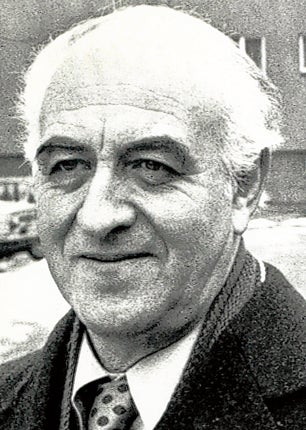

Rudolf Barshai: Viola player and conductor whose career continued to flourish after exile from the Soviet Union

Rudolf Barshai was one of the last surviving members of the cohort of great Russian musicians who came to prominence in the middle of the last century, among them Gilels, Oistrakh, Richter and Rostropovich. Barshai will be remembered chiefly as a conductor, but he first made his mark as a violist, and for two decades was as predominant a player as Yuri Bashmet in more recent times.

Barshai was born in the village of Stanitsa Labinskaya (today Labinsk), in the Krasnodar region northwest of the Georgian border. Having got through a seven-year music course in only two, he enrolled at the Moscow Conservatoire in 1938; there he studied violin with Lev Zeitlin (making him a "grand-student" of Leopold Auer), conducting with Ilya Musin and composition with Dmitry Shostakovich.

It was Barshai's desire to establish a string quartet that led him to the viola: he could not find the player he wanted for the group and so picked up the instrument himself, taking instruction from Vadim Borisovsky, who raised the stature of the viola in the USSR rather as Lionel Tertis did in Britain.

When the Moscow Philharmonic Quartet made its debut in 1945, its members – all students of Mikhail Terian, the violist of the Komitas Quartet – were Rostislav Dubinsky and Nina Barshai, Rudolf's first wife, as first and second violin, with Barshai the violist and the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich – who left after only two weeks, to be replaced by Valentin Berlinsky, who remained for 60 years.

Shostakovich formed an early relationship with the Quartet, coaching them in his string quartets – only three by 1946 – and partnering them in his Piano Quintet, then still in manuscript. At rehearsal one day Barshai misjudged an entry and came in a fraction too late. Shostakovich's reaction was typically generous: jumping up from the piano, he said "Please, keep it like that", and so the score was amended.

By 1953 the Quartet enjoyed such national standing that it played at the funerals of both Stalin and, later on the same day, Prokofiev, both of whom had died on 5 March. The musicians were shunted between the ceremonies in an ambulance – but neither engagement was paid. Now Nina and then, in 1954, Rudolf left the Quartet, which took on the moniker of the Borodin Quartet. Rudolf – newly married to his second wife, the painter and costume-designer Anna Martinson, daughter of a famous Russian comic, Sergei Martinson – joined the Tchaikovsky Quartet, whose leader was Yulian Sitkovetsky (father of the violinist and conductor Dmitry). This new ensemble was not to last: in 1956 Sitkovetsky was diagnosed with lung cancer and died only two years later, aged 32.

By then Barshai was active as a conductor, having founded the Moscow Chamber Orchestra in 1955, acting at its head as long as he remained in the Soviet Union. Its repertoire stretched back to the Baroque – unfamiliar in Russia at the time – and forward to Barshai's contemporaries. Mieczyslaw Weinberg was one: his Second Sinfonietta and Seventh and Tenth Symphonies were written for Barshai; so, too, was Boris Tchaikovsky's Chamber Symphony. The biggest feather in his cap was the premiere, in Leningrad in September 1969, of Shostakovich's Fourteenth Symphony. The MCO, said Shostakovich, was "the greatest chamber orchestra in the world".

When the Soviet authorities permitted, Barshai toured with his orchestra. Their first visit to Britain came in 1962, on which occasion he recorded the Mozart Sinfonia concertante for violin, viola and orchestra, with Yehudi Menuhin the other soloist. On that visit the MCO joined the Bath Festival Orchestra that Menuhin had founded in a performance and esteemed recording of Tippett's Concerto for Double String Orchestra.

But Barshai was Jewish, and semi-official anti-Semitism repeatedly reared its ugly head. Goskonzert, the state concert agency, would receive requests for Barshai to conduct abroad and turn them down without consulting him; on other occasions he was not permitted to join the MCO on tour abroad. The KGB even went as far as poisoning his third marriage, to Teruko Soda, a Japanese translator, feeding her rumour while he was away.

Soviet artists, Barshai complained, were like pieces on a chessboard, unable to control their own destiny, and he applied for permission to spend a year working abroad. The authorities forced his hand, refusing him permission to go unless he left the country altogether. And so he did, emigrating to Israel in 1976. He then became a non-person in the USSR: all mention of him vanished, even from his own recordings. Shostakovich had intended to dedicate his last work, the Viola Sonata, to Barshai – but the composer's death in 1975 and Barshai's emigration the next year meant that the dedication and the privilege of the first performance went instead to Fyodor Druzhinin.

In the west Barshai's star continued to shine. He worked with the Israel Chamber Orchestra, serving as chief conductor until 1981, and then from 1982 to 1988 with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; for three years from 1982 he was music director of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. He also guest-conducted the London Philharmonic. He settled in Switzerland, where in 1999 a Camerata Rudolf Barshai was founded; Barshai, naturally, was asked to conduct it.

Relations with his western musicians weren't always harmonious – the German writer Bernd Feuchtner, who worked with Barshai on his (still unpublished) memoirs, found that in rehearsals "he could be quite brusque throughout: he was of the old school, but it was always delivered in a friendly tone – and he was always right! Everything that was external, decoration, show, was anathema to him; he was direct and simple". Barshai was, Feuchtner recalled, "like all really great artists, a modest man, who never made any fuss about himself. He was music through and through".

With Kyrill Kondrashin Barshai had been one of the two conductors responsible for presenting Mahler's music to Soviet audiences, and in 1993, after the fall of the USSR, he returned in triumph for a series of concerts, one featuring the Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra in the Ninth Symphony, a performance released by the Swedish label BIS. Many other Barshai recordings were fêted by the critics, chief among them his cycle of the 15 Shostakovich symphonies with the West German Radio Orchestra (on Brilliant Classics).

Barshai's arrangement of Shostakovich's Eighth String Quartet as a chamber symphony for strings had earned its composer's enthusiastic endorsement, and in later years he went on to arrange the Third, Fourth and Tenth Quartets in the same way, as also the piano suite Visions fugitives by Prokofiev, with whom he had enjoyed long discussions about orchestration. In 2000 he completed the scoring of Mahler's unfinished Tenth Symphony, which he recorded in 2004; a year earlier he prepared a string-orchestra version of the Ravel String Quartet for the Scottish Ensemble. In his days with the Moscow Chamber Orchestra he had arranged and recorded Bach's Musical Offering and Art of Fugue, and he revised the latter, completing it in the teeth of ill health days before his death.

Three of Barshai's four marriages had produced a son, and he was a caring father: though his three children were spread across the globe, his touring allowed him to see them frequently. His fourth marriage, to the organist and harpsichordist Elena Raskova, lasted over 40 years, and they often welcomed visiting musicians to their house in the Swiss mountains.

Martin Anderson

Rudolf Borisovich Barshai, violist and conductor: born Stanitsa Labinskaya, Krasnodar region; married firstly Nina Markova (one son; marriage dissolved), 1954 Anna Martinson (one son; marriage dissolved 1963), thirdly Teruko Soda (one son; marriage dissolved), fourthly Elena Raskova; died Basel 2 November 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments