Robert Byrd: Politician who began his career as a member of the Ku Klux Klan but came to embrace civil rights

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

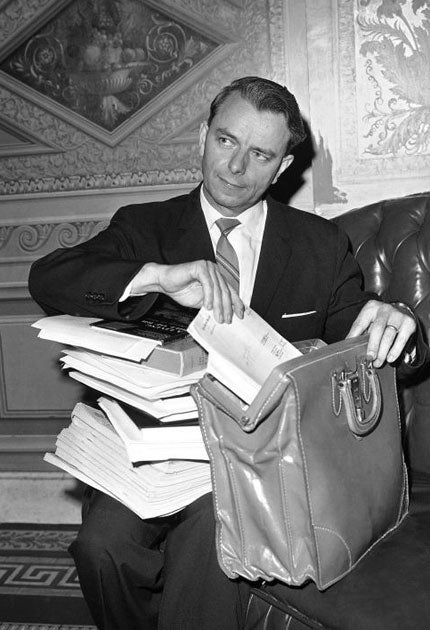

Your support makes all the difference.Robert Byrd's middle name was Carlyle – but to watch him during a career in the Senate that shattered every record, the C might have stood for Cato, Cassius or Cicero.

With his silvery mane of hair, a bearing that demanded a toga rather than the dark suit in whose pocket he unfailingly carried a copy of the US constitution, and the speeches sprinkled with classical quotations, you might have imagined he was an eye witness to the murder of Julius Caesar. Byrd did not merely acquire a vast institutional memory for the place in which he served for more than half a century and loved above all other. By the end, he almost was the place.

In November 2006 he was re-elected to an unprecedented ninth six-year term as Democratic Senator for West Virginia. A few months earlier, he had broken Strom Thurmond's record as the longest-serving Senator. By January 2007, Byrd was the last Senator from the 1950s still alive. In early 2008, there were eight of his colleagues not even born when he first took his seat in January 1959.

Over the years he held every senior position the body: majority leader (twice), minority leader, and majority whip. For three spells, as oldest member of the majority party, he was the Senate's president pro tempore, putting him third in line of succession for the White House, behind the vice-President and the Speaker of the House.

To be sure, Byrd was not to everyone's taste. He could be insufferably pompous and long-winded. His obsession with procedure and Senate rules was often infuriating. Undeniably, however, and even by the remarkable standards of America, he was a self-made man as few others.

The legislator who quoted Cicero and Demosthenes was born Cornelius Calvin Sale, Jnr, in the mountains of North Carolina. When he was a year old his mother died in the 1918 flu pandemic and his father sent the children to live with relatives. The young Cornelius was raised by Vlurma and Titus Byrd, an aunt and an uncle who lived in the coal-mining area of southern West Virginia.

The renamed Robert Byrd was a bright student, who finished top of his class at high school. But his adopted family, poor at the best of times, had no money to send their son to college in the depths of the Great Depression. Instead he worked as a petrol station assistant, butcher and welder, finding the time to obtain degrees as an outside student at three West Virginia colleges. (Only in 1963 –and long since installed as a US Senator – did he complete his post-graduate education by earning a law degree from American University in Washington DC, after seven years of part-time study). And like many a poor young boy with southern roots at that time, he joined the Ku Klux Klan.

Byrd was a Klan member for less than 12 months, between 1942 and mid-1943. But he kept up contacts for much longer, as proved by his own admission that it was a senior Klan official, the Grand Dragon Joel Baskin, who was then responsible for West Virginia, who encouraged him to enter politics.

In 1946 Byrd was elected to the state legislature – in part thanks to his charming voters with his virtuosity on the hillbilly fiddle. Six years later he went to Washington. His three terms as a Congressman were undistinguished, but in 1958 he defeated an incumbent Republican to win a seat in the US Senate. For Byrd, it was a second marriage. Entering the Senate, he once said, "was like falling in love with my childhood sweetheart. I couldn't live without her." Later he would prove his devotion by writing a definitive four-volume history of the institution.

At the start, Byrd was just another southern Democrat, conservative and white supremacist. He tried to filibuster Lyndon Johnson's ground-breaking 1964 civil rights bill and voted against confirmation of Thurgood Marshall as the first black justice on the US Supreme Court. No friend of John Kennedy, he campaigned unsuccessfully for Hubert Humphrey in the pivotal 1960 West Virginia Democratic presidential primary.

But by the 1970s he was shifting leftwards. Byrd still stood on his dignity (it was always Robert, not "Bobby" or, heaven forbid, "Bob"). But he came to embrace civil rights and desegregation. Most important of all he acquired an unrivalled mastery of Senate procedure, making himself indispensable to the party leadership. By 1971 he was majority whip and six years he later took over from Mike Mansfield as Senate majority leader.

Thereafter, even when Republicans controlled the chamber, Byrd was among the most influential senators. As either chairman or ranking Democrat on the Appropriations Committee for two decades, he had as big a say as anyone on Capitol Hill on how Government money was spent. In the process he became a supreme exponent of pork-barrel politics, channelling hundreds of millions of federal dollars to his impoverished state. By 2008 almost 40 buildings and infrastructure projects in West Virginia bore his name. And that was while Byrd was alive.

But the biggest paradox still lay ahead. This Senator and former Klansman who, had he represented a state of the old Confederacy would almost certainly have become Republican, became a hero to the liberal left. The reason was his ferocious opposition to the Iraq war, and his contemptuous criticism of President Bush – and also of his beloved Senate which, he believed, had cravenly surrendered its rightful say over war and peace to an overweening executive branch.

"Today I weep for my country," he said on 19 March 2003, as the invasion began. "The image of America has changed. Around the globe, our friends mistrust us, our word is disputed, our intentions are questioned. Instead of reasoning with those with whom we disagree, we demand obedience or threaten recrimination." Of all his 18,000-odd Senate votes, his vote against authorising the war in October 2002 was the one of which Byrd was most proud.

Another national security battle showed the quixotic quality of the man. In 2002, he fought the Bush administration's plan to set up a Department of Homeland Security because he believed not enough time had been allocated for debate. Why, he was asked, did he waste so much time on a clearly lost cause?

"That question misses the point," Byrd replied. "The matter will be there for a thousand years in the record. I stood for the Constitution, I stood for the institution." Even if his voice was ignored at the time, "there will be a future member who will come through and comb through these tomes." Criticise him as you will. If nothing else, Robert Byrd had a sense of history.

Robert Carlyle Byrd, politician: born North Wilkesboro, North Carolina 20 November 1917; Member, US House of Representatives, West Virginia 6th District 1953-1959; elected US Senator, West Virginia 1958, 1964, 1970, 1976, 1982, 1988, 1994, 2000, 2006; Senate majority leader 1977-1981, 1987-1989, minority leader 1981-1987; married 1937 Emma Ora Jones (died 2006; two daughters); died Washington DC 28 June 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments