Robert Evans: Hollywood producer of legendary bravado who had a remarkable run of hits

In a golden age of cinema he brought the likes of ‘Rosemary’s Baby’ and ‘The Godfather’ to the screen

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Robert Evans was the Paramount Pictures executive who presided over a remarkable range of hits – notably The Godfather, Chinatown, Rosemary’s Baby and Love Story – and whose rakish and erratic personal style embodied the remarkable rise, fall and rise of a Hollywood player.

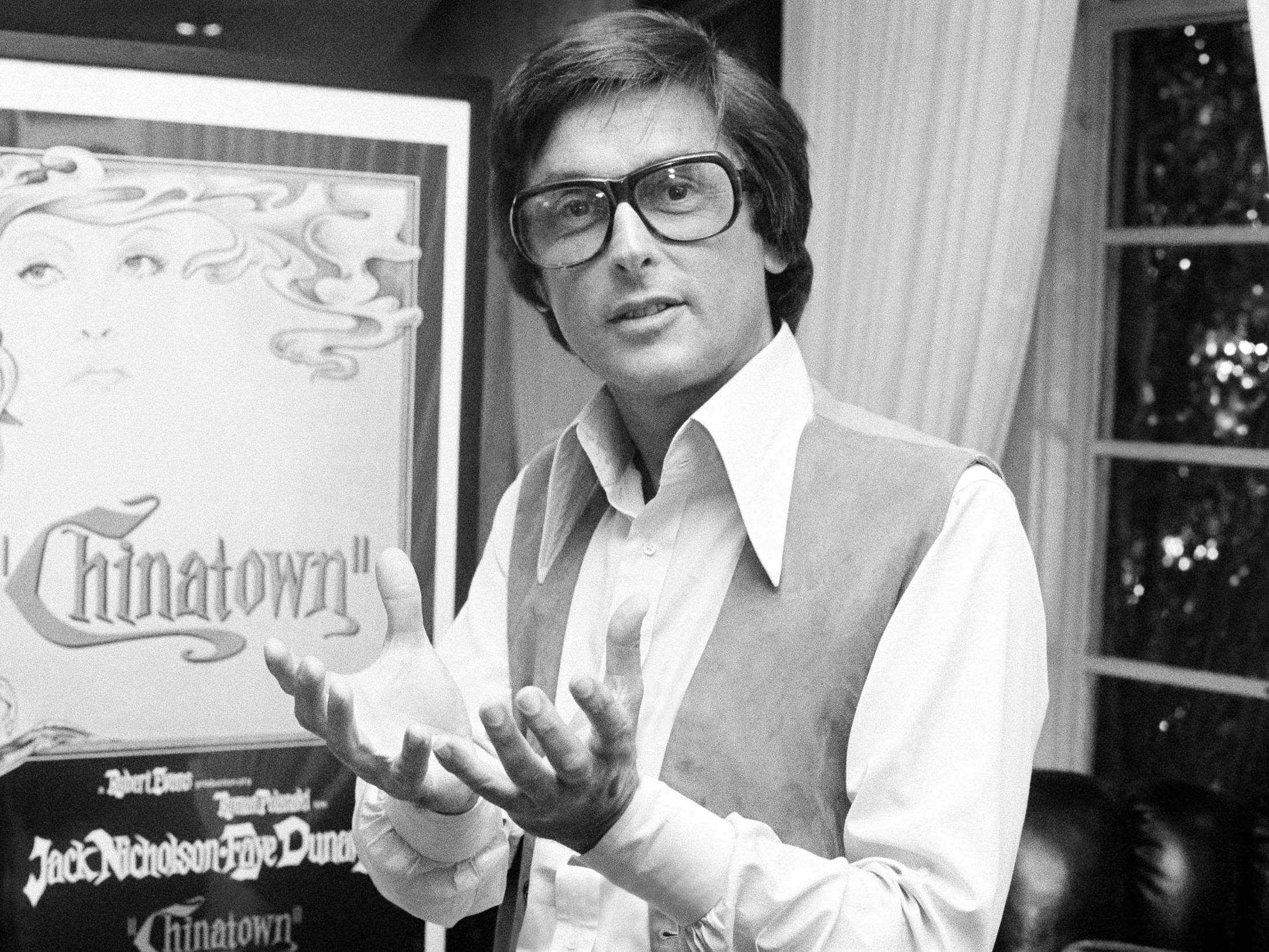

With his gravelly voice, large-framed designer glasses, perpetual tan and fondness for gold chains and suede jeans, Evans, who has died aged 89, brimmed with a rakish confidence and showmanship that propelled his career in the 1960s and 1970s. He was long considered one of the savviest production chiefs in Hollywood, but cocaine abuse gradually derailed his career.

As Paramount’s head of worldwide production from 1966 to 1975, his commercial choices and hunch for talent were credited with helping to lift the company’s sagging fortunes with a staggering variety of popular and often critical hits. They included The Odd Couple (1968), True Grit (1969), Serpico (1973), Paper Moon (1973), The Great Gatsby (1974), Death Wish (1974) and Coppola’s The Conversation (1974).

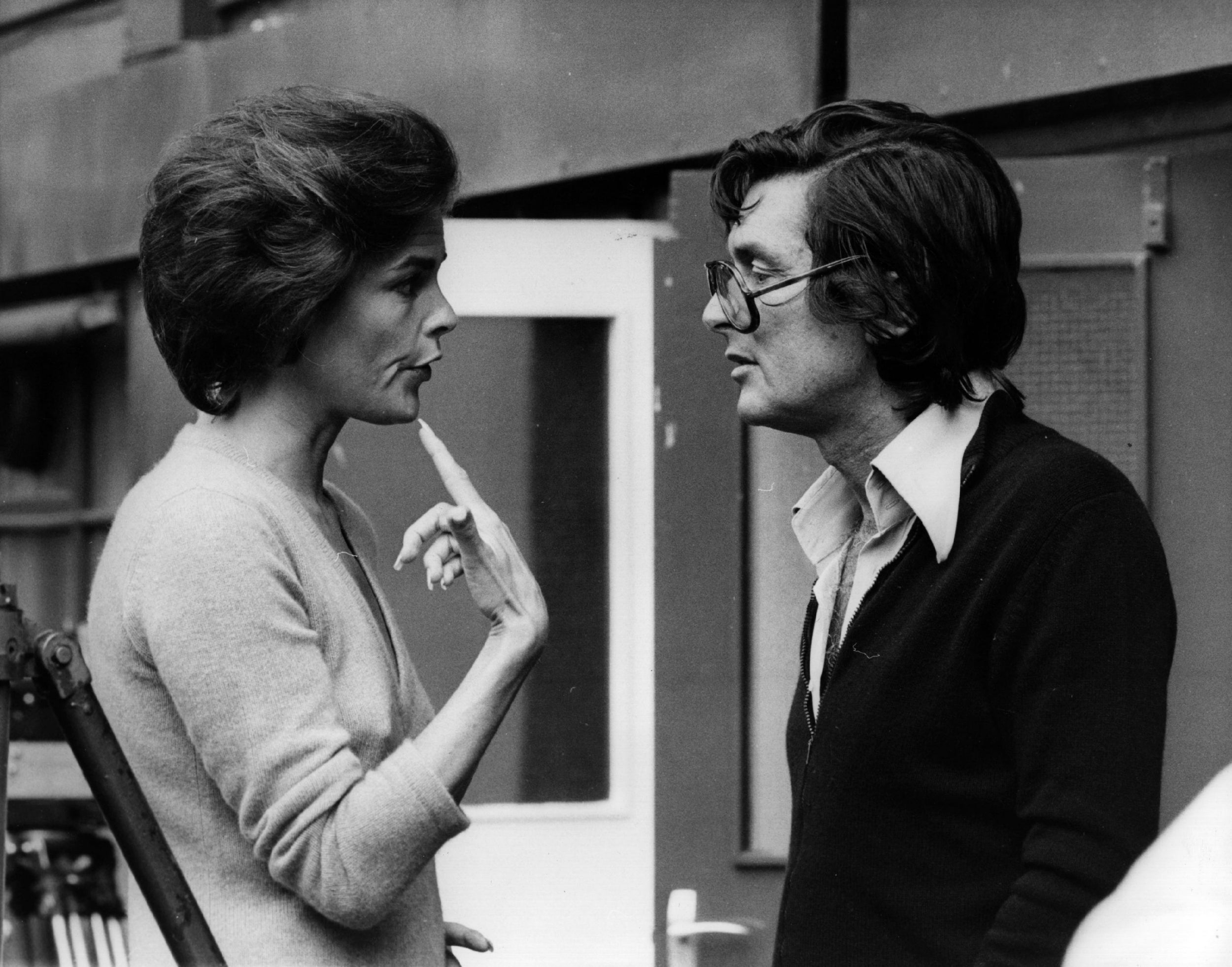

Evans championed directors other studios wouldn’t hire – and who worked cheaper. Roman Polanski was considered a young wild card from Europe when he was entrusted with the adaptation of Ira Levin’s Gothic novel Rosemary’s Baby. The 1968 film made a star of Mia Farrow.

He was married seven times to a succession of models and actors, including Love Story star Ali MacGraw and former Miss America Phyllis George. His fifth marriage, to Dynasty actor Catherine Oxenberg, was annulled after nine days in 1998.

Robert J Shapera – the J “standing for nothing I knew of”, he once wrote – was born in New York in 1930. He described his father as a frustrated pianist who went to dental school and ran his practice in Harlem. He was 10 when his father changed his children’s last name to Evans, in tribute to their dying paternal grandmother, whose maiden name was Evan.

By his twenties Evans had drifted into modelling menswear. He became a partner and salesman for the women’s clothing line Evan Picone, which had been co-founded by his brother Charles. In 1956 Evans was in Los Angeles on a sales trip when he was spotted beside the Beverly Hills Hotel’s pool by the actor Norma Shearer, who thought the young sunbather resembled her late husband, film producer Irving Thalberg. As it happened, MGM needed someone to play Thalberg in a biopic of silent movie actor Lon Chaney, Man of a Thousand Faces.

He got the part, but Evans’ acting career was brief and forgettable. During filming of the 1957 adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, nearly everyone involved rebelled at the casting of Evans as Mexican bullfighter Pedro Romero. But in a display of power that impressed Evans – and which he used for the title of his memoir – Twentieth Century Fox studio chief Darryl F Zanuck told the crew: “The kid stays in the picture.”

In 1966 Yvette Bluhdorn, the wife of industrialist Charles Bluhdorn, smoothed Evans’s path to run one of her husband’s smaller properties, Paramount Pictures, reportedly telling her husband: “We’ve got to get a good-looking guy, real sexy, to run the studio.” Thus Evans catapulted into one of the most powerful jobs in Hollywood.

He had a huge success in 1970 with Love Story, a sappy melodrama that broke box-office records, and followed this up with The Godfather. Years earlier, for a pittance, he had optioned an unfinished mafia potboiler by an obscure author named Mario Puzo. Mob movies were not considered big draws, but when Puzo’s novel became a bestseller, The Godfather was poised to become Paramount’s next big hit. Of his working relationship with director Francis Ford Coppola, he said: “Francis and I had a perfect record: we didn’t agree on anything, from editing to music to sound.”

The Godfather (1972) and its sequel, The Godfather: Part II (1974), were commercial and artistic triumphs but he grew restive as a mere employee of the studio: he wanted to own a stake in his films. He got his chance by producing the 1974 LA noir Chinatown, working with pals Jack Nicholson and Roman Polanski. But after Chinatown, Bluhdorn brought in Barry Diller to be the studio’s new production chief. Evans remained on the lot, producing films ranging from lauded thriller Marathon Man (1976) to duds such as Popeye (1980).

In 1980 Evans pleaded guilty to cocaine possession and was sentenced to one year’s probation. Worse trouble came his way when he met a 33-year-old road show promoter named Roy Radin, who became an investor in the film The Cotton Club. Directed by Coppola and set at a Harlem jazz club in the 1930s, the film was widely panned. By that time, Radin had been found dead in a dry creek bed off a highway northwest of Los Angeles. He had been shot 13 times.

Ultimately, four people were convicted over Radin’s death, including a former drug dealer and girlfriend of Evans who had introduced Radin to the producer. The notion that Evans was orbiting an underbelly of drugs and murders-for-hire made him persona non grata for years.

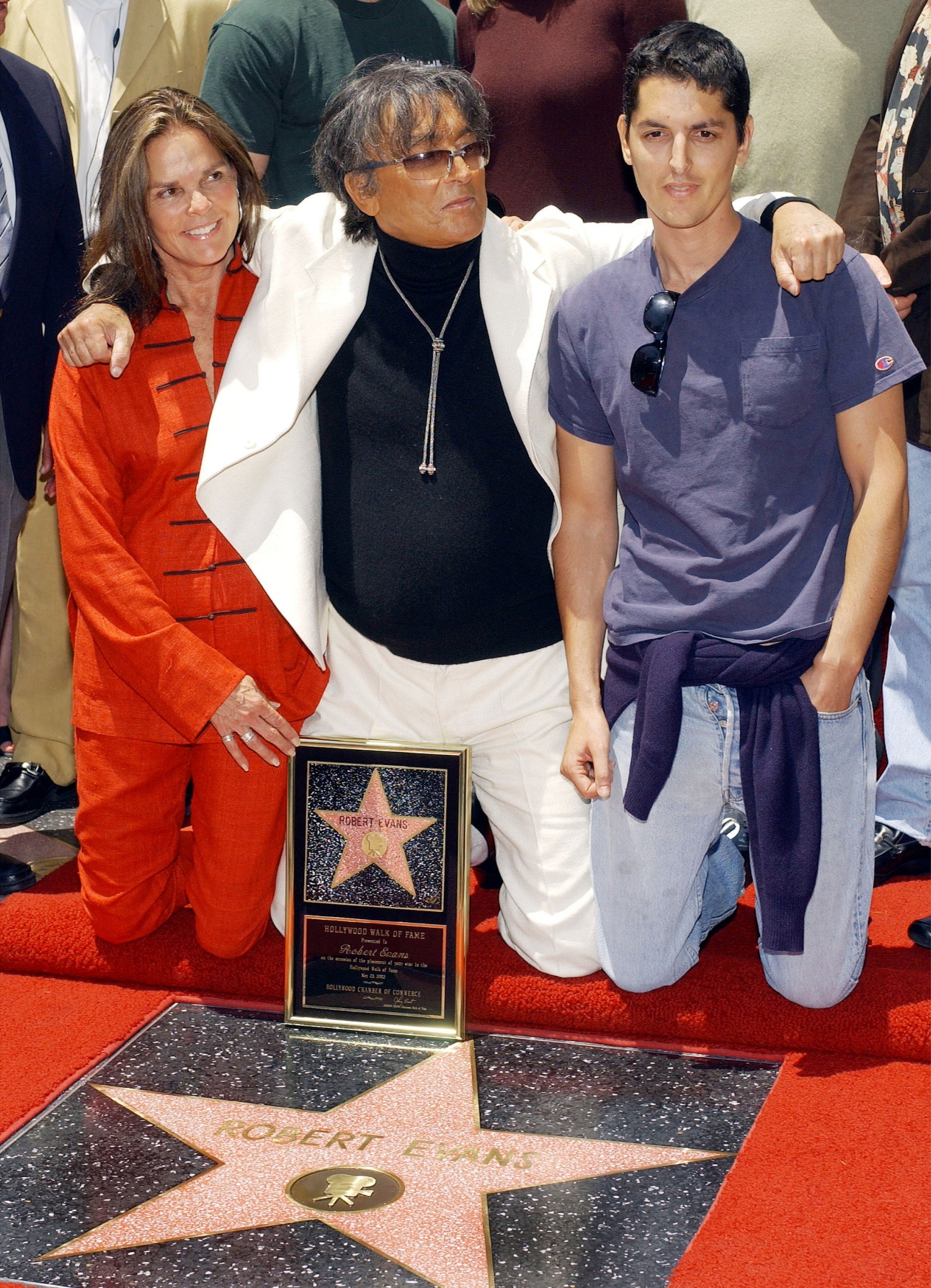

He returned to industry favour with his 1994 memoir, The Kid Stays in the Picture. Returning to Paramount, he produced movies on a more modest scale – including Sliver (1993) and How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days (2003) – but remained full of the bravado that defined his heyday.

He is survived by his son Josh, from his marriage to MacGraw.

Robert Evans, film producer, born 29 June 1930, died 26 October 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments