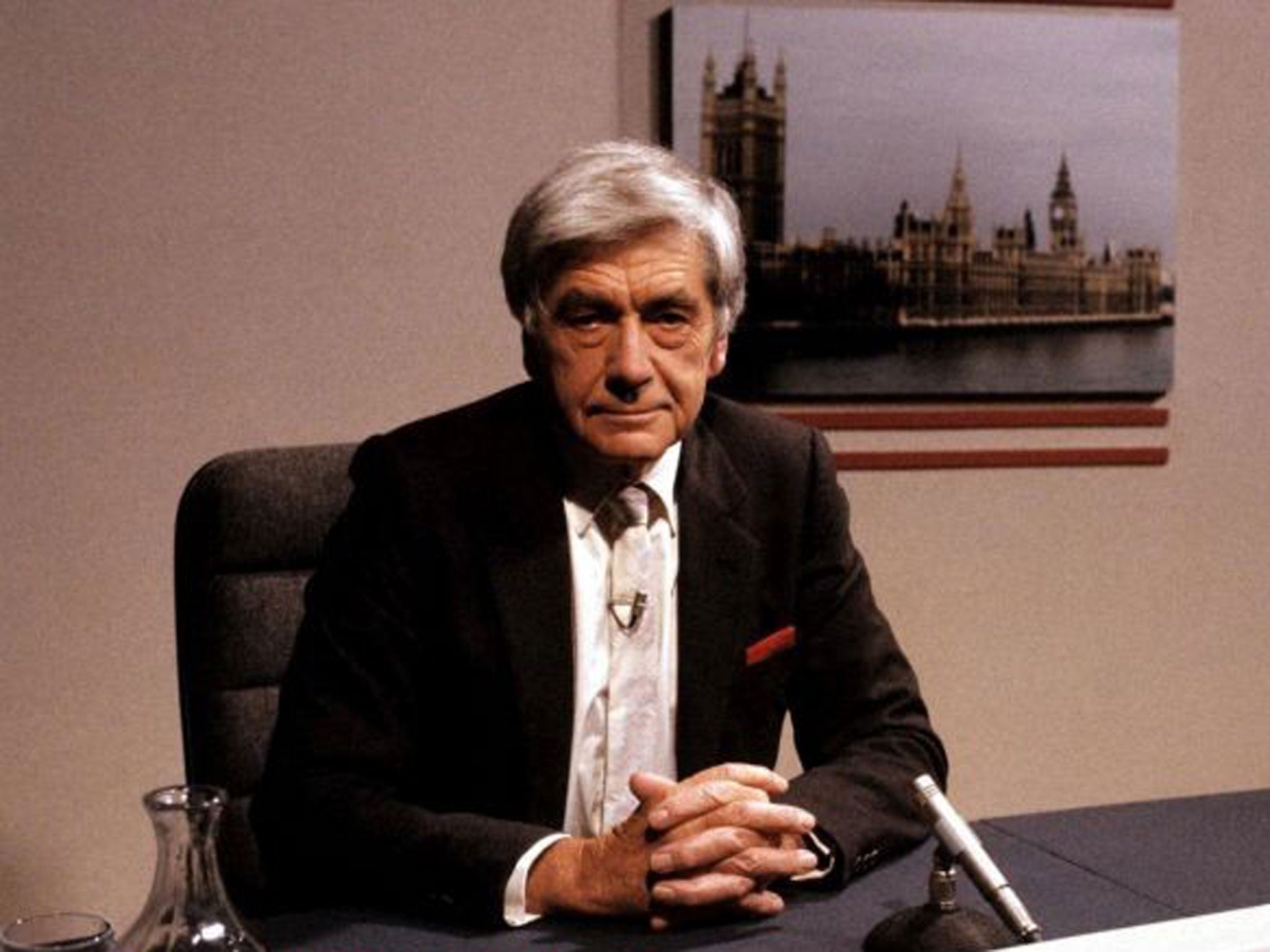

Robert Kee: Pioneering reporter whose career was distinguished by his strongly held principles

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Robert Kee was one of a small group of talented and conscientious television reporters who in the 1950s set standards and ground rules for the craft that still apply.

That his long career was marked by frequent switches of post, across all the main terrestrial channels, was in part a product of his stubborn refusal to depart from strongly held principles, leading to clashes with more pragmatic employers and colleagues.

Born in Calcutta in 1919, he attended Stowe School and Magdalen College, Oxford, where he graduated in modern history. Leaving Oxford in 1940, he became a pilot in the Royal Air Force. On a bombing mission in 1942 his plane was hit and he made a forced landing off the West Frisian Islands. Two of his crew were killed but he survived, only to be captured by the Germans and sent to a prison camp in Poland. From there he made an initially successful escape, but was rearrested near Cologne.

Soon after he returned to Britain he produced a novel, A Crowd is Not Company, based on his experiences at the prison camp. It was the first of four novels he wrote before switching in the 1960s to factual books, some derived from his television programmes.

In 1948 he joined Picture Post, a popular weekly magazine where several successful journalists cut their teeth – among them James Cameron, Fyfe Robertson and Sydney Jacobson, as well as the legendary photographer Bert Hardy. Kee was given freedom by the editor, Tom Hopkinson, to develop the measured and insightful reporting style he would later carry over into television.

One of his earliest articles was a perceptive examination of post-war race relations. “The British colour bar, one might say, is invisible,” he wrote in 1948, “but like Wells’ invisible man it is hard and real to the touch... It can only be solved by a true integration of white and coloured people in one society. And for that to take place there must be some sort of revolution inside every individual mind – coloured and white – where prejudices based on bitterness, ignorance or patronage have been established.”

He left Picture Post in 1951, soon after Hopkinson had been dismissed by the proprietor, Edward Hulton. For the next few years he contributed to the Observer, Sunday Times and Spectator until in 1958 he was persuaded to try his hand at television, becoming a reporter for Panorama, the BBC’s flagship weekly current affairs programme.

It was soon clear he had found his métier. In 1960 the critic Peter Black, in a tribute to the programme in the Daily Mail, wrote of “Robert Kee, the hot-eyed public prosecutor of the outfit, who specialises in political subjects with undertones of conscience, such as colour bar, flogging, the betrayal of old horses”. But in 1962 he and other Panorama stars, including James Mossman and Ludovic Kennedy, decided that the BBC was undervaluing and underpaying them. They left to set up Television Reporters International (TRI) with a view to making their own films and selling them to the BBC or ITV. After a few years the scheme proved unviable commercially and TRI was wound up.

Having burned his boats with the BBC, at least for the time being, Kee found work with the ITV network, in particular on the current affairs magazine This Week and a well-received series on Faces of Communism. Then in 1972 he was asked by ITN to present its first midday news bulletin, First Report, which later became News at One. It was a popular innovation and was one of the first news programmes to employ the technique, now commonplace, of having the newscaster directly interrogate reporters on location. In 1976 Kee’s work on it won him Bafta’s Richard Dimbleby Award.

Soon afterwards he drifted back to the BBC and in 1980 produced perhaps his most notable piece of work, a 13-part series called Ireland: a Television History. His producer was Jeremy Isaacs, who later wrote of how he marvelled at “Robert Kee’s unerring ability to marry the word to the image as he sat in the cutting room, writing”. He described watching Kee at work as “the best lesson I had in television”.

Early in 1982 he was invited to become the regular presenter of Panorama. “Merely by his presence, Robert Kee confers distinction on Panorama,” wrote Clive James in the Observer; but his presence was not to last long. In April of that year Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands and Margaret Thatcher sent a task force to repossess the territory. Such situations present broadcasters with a dilemma: should they follow their journalistic instincts and take a dispassionate view, giving equal weight to views for and against the action, or should they make allowances for the patriotic fervour invariably provoked by military operations overseas?

The 10 May edition of Panorama was devoted to examining public attitudes to the conflict. When Kee saw the first version he was uneasy, feeling that it gave too much exposure to opponents of the action. Although some changes were made before transmission, Kee thought – along with many politicians and commentators – that the balance was wrong, and that the prominence given to dissenting views could damage military morale.

He felt so strongly about it that he wrote a letter to The Times denouncing the programme and what he described as its “poor objective journalism”. After such a public airing of dissent it became clear that he could not remain as the face of Panorama, and he resigned a few days later.

He was not unemployed for long. He had been approached by David Frost and Peter Jay to become involved with a group of well-known television personalities applying for the franchise to run the first breakfast programme on ITV. Of the so-called Famous Five, Kee was the least famous – the others, along with Frost, were Michael Parkinson, Anna Ford and Angela Rippon – and his appearances on TV-am were, in the event, quite rare.

Despite a welter of advance publicity, TV-am failed to attract a large enough audience. Its rigorous approach to news – in contrast to the relaxed atmosphere of the BBC’s competing programme – seemed too demanding for the early morning. When its backers ejected Jay as chief executive and brought in Greg Dyke to take control of programming, the Famous Five broke up and Kee joined Channel 4’s Seven Days, where he stayed until 1988. After that he began work on his last major book, The Laurel and the Ivy: Parnell and Irish Nationalism, published in 1993.

Robert Kee, journalist and broadcaster: born Calcutta 5 October 1919; CBE 1998; married 1948 Janetta Woolley (divorced 1950; one daughter), 1960 Cynthia Judah (divorced 1989; one son, one daughter, and one son deceased), 1990 Catherine Trevelyan; died 11 January 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments