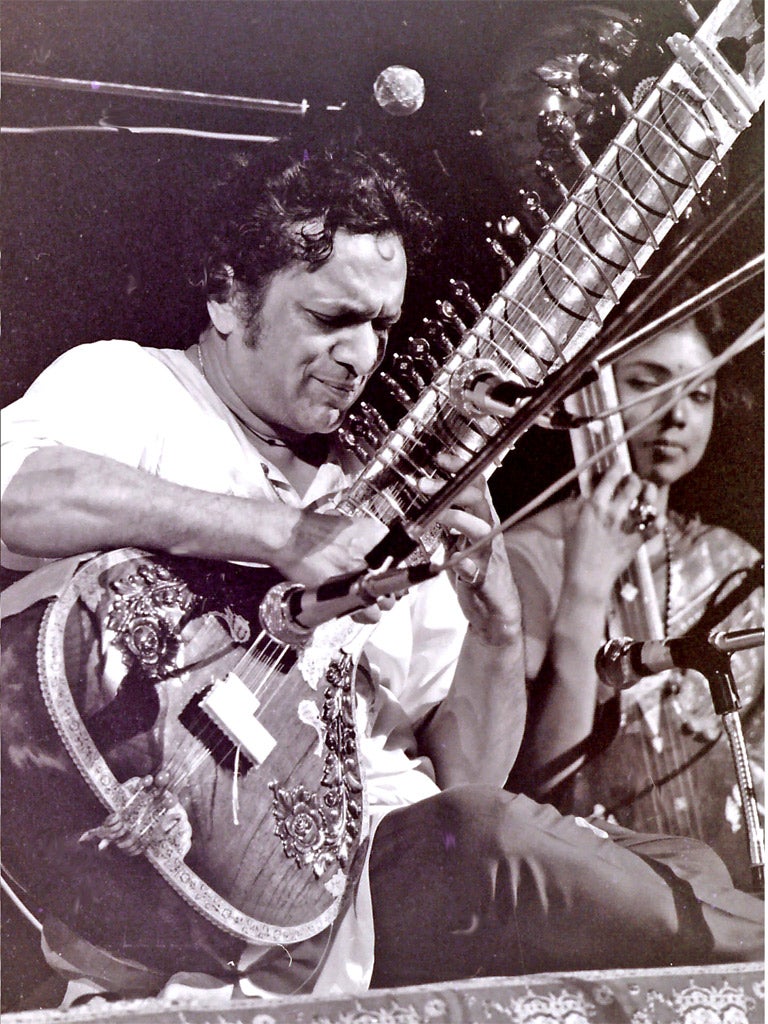

Ravi Shankar: Sitar virtuoso and composer whose work introduced Indian music to Western audiences

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ravi Shankar will be remembered in two strikingly different ways. First and foremost, he was probably the greatest sitar-player of post-Independence India. Secondly, he was principally responsible for introducing classical Indian music to western audiences and musicians, including the violinist Yehudi Menuhin and George Harrison of the Beatles, whose association with Shankar from 1966 made him briefly (and somewhat reluctantly) the first Indian pop star and an "honorary hippie".

He also had a considerable career as a composer for ballets, such as The Discovery of India (based on Jawaharlal Nehru's book), and film, notably Satyajit Ray's Apu Trilogy (1955-59) and Richard Attenborough's Gandhi (1983); and he collaborated extensively with the composer Philip Glass.

His family hailed from Bengal, perhaps the most artistically gifted region of India, but his father, an orthodox and scholarly Brahmin, had been a minister in the service of a maharaja outside Bengal and had settled in Varanasi (Benares), where Ravi was born in 1920. The atmosphere of the holy city made a tremendous impression on his mind as a child.

Besides the singing in temples and during festivals, the palatial houses lining the Ganges each kept its own player of the shenai, an oboe-like instrument whose piercing music would haunt the ghats along the river in the early morning and evening. Shankar made full use of his childhood experience in scoring the magical Benares scenes in the second film of the Apu Trilogy; in 1978 he founded a research institute for music and the performing arts in Varanasi.

He was the youngest of four brothers who survived to adulthood. Uday, the eldest and a celebrated pioneer of Indian dance in the West during the 1920s and '30s, was, Shankar often said, "my first hero." He took the 10-year-old Ravi into his troupe and showed him Paris, Monte Carlo and Hollywood, making him "a part of the international artists' fraternity." He also gave him an insight crucial for his own world tours as a musician from the mid-1950s.

"I learnt from Uday not only the art of presentation but also the proportion of presentation – the exact proportion that is needed to make Indian music acceptable to the West." (His own performances in India lasted four hours at a minimum; in the West, he would observe with a smile, "They were always trying to lock up the hall while I was still playing.")

Uday introduced his brother, aged 13, to his second hero, the renaissance figure Rabindranath Tagore, who touched Ravi's head and said, "Be great like your father and your brother," making shivers run through his body. Unlike many Indian classical musicians, purist in attitude, Shankar developed a taste for Tagore's more than 2,000 songs, which drew freely on a great diversity of styles, Indian and western, without respecting traditional musical boundaries. In Bengal today they appeal at all levels of musical appreciation, from connoisseur to rickshaw wallah, and in the rest of India they have been poached for some of the most popular Hindi film songs. "Tagore had the genius of composing 10 different tunes from whatever he heard," Shankar said in 1991. "I don't think his creativity ever knew any bounds."

Three years later, in 1936, at Dartington, the college of arts in Devon inspired by Tagore, Shankar met his next and perhaps most formative influence. He had gone there to dance, and at the same time had taken lessons in sitar from the greatest musician of modern India, Ustad Allauddin Khan, who was accompanying the troupe. To Shankar, who had by now lost his parents, Allauddin would always be known simply as Baba (Father).

Two years after that, he decided to join his guru in a small village in central India to begin seven years of austere, intensive training rooted in the Hindu (and Gandhian) ideal of brahmacharya. Nothing – not fine clothes, nor fancy foods, nor love affairs and sex, in fact nothing of any kind that encouraged physical desire – was permitted. Shankar had to sleep on a cot made of four pieces of bamboo tied together with coconut rope. For his fellow pupils, the son and daughter of Allauddin – Ali Akbar Khan (modern India's greatest sarod player) and Annapurna – conditions were even more severe. (In 1941, Shankar and Annapurna had an arranged marriage, although they later separated; they had a son, Shubho, who died in 1992.)

The contrast with Shankar's life in the dance troupe was wrenching. As he remarked feelingly in his 1968 autobiography, My Music, My Life, "There are so many things one could add about Ustad Allauddin Khan. He belongs to a school that seems so far removed from our modern industrial era, and yet, in every way, he has been ahead of his time, injecting a new significance and life into Indian instrumental music. With him will pass an era that upheld the dedicated, spiritual outlook handed down by the great munis and rishis who considered the sound of music, and, to be Nada Brahma – a way to reach God."

The book appeared in 1968, four years before Allauddin's death, aged 110, just as Shankar was reaching the pinnacle of his fame in the West. After eight years as instrumental music director at All-India Radio he had given his first foreign concert in 1956. His breakthrough came in 1963 with three greatly admired recitals at the Edinburgh Festival.

In 1966 he gave lessons in India to George Harrison, who had already played sitar on "Norwegian Wood" on the Rubber Soul album, used an uncredited player on Revolver's "Love You To" and played himself again on Sergeant Pepper's "Within You Without You". In 1967, in New York, at a concert for UN Human Rights Day, Shankar played a duet with Yehudi Menuhin. Then, in 1969, at the Woodstock Festival, and in 1971, at two fund-raising concerts in aid of Bangladesh, Shankar appeared with Harrison. The same year he recorded perhaps his best-known East-West composition, a concerto for sitar and orchestra, playing with the London Symphony Orchestra.

Inevitably, there were mixed feelings on all sides, including Shankar's; he once described the 1960s fad for Indian music wryly as "Capital E music: Exotic, Exciting, Esoteric, Ethnic." None of Shankar's compositions beyond the bounds of Indian music – where he is credited with the creation of numerous ragas – has been received with lasting acclaim. Most are unlikely to survive as other than curiosities. Probably Shankar was too steeped in his own music to draw upon western music creatively, unlike Tagore or Satyajit Ray. In India, by contrast, for many years there was fierce criticism of him for "selling out" to the West, though this had largely died down by the time he published his fascinating second autobiography, Raga Mala, in 1997.

No doubt sour grapes were being squeezed, and Shankar admitted to being an angel and a devil at the same time. He was by no means the first great Indian artist to feel ambivalent about his countrymen. "At times I feel I don't belong to today," he said. "My roots are so deep in the past that sometimes I feel myself a stranger, even in my own country."

Part of Shankar's musical legacy lies in his two daughters. In the 1970s he had had an affair with a New York concert promoter, Sue Jones. She gave birth in 1979 to Norah, who became a musician and in 2002 released her debut album Come Away With Me, a fusion of jazz, pop and country, to great acclaim. She has gone on to win nine Grammy Awards, on one occasion sharing the limelight with her half-sister Anoushka, who in 2003 became the first woman to be nominated in the World Music category.

Anoushka was born two years after Norah; her father had been in a relationship with Sukanya Rajan (they eventually married in 1989). Born in London, Anoushka was raised in Encinitas, California, to where Shankar and Sukanya had moved. She learned the sitar with her father as a child, making her concert debut in Delhi at the age of 14 and going on to tour with her father.

In 2007 the half-sisters played together on Anoushka's album Breathing Under Water, a fusion of Indian music and western electronic pop; she also performed a duet with her father on the album, and has given several performances of Ravi's sitar concertos, the third of which was written for her. She also wrote a book about her father, Bapi: Love of My Life, in 2002; that year she played a composition by her father at the Concert For George, in memory of Harrison, who had died the previous year.

Shankar had suffered heart and respiratory problems for several years and recently went into hospital in La Jolla, California, undergoing heart-valve replacement surgery. He gave his last concert, with Anoushka, in Long Beach, California, in early November. Although he was in a wheelchair and with an oxygen supply, once he began to play his sitar, his old vitality and enchantment returned.

Andrew Robinson

In 1965 some British beat group musicians started experimenting with Indian sounds including the Yardbirds ("Heart Full Of Soul"), the Kinks ("See My Friend") and the Beatles ("Norwegian Wood"), writes Spencer Leigh. The following year there was the Byrds ("Eight Miles High") and the Rolling Stones ("Paint It Black") as well George Harrison playing sitar on the Beatles' Revolver.

When Harrison met Shankar in 1965, he asked for instruction. Shankar showed him how to hold the instrument and how to sit but said it took several years to become competent. On the Beatles' frenetic, final US tour of 1966, Harrison sequestered himself away to listen to Shankar's instruction tapes and to practise. He studied with Shankar in Bombay and Shankar called him "A son, a friend, someone very dear, and I love him very much."

Harrison was entranced by Indian philosophy and culture and encouraged the Beatles to meet the Maharishi Maresh Yogi and befriended the Radha Krishna Temple in London. He played with Indian musicians on "Within You Without You" for Sgt. Pepper in 1967.

When Shankar opened the Kinnara Music School in Los Angeles, one of his students was Robbie Krieger from the Doors. Shankar's influence can be heard on several Doors' tracks, notably "Light My Fire" and "The End".

Ravi Shankar appeared at the Monterey Pop Festival (1967) and Woodstock (1969) and gained a new, unexpected audience of admirers. Undoubtedly, many were stoned hippies, who found the drone of tambouras ideal accompaniment for tripping. Shankar was very uncomfortable when he saw the drug-sodden film, Chappaqua (1966) in which he was featured, and he would admonish audiences if he could smell marijuana as he was playing. He said, "I assured them that if they wanted to be high, I could make them feel high through the music, without drugs, if only they would give me a chance."

In 1971 Shankar asked Harrison to organise a benefit concert to alleviate the famine in Bangladesh. He had $10,000 in mind but the groundbreaking concert with Bob Dylan, Leon Russell, Shankar and Harrison raised $1m for Unicef's fund, although some of the money was in escrow for many years. Harrison's hit single, "Bangla Desh" begins with the words, "My friend came to me with sadness in his eyes", a reference to Shankar.

In 1974 Shankar worked with Harrison on Shankar, Family And Friends for Harrison's Dark Horse label, and they promoted it on a US tour. In 1987 Duane Eddy recorded "The Trembler", written by Eddy and Shankar with Harrison on slide guitar.

Shankar worked with jazz and classical musicians including John Coltrane, Yehudi Menuhin and Philip Glass and wrote the score for Gandhi (1982), but it is his influence on rock musicians that has had a marked effect on popular music. Shankar became a leading light in world music and must be applauded for encouraging the mix of music from different cultures. In 1965 we found those records strange but now they sound part of our multicultural society.

Robindro Shaunkor Chowdhury (Ravi Shankar), sitar-player and composer: born Varanasi, India 7 April 1920; Hon KBE 2001; married 1941 Annapurna Devi (marriage dissolved; one son, deceased), one daughter with Sue Jones, married 1989 Sukanya Rajan (one daughter); died La Jolla, California 11 December 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments