Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ron Lyle was an élite member of the fighting brotherhood of American heavyweights from the 1970s that included Muhammad Ali, Ken Norton, George Foreman, Jerry Quarry, Joe Frazier and Earnie Shavers. Lyle, however, was the most fearsome of the gifted sluggers, with two known murders on his arrest sheet, a signed death certificate from a prison stabbing and a brutal reputation. He was also, as his brilliant biographer Candace Toft has written, a "soft-spoken and gentle man".

In 1971, after serving nearly eight years for a killing, Lyle finally turned professional. He was 30 years ofage and his years in prison had included several near-death encounters, including a savage assault that left him with knife wounds to his stomach, which then required a massive blood transfusion. It was at this darkest of hours that a death certificate was prematurely signed; Lyle still had some fighting to do.

After being released in 1969 he boxed as an amateur, beating a Russian in the once essential-viewing duel between the two great Cold War rivals; he had crazy dreams of the Olympics. He also knocked out Duane Bobick, who was unconscious for five minutes. Bobick did make the Olympic squad and was beaten by the Cuban gold medallist Teofilo Stevenson. "I could have beaten Stevenson, I know I could," said Lyle, but he turned professional 17 months before the Munich Olympics.

After 19 fights in less than two years Lyle lost for the first time when Quarry, arguably the best white heavyweight in the last 60 years, beat him on points. Ron Lyle, convict, Olympic dreamer and killer, was with the sport's big boys and he would stay at that level from 1973 until 1977 in extraordinary fights against Foreman, Shavers and one against Ali for the world heavyweight title. He fought the trio over a six-month period, which now seems barely believable.

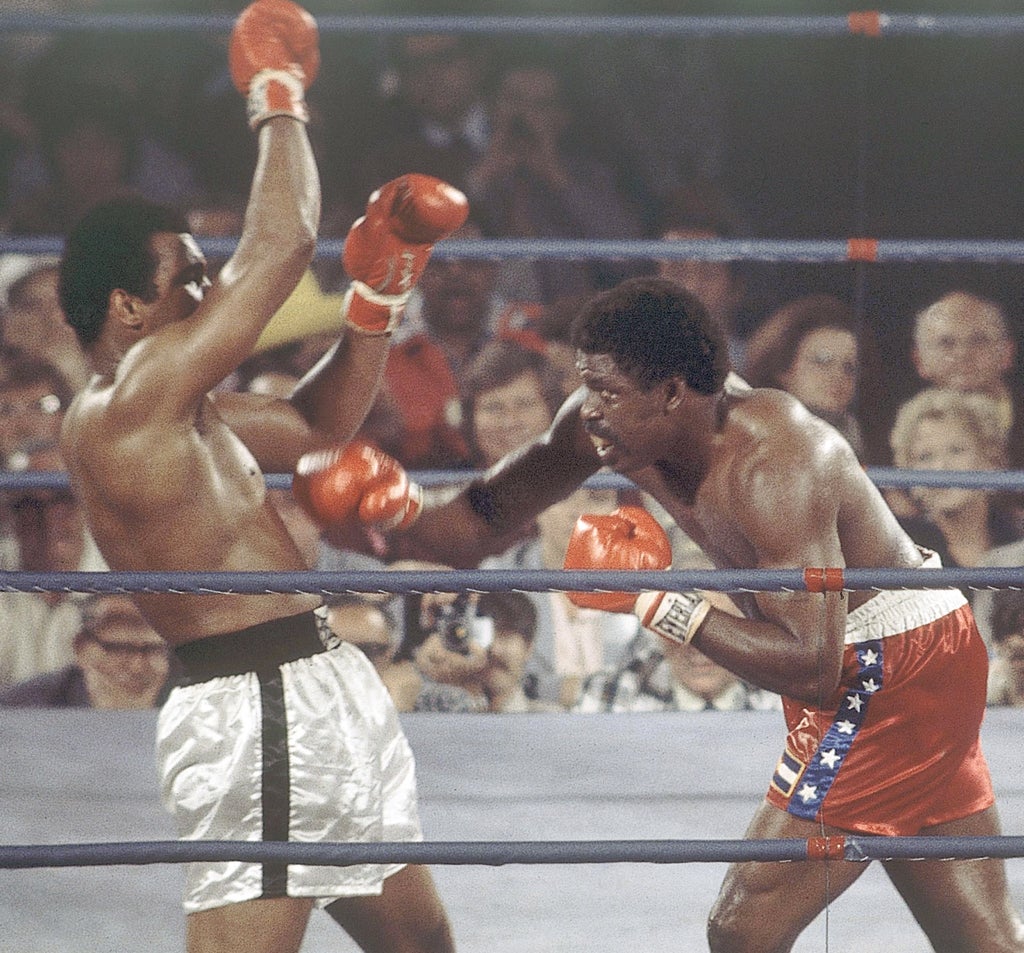

Against Ali in Las Vegas in 1975 for the title, Lyle was leading on two of the scorecards and drawing on the third after 10 rounds. But in the 11th Ali had Lyle out on his feet and was calling in the referee, who stood his ground, as did Lyle when Ali finished him off in the same round. It was a savage final beating, but nothing in comparison to Lyle's next two fights; fights that secured Lyle a special place in modern boxing history.

Shavers and Lyle hit each other with stunning power, with Lyle over in the second and Shavers over and out in the sixth. It was briefly the measuring stick for courage, suffering and brutality in a heavyweight fight; four months later Lyle and Foreman shifted the line forever when they met at Caesars Palace, Las Vegas.

After three rounds of raw power which sent both boxers reeling and rolling, the knockdowns came in the truly sensational fourth round. Foreman was dropped heavily but regained his feet quickly and then dropped Lyle. There was pandemonium at ringside – nobody there on the night was sitting – and with a knock-down each they both went for a finish. It was Lyle who connected with a right hand, and Foreman dropped face-first and disturbingly to the canvas. "When they go like that, they stay gone," said Foreman's trainer Gil Clancy.

However, this was the decade when the best fighters would be known as champions forever, and somehow Foreman regained his feet at the bell. It ended in the fifth after Lyle was caught with 30 unanswered punches before himself crashing face down. He tried, like Foreman had three minutes earlier, to get up, but at the count of nine only managed to roll softly on to his back for the count of 10. It was, as the commentator said, a fight of "total guts and power". Last year Lyle told me: "No two fighters have ever wanted to win like me and George."

On the first day of 1978 Lyle was again arrested on a murder charge when he was accused of shooting and killed a former prison pal a few hours earlier on New Year's Eve. He was acquitted of the killing the following December. "I did a lot for him," Lyle said of Rip Clark, the dead man. "He was in my home, I'm ghetto, and I'm a nigger too. I had 19 brothers and sisters. I've ached, I felt intimidated." When pushed Lyle refused to move or apologise.

His career never recovered from the lost year and he quit in 1980, but in 1995 made a mad comeback in search of a rematch with Foreman. It never happened and Lyle retreated to his beloved Denver to work with young fighters and children in danger. He died a folk hero after complications from a stomach abscess. "The problems were caused by the knife wounds from his prison injuries," Toft told me, which seems a fitting final twist to his life.

Steve Bunce

Ron Lyle, boxer and youth worker: born Dayton, Ohio 21 February 1941; married (marriage dissolved); died Denver, Colorado 26 November 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments