show (with Julie Andrews on her way to becoming a star) he was "numb with anger, distress, fear and frustration."

In Ken Russell's film version (1972), the changes were more severe and Wilson's distress was commensurate. Years later Trevor Nunn wanted to bring the show to the National, and in a interview with the author plied him with taking it into the West End and Broadway, but he also explained what seemingly endless changes he would make. It was fatal. After a pause, Wilson spoke with a half-smile: "I've done all that already, and no, you're not [making changes]." Nunn exploded: "Why have I been sitting here for three hours, then?"

Wilson always wanted The Boyfriend to be seen by the world in the right way, which meant keeping strictly to his words, directions and certain encoded devices, without which productions of it seem to fail. What The Boyfriend really represented and why it succeeded may not have been clear even to him: the tender human yearning for union beneath a surface of 1920s delicacy that makes it something timeless, not just a period piece of confection.

At the Open Air Theatre, Regent's Park, two recent productions met critical acclaim, not least from the author. The second, in 2007, was sad for Wilson, who realised he was seeing it in London for the last time. He was most pleased, however, because of the audience's diversity, particularly the young. "I loved sitting there in the auditorium," he said, "I basked in it."

During rehearsals with the director Ian Talbot he made it plain who held the reins: "Look!" he said, "Gershwin is dead, Cole Porter is dead, but I am still alive!" and he furiously proclaimed: "How dare you!" when Talbot came to play Lord Brockhurst. Talbot was one of the best Lord Brockhursts ever, and Wilson later sent him the biggest fan letter imaginable.

Wilson's ritual, like Coward's, following a run-through, was, first, lunch on a white tablecloth with dry white wine: "And now the notes…" he would intone, at which point the stalwart Chuck, whom he married in a civil ceremony, would discreetly withdraw. When this occurred in 2007 at Regents Park a bubble machine operating for a children's matinee of The Adventures of Mister Fox went into action. Gradually the bubbles frothed up around the octogenarian. Wilson seemed to be oblivious as bubbles and children floated waist-high around him. Fascinated, Talbot interrupted the note-giving: "Wilson, do you see what's happening?" Came the reply, "Yes. It's rather charming." That was the man.

JULIAN MACHIN

Alexander Galbraith Wilson, composer and lyricist: born Sale 19 May 1924; died 27 August 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments