Sally Menke: Film editor whose cutting style was a crucial element in the work of Quentin Tarantino

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

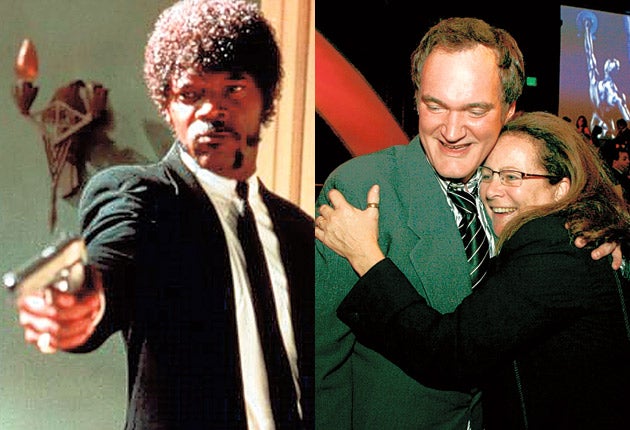

Your support makes all the difference.Quentin Tarantino is one of today's most distinctive directors, but his films' complex structures and witty montages were the result of his work with the editor Sally Menke, whose 20 or so credits include all of his films. He, in turn, recognised her as his "only true, genuine collaborator".

Menke's mother was a teacher and her father a professor of management. In 1977 she graduated from the New York University Tisch School ofthe Arts' film course. Film editors are often women and Menke was particularly inspired by Thelma Schoonmaker, who works with MartinScorsese. Menke joined CBS, working on documentaries. A few years later she had her first (inauspicious) movie credit, Cold Feet (1983), a romcom about two unhappy solipsistic Manhattan couples.

In 1985 Menke edited – and sound- edited – a 10-minute black-and-white short by fellow Tisch alumnus Dean Parisot: in Tom Goes to the Bar an opinion pollster contemplates his life while hanging, batlike, from the ceiling of a bar filled with strange customers. The following year Menke and Parisot married. Back at CBS she edited The Vanishing Family: Crisis in Black America (1986) and, for PBS, Ken Burns' The Congress (1988), telling the story of that institution through interviews and archive footage.

Her Hollywood break came with Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (1990). Though it was conventionally structured, its high-octane fight sequences were very effective. Menke had heard that tiro director Quentin Tarantino was looking for a good, cheap editor, and she got in touch. He sent her the script of Reservoir Dogs (1992). She thought it was "amazing" and determined to join the crew.

As well as deciding exactly where to make a particular cut, editors are instrumental in setting a film's larger structure. Tarantino's films, with their complex chronologies, plots and subplots, need an editor who can make sense of that welter of information. Menke was that editor. They developed a style of dialogue-driven, roving-camera, slow-cut scenes interwoven with fast-cut action scenes. "We just clicked creatively," Menke remembered. "Editing is all about intuiting the tone of a scene and you have to chime with the director... We've built up such trust that now he gives me the dailies and I put 'em together and there's little interference."

The dance sequence in Pulp Fiction (1994) similarly slowed the storydown after a rapid sequence, intensifying Uma Thurman and John Travolta's deepening relationship. ToddMcCarty of Variety described her editing as "the definition of precision." Unsurprisingly, she picked up an Oscar nomination.

Oddly, Menke didn't cut to Tarantino's signature music tracks: "I just make the scene work emotionally and dramatically, and then Quentin will come in and lay the track over it and we'll tweak it to the beats."

But Tarantino's enthusiasms made his films increasingly unwieldy. Kill Bill expanded into a two-parter (2003 and 2004). It drew on both kung fu and spaghetti Westerns, but Menke observed, "Our style is to mimic, not homage, but it's all about recontextualising the film language to make it fresh within the new genre. It's incredibly detailed." Even the popular press noticed Menke's work. The New York Times' Elvis Mitchell recognised the contribution her "deft fingers" made to Kill Bill: Vol. 2's "wheel-in-a-wheel tricksiness."

Death Proof (2007) was initially harnessed to Robert Rodriguez's Planet Terror in the double-bill Grindhouse. But it bombed and they were unshackled. Tarantino decided to lengthen his film to 114 minutes, climaxing with a long, exciting car chase.

After these stylistic excesses, the long-gestating Inglourious Basterds (2009) was occasionally more restrained. Menke pointed to the opening: "It's all about tension, so you follow the emotional arc of a character through a scene, even if... they're just pouring a glass of milk or stuffing their pipe. We're very proud of that scene – it might be the best thing we've ever done." She was rewarded with another Oscar nomination.

The collaboration with Tarantino was undoubtedly the major strand in Menke's career: the only other director with whom she worked more than once was Billy Bob Thornton, on All the Pretty Horses (2000) and Daddy and Them (2001). She also edited Heaven & Earth (1993), the epic final panel of Oliver Stone's Vietnam trilogy. Ole Bornedal's Nightwatch (1997) didn't match his Danish original version, but Mulholland Falls (1996), a 1950s-set noir directed by Lee Tamahori, was effective. Her last project was Peacock (2010), an examination of a rural bank clerk's secret life.

However, such was their working bond that she worked with Tarantino through both pregnancies and checked his schedule before accepting other assignments to ensure that she would be free for him. He showed his affection by filming cast members' greetings for her to enjoy in the daily rushes. These "Hi Sally" reels turn up as extras on some of the DVDs. Beyond the tragedy of her death, it is a schismatic moment in Tarantino's career as he plans Kill Bill: Vol. 3, which she certainly would have edited.

Menke was a regular hiker (she was holidaying in Canada when she learned that she'd got Reservoir Dogs) and on 27 September she headed for the Hollywood Hills. At 113 degrees, it was the hottest day since 1877 and it seems she succumbed to hyperthermia.

John Riley

Sally JoAnne Menke, film editor: born Mineola, New York 17 December 1953; married 1986 Dean Parisot (one son, one daughter); died Los Angeles 27 September 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments