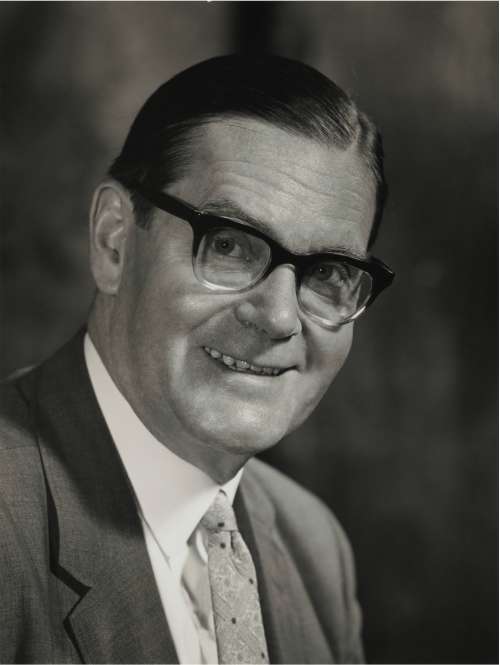

Professor Sir Francis Vallat: International lawyer, scholar and Legal Adviser to the Foreign Office

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Francis Vallat was an international lawyer of stature who straddled the worlds of government service, of academe, and of private practice with great aplomb over more than half a century.

He was born in St Quentin, near Reims; but despite his birthplace and French mother and middle name (Aimé), he was, like his father Frederick, very English. Frederick Vallat served in Mesopotamia and Persia during the First World War, and by the time of his demobilisation in 1919 had attained the rank of colonel. The English climate did not suit him and he bought a farm in Canada. The venture was not successful, however, and after he died in 1922 the family was left in relatively straightened circumstances.

But after a shaky start, Francis did well at school and eventually obtained a bursary and a prize which enabled him to study at the newly established Faculty of Law at the University of Toronto, whence he emerged with first class honours. He also developed a strong taste for sport, which stayed with him all his life.

On the strength of his achievements at Toronto, Vallat was able to go to Cambridge, where he read for the LLB and came under the influence of Arnold (later Lord) McNair, one of the towering figures in international law of the 20th century. With another first under his belt, he taught for a year at Bristol University and was also called to the Bar by Gray's Inn in 1935. He began a common-law practice, but the Second World War broke out and he served in the RAF Volunteer Reserve as a specialist in signals, attaining the rank of Flight Lieutenant.

After the war, he became an Assistant Legal Adviser at the Foreign Office, rising through the ranks until in 1960 he was appointed Legal Adviser. As was customary at the time, this appointment carried with it a KCMG, which he was awarded in 1962. He also became a QC in 1961.

Physically, Vallat was an imposing figure, very tall and substantial, with a dignified demeanour. This was useful in his diplomatic work: it meant that he was always noticed, and could often count on a degree of deference. There was, of course, much more to him than just his appearance. He had good judgement, and the prestige of his post ensured that he could expect to be listened to with attention by his peers abroad, if not always agreed with. He ran his department in a relatively relaxed way, unlike his predecessor, the eminent Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice, frequently delegating to what was, admittedly, a very able set of colleagues.

He was also an unusually enlightened head of department. When a female member of his team decided to get married, he managed to ensure that, contrary to her contractual terms, she did not have to resign; and during her short maternity leave saw to it that she was promoted and given an established appointment. Today this would be taken for granted, but not in those days or that place.

During his time at the Legal Advisers, Vallat appeared for the UK in a number of important cases at the International Court of Justice, including the seminal Certain Expenses of the United Nations (1962); in a case involving Cyprus in the European Commission of Human Rights; an arbitration between Greece and the United Kingdom; and in a fact-finding inquiry under the auspices of the Permanent Court of Arbitration. He was generally thought to have performed very effectively.

Vallat always retained a penchant for the academic life, and in 1965, most unusually, he took a year's sabbatical to become visiting professor and acting director at the Institute of Air and Space Law at McGill University – the most distinguished institution in that field. Furthermore, in 1968 he took early retirement from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (as it had become) and was appointed director of international law studies at King's College London, at first with the rank of senior lecturer, but with a readership and then professorship in short succession.

He wrote International Law and the Practitioner (1966) – a useful descriptive work that is still referred to – and edited An Introduction to the Study of Human Rights (1972), as well contributing a number of articles and essays to learned publications. His academic contribution was, however, less as a scholar than as a leader. He encouraged young talent, and was innovative in outlook. For instance, he played an important part in establishing, at King's, the first postgraduate course in the UK on the fledgling subject of human rights.

Vallat served as head of the UK delegation at the Vienna Conference on the Law of Treaties in 1968 and 1969, and performed other important official and semi-official functions for several years, even after he retired as a professor. Among other posts, he was director of studies of the International Law Association, a panel member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, and a member, and in due course vice-president, of the Curatorium of the Hague Academy of International Law.

He was a member of the International Law Commission of the United Nations from 1973 to 1981, and its chairman from 1977 to 1978. A number of distinguished British jurists had played a major part in the ILC's successful codification of the law of treaties, and so it was not surprising that Vallat was appointed Special Rapporteur on state succession in respect of treaties. That the codifying convention that emerged from this process was not a success, attracting few ratifications, is not a failure that can be laid at his door. The subject was simply too controversial politically, and any solution adopted would have left important groups of states dissatisfied. In 1982 he achieved the unusual distinction of a second knighthood, this time a GBE.

Following his retirement from the FCO, Vallat had also returned to practice at the Bar (becoming, in due course, a Bencher of Gray's Inn). Always a cautious lawyer, his eminence, coupled with his dignified and diplomatic demeanour, meant that his counsel was sought by governments from various parts of the world, some of whom he represented in the International Court of Justice in maritime boundary disputes and in inter-state arbitral proceedings. He was 88 when he made his last appearance as counsel in the ICJ, in the case of Maritime Delimitation and Territorial Questions between Qatar and Bahrain.

He was a jolly giant of a man, with a robust sense of humour. Sometimes this caused problems: his jokes could be quite personal, and some took offence. But it was meant in a friendly, teasing way, not maliciously; and despite his eminence, he received ripostes in the same vein in good spirit and often with a great roar of laughter.

In 1939 he married Mary Cockell, with whom he had a son and daughter who survive him. The marriage was dissolved in 1973, and he later married Patricia Anderson. They were a devoted couple for many years, and, when she died in 1995, his friends feared the worst. Fortunately, however, the couple had made friends with Lady Joan Parham, the widow of an admiral; and she and Francis married in 1996.

Maurice Mendelson

Francis Aimé Vallat, international lawyer: born St Quentin, France 25 May 1912; called to the Bar, Gray's Inn 1935, Bencher 1971; Assistant Lecturer, Bristol University 1935-36; Assistant Legal Adviser, Foreign Office 1945-50, Deputy Legal Adviser 1954-60, Legal Adviser 1960-68; QC 1961; KCMG 1962; Legal Adviser, UK Permanent Delegation to UN 1950-54; Director of International Law Studies, King's College London 1968-76, Reader 1969-70, Professor 1970-76 (Emeritus); Director of Studies, International Law Association 1969-73; married 1939 Mary Cockell (died 2004; one son, one daughter; marriage dissolved 1973), 1988 Patricia Morton Anderson (died 1995), 1996 Joan Parham; died Guildford 6 April 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments