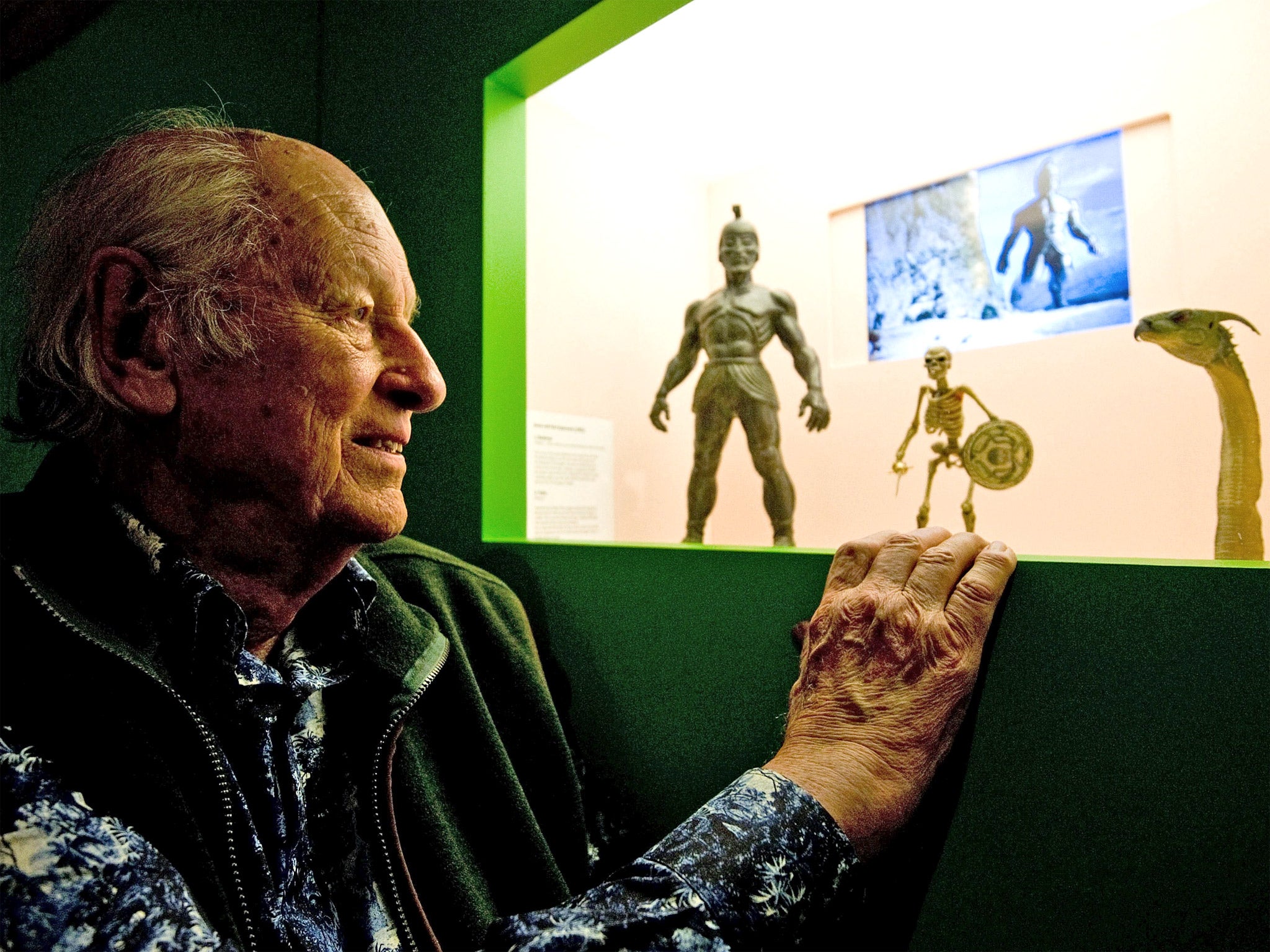

Ray Harryhausen: Pioneer of special effects hailed as the master of stop-motion animation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Before the rise of digital technology and computer animation, the best way to create on film the illusion of monsters walking the earth was by the painstaking method of stop-motion animation – small models moved frame by frame in front of the camera. Ray Harryhausen was the undisputed master of this art form, and was the first superstar to emerge from the field of special effects.

His movies bristled with images that left a lasting impression on cinemagoers: remember the sword-fighting skeleton army from Jason and the Argonauts (1963) and the pterodactyl that flew off with Raquel Welch in One Million Years BC (1967)? They inspired a generation of artists and animators to tread similar paths, and films such as Star Wars (1977) and Jurassic Park (1993) are testament to the influence Harryhausen wrought over cinema.

The power of cinema first inspired Harryhausen when he was 13 years of age and his mother took him to see King Kong (1933) at Grauman's Chinese Theater in his native Los Angeles. It was a trip that changed his life. "I came out of the theatre stunned and haunted. I wanted to know how it was done," he said. Over the next decade he watched King Kong no fewer than 80 times.

Harryhausen began researching and learning the rudiments of stop-motion animation (his early film experiments were carried out in a makeshift studio housed in the family garage), discovering he had a natural talent for it, as well as for creating clay sculptures and models, mostly of dinosaurs, one of his fascinations ever since his parents took him regularly as a boy to see the dinosaurs at the LA County Museum of Natural History.

He managed to arrange a meeting with his hero, the King Kong effects pioneer Willis O'Brien, and took along with him a suitcase full of his dinosaur models. O'Brien was encouraging, if critical, suggesting the young student might wish to study anatomy in order to bring more accuracy and character to his creations.

In 1939 Harryhausen enrolled in art classes and perfected his talents for drawing and sculpture. He also dabbled in drama, a personal challenge for a rather introverted youth. He was later to exploit what he learnt in his professional life, and believed he always produced his best animation by a feel for the acting rather than through a quest for technical perfection.

In many ways Harryhausen was an auteur. Not only did he create the models himself but he often worked unassisted for months to perfect a single film sequence. It was a labour of enormous dedication – some might say an obsession. But his hands-on approach gave a life and personality to his space monsters, dinosaurs and mythical beasts which today's computer animation would struggle to match.

Harryhausen continued to experiment and improve his animating film technique, ably supported by his parents. His father, a former machinist, helped build the more intricate jointed models needed, while his mother designed and sewed miniature costumes. His home-made footage won him a job in 1940 with the acclaimed Hungarian animator George Pal, then beginning his series of "Puppetoons". Harryhausen spent two fulfilling years getting practical experience in modelling techniques and photography.

In 1942 he was drafted into the US army, putting his skills to good use making training films. After the war Willis O'Brien remembered the young fan desperate to get into the film business and hired Harryhausen as his assistant on Mighty Joe Young, a giant gorilla film in the same vein as King Kong. It was the break Harryhausen had been waiting for. Mighty Joe Young took almost three years to prepare and shoot. Finally released in 1949, it won an Oscar for its visual effects.

The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953) presented Harryhausen with his first opportunity as a special effects supervisor. The story of a dinosaur frozen in Arctic ice reawakened by a nuclear explosion which then makes its way to the US and goes on the rampage through New York, the film was a surprise hit. It began one of the most popular movie cycles of the decade, of films about monsters created out of nuclear testing, from giant mutant ants in Them (1954) to a 400ft Tyrannosaurus Rex in Godzilla (1956).

Out of this cycle emerged a film partnership that was to shape Harryhausen's future. The producer Charles H Schneer hired him to handle the intricate effects in It Came From Beneath the Sea (1955), a story about a giant octopus unleashed by an atomic blast and terrorising San Francisco. It was the first of 12 pictures they would make together, many of them revolving around the themes of Greek and Arab mythology.

For years Harryhausen had wanted to make a film about Sinbad, the legendary Arab sailor. Schneer and Harryhausen's groundbreaking The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad (1958) found worldwide success and heralded the film process called "Dynamation", Harryhausen's own method of combining stop-motion effects seamlessly into live-action backgrounds.

The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad was the making of the Harryhausen legend, featuring such eye-popping marvels as a Cyclops, a snake woman and a colossal dragon. It set the pattern for most of the Schneer-Harryhausen films to follow, not least two subsequent Sinbad sequels – The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1974) and Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977).

By then he had made London his permanent base, setting up his own studio in Slough. He was married in 1962, to the Scottish horsewoman Diana Bruce; he claimed he had not had time to marry earlier because he was too busy with his career.

With Schneer he branched out into other film territories, adapting two classic fantasy novels for the screen, HG Wells's Mysterious Island (1961) and Jules Verne's First Men in the Moon (1964), as well as the cowboys-meet-dinosaur epic Valley of Gwangi (1968). Clash of the Titans (1981) turned out to be his swansong. Disappointed by the harsh critical response to it, he announced his retirement at the comparatively early age of 61.

He continued to enjoy the odd guest spot as an actor, in films such as Spies Like Us (1985), Beverly Hills Cop 3 (1994) and the 1998 remake of Mighty Joe Young, as well as making personal appearances at science fiction conventions. Although he was always amiable with his devoted fans, Harryhausen was shy and secretive about his profession and his private life. "When a magician ceases to be a mystery his fans will soon begin to lose interest in him," was his response when pressed about how he had achieved certain effects in his films.

In 1992 Harryhausen was belatedly recognised by his peers when he won an Oscar for lifetime achievement. There to present him with it was the writer Ray Bradbury, who was an old schoolfriend; as children they had made a pact never to grow up, to always fantasise about dinosaurs and space travel. And despite his enormous success and his place in film history, Harryhausen scarcely seemed to have changed from the serious, unflappable youth who had first moved into the business. To many of his friends he remained a child at heart who spent his time playing with toys and living out his dreams.

Robert Sellers

Ray Harryhausen, special effects technician and stop-motion animator: born Los Angeles 29 June 1920; married 1962 Diana Bruce (one daughter); died London 7 May 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments