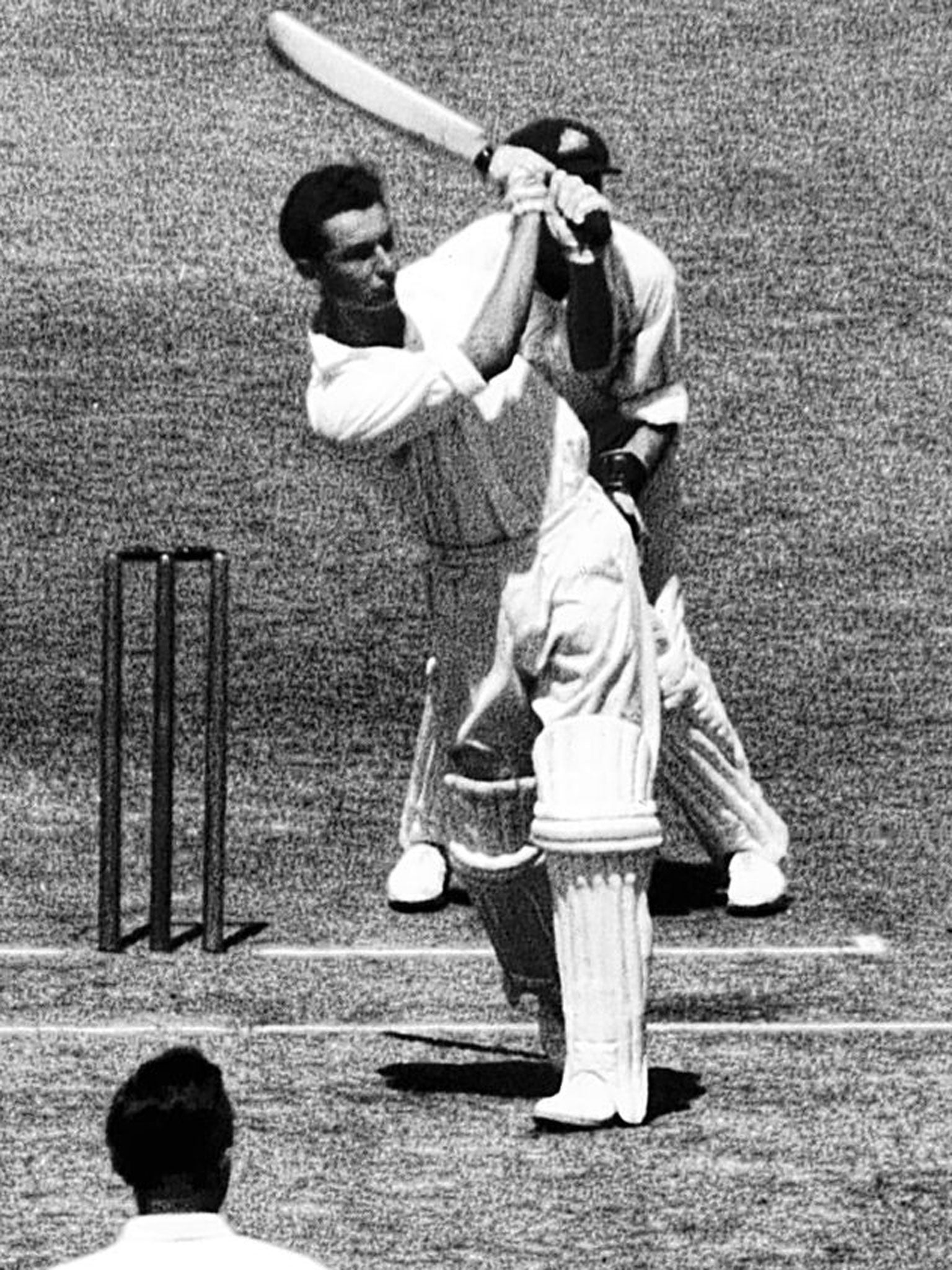

Reg Simpson: Batsman for England and Nottinghamshire whose swashbuckling style helped brighten the postwar years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the postwar years of austerity there were few more attractive sights in English cricket than the Nottinghamshire batsman Reg Simpson. With a quick eye and the natural gift of timing he developed a back-foot technique that seemed to give him more time than anyone else against the fast bowlers. If they bowled bouncers he swayed effortlessly out of the way. If they pitched it up he drove them elegantly. Always he played with a positive spirit, prepared to embrace risk in pursuit of victory.

A grocer's son from Sherwood Rise, north of Nottingham, he fell in love with cricket at primary school, visiting Trent Bridge, where for him there was no more thrilling a sight than the hawk-eyed Indian prince Duleepsinhji of Sussex playing with graceful artistry the lightning-fast bowling of Harold Larwood. In the back garden at home it was Duleep he wanted to be.

At Nottingham High School he broke the record in the 100-yard sprint, scored dashing tries at rugby and attracted the county cricket club's attention. He joined the Nottingham Police, becoming a cadet detective in the Special Branch. Then when he was 19 war broke out, blocking his path into first-class cricket. At first he remained a policeman, scoring big runs in wartime matches at Trent Bridge; then he joined the RAF, learning to fly in Arizona and finishing up in India. "Don't fly too high," his mother beseeched him, but it was not advice Simpson was ever going to take. At the controls of a plane or car, or with a bat in his hand, he was not temperamentally inclined to caution.

In India he flew more than 1,000 hours, but he found time for cricket, making his first-class debut for Sind against Bombay at Karachi. Late in his life, to his great amusement, Wisden took to listing him as RT Simpson (Sind & Notts). He got back to England in the middle of 1946, and within a month of his county debut scored 201 against Warwickshire.

He was determined to play his cricket as an amateur, and this became possible when the bat-makers Gunn & Moore took him on. It was only a pretence of amateurism, but Simpson, unlike some with such jobs, took his work seriously, becoming in time managing director. He was offered the captaincy of Northamptonshire but he stayed at Trent Bridge, where he skippered the side from 1951 to 1960.

He toured South Africa in 1948-49, where he sorted out his weakness against spin bowling. Gloucestershire's Jack Crapp told him how the great Wally Hammond had concentrated on the ball in the air, not the hand delivering it. "The funny thing was," Simpson said, "when you did that, you actually saw the different action of the hand more clearly." The following summer, against Leicestershire, with their deadly chinaman bowler, the Australian Jack Walsh, he hit two hundreds in a match, the second in a sensational run chase in which Notts scored 279 runs in 35 overs. That summer, against New Zealand at Old Trafford, he hit his maiden Test century.

Simpson played 27 times for England, scoring four centuries, the most memorable of which was at Melbourne in the last Test of the 1950-51 series. England had lost the first four games, making their postwar record against Australia played 14, drawn 3, lost 11. But Simpson finally raised the nation's spirits with a match-winning hundred in the first innings. He stood up to the pace of Lindwall and Miller, mastered the mystery spinner Iverson, and in a crucial last-wicket partnership of 74 with Roy Tattersall, when he took his score from 92 to 156, he manipulated the strike so that he could face six out of eight balls each over. "The situation really suited me. I could take some calculated risks and play my shots."

The former Australian Test cricketer Jack Fingleton wrote that "He could be one of our great modern players," and Simpson underlined the verdict with a dazzling 137 in the first Test of the summer against the South Africans. Yet even in that innings the warning signs were there in the reaction of the more conservative Len Hutton, soon to become England captain. "I hit Athol Rowan over the top to the pavilion for a near-six and, as we crossed, he said to me, 'This is a Test match, you know.'"

By the fourth Test Simpson was out of the side. "All the time I was playing Test cricket, I had the feeling I was fighting for my place, and it does make you over-cautious. If somebody had said to me, 'You're in for five matches,' I could have attacked in my own way as I did at Notts."

He never became a fixture in the England side, but he continued to entertain the crowds at Trent Bridge. As late as 1962, when he was 42 years old and only playing part-time, he topped the national batting averages. In all first-class cricket he hit 64 centuries, 10 of them doubles.

For many years he was the driving force at Nottinghamshire, and was chairman of the club as they rose from the lower depths to win the championship in 1981. Though he disapproved of much in the modern game he remained a great believer in playing positively. Still playing at the age of 63, he was proud of his Man of the Match award in a Lord's Taverners game in which he hit a 50 off a bowling attack that included Paul Allott and Richard Hutton. At the time of his death he was England's oldest Test cricketer.

Reginald Thomas Simpson, cricketer: born Sherwood Rise, Nottingham 27 February 1920; played for Nottinghamshire 1946-63, 27 Tests for England 1949-55; married three times (two children); died 22 November 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments