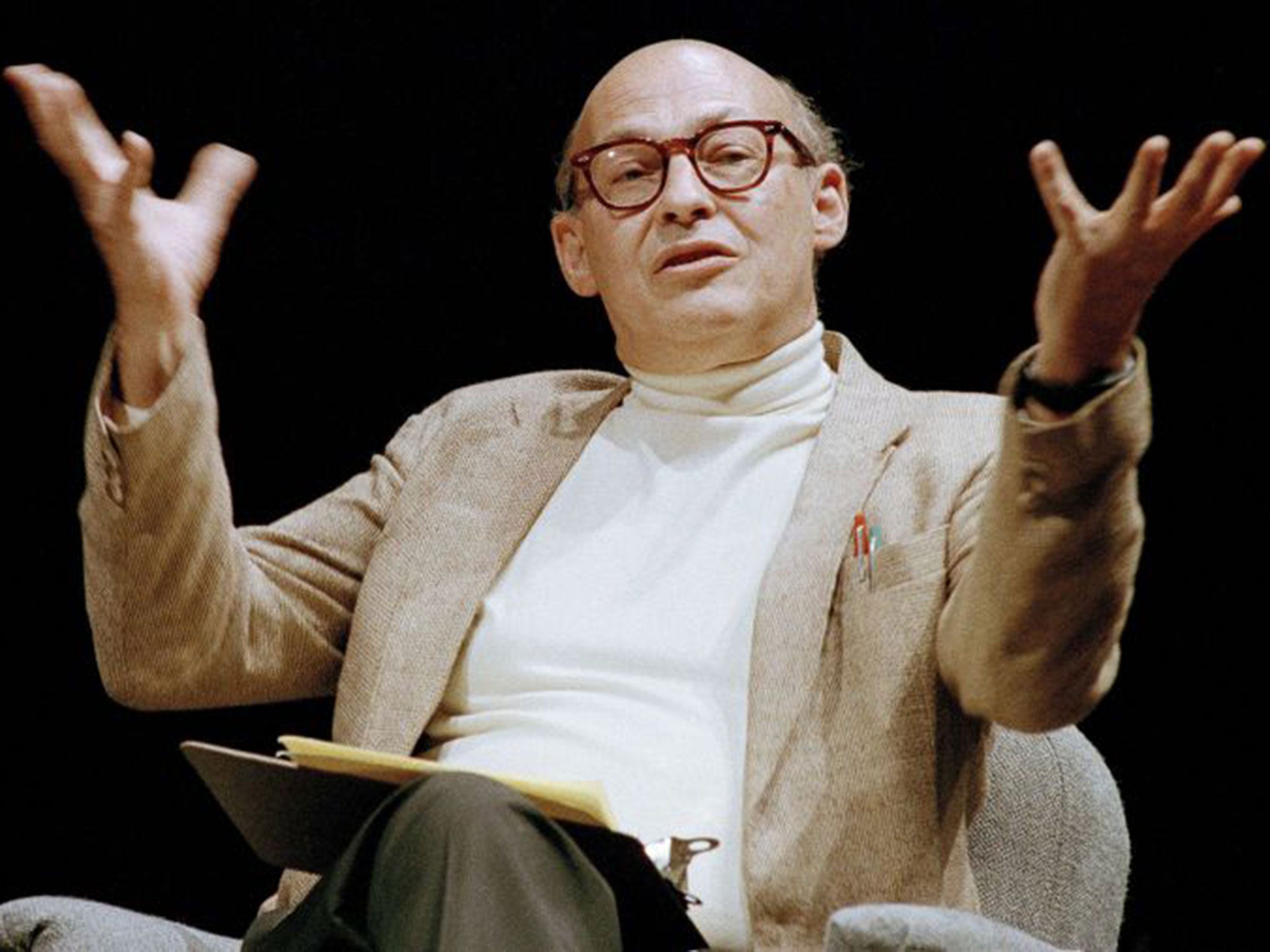

Professor Marvin Minsky: Mathematician and inventor inspired by Alan Turing to become a pioneer in the field of artificial intelligence

Minsky devoted his career to the hypothesis that engineers could someday create an intelligent machine

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Marvin Minsky was a founding father of the field of artificial intelligence and an innovative explorer of the mysteries of the human mind during his long tenure at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He was a professor emeritus at MIT's Media Lab, which has a broad, interdisciplinary mandate to explore technology, multimedia and design.

Minsky devoted his career to the hypothesis that engineers could someday create an intelligent machine. He flourished as a professor and mentor even as the field of AI endured discouraging results and eruptions of pessimism. He lived long enough to see AI ambitions flourishing anew, with attendant concerns about killer robots and rogue computers.

Although Minsky was himself an inventor – as a young man, he developed a microscope for studying brain tissue that eventually became a standard tool for scientists – his greatest contributions were theoretical. He developed a concept of intelligence as something that emerged from disparate mental agents acting in co-ordination. No single agent is intelligent when operating alone.

If a single word could encapsulate Minsky's career, it would be "multiplicities", his MIT colleague and former student Patrick Winston said. The word "intelligence," Minsky believed, was a "suitcase word", Winston said, because "you can stuff a lot of ideas into it." Other such words include "creativity" and "emotion".

Along with fellow AI pioneer John McCarthy, Minsky founded the artificial intelligence lab at MIT in 1959. His 1960 paper Steps Toward Artificial Intelligence laid out many of the routes researchers would take in the decades to come. He wrote, "we are on the threshold of an era that will be strongly influenced, and quite possibly dominated, by intelligent problem-solving machines." Anyone trying to mimic intelligence in a machine, he wrote, had to solve five categories of problems: search, pattern recognition, learning, planning and induction.

He also wrote books, including The Society of Mind (1986) and The Emotion Machine (2006), that colleagues consider essential to understanding the challenges in creating machine intelligence. On his death, his colleague Nicholas Negroponte wrote: "The world has lost one of its greatest minds in science. As a founding faculty member of the Media Lab he brought equal measures of humour and deep thinking, always seeing the world differently. He taught us that the difficult is often easy, but the easy can be really hard."

Minsky was born in New York in 1927. His father, Henry, was a noted eye surgeon while his mother, the former Fannie Reiser, was active in Zionist causes. As a child, he recalled, he was "physically terrorised" by playground bullies, and a lack of academic support in the classroom led his parents to enrol him in the progressive Fieldston School. His interest in electronics and chemistry blossomed, and he won a place at the prestigious Bronx High School of Science in 1941. He spent his senior year at a private Academy in Massachusetts, to bolster his college options. In 1945, he enlisted in the Navy in the final months of the Second World War and served in an electronics programme. He graduated in mathematics from Harvard in 1950 and received his PhD at Princeton in 1954.

At Princeton, with funding from the Office of Naval Research, Minsky co-built a primitive "electronic learning machine" with tubes and motors. He was also exposed to some of the greatest minds of the day, including John von Neumann, a pioneer of computers. Back at Harvard as a junior fellow in the mid-1950s, Minsky invented the confocal scanning microscope that would find many uses in science.

"Minsky's invention disappeared from view for many years because the lasers and computer power needed to make it really useful had not yet become available," Winston wrote. "About 10 years after the original patent expired, it started to become a standard tool in biology and materials science."

In 1956, when the very idea of a computer was only a couple of decades old, Minsky attended a two-month symposium at Dartmouth College that is considered the founding event in the field of artificial intelligence.

Minsky said last year that Alan Turing was the first person to bring respectability to the idea that machines might one day think. "There were science fiction people who made similar predictions, but no one took them seriously because their machines became intelligent by magic. Whereas Turing explained how the machines would work." In 1969 the US Association of Computing Machinery gave him the highest honour in computer science, the AM Turing Award.

Minsky and his wife, the former Gloria Rudisch, a paediatrician, enjoyed a partnership that began with their marriage in 1952. Their home became the regular haunt of science-fiction writers, including Isaac Asimov, while Richard Feynman, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist, would play the bongos at their parties.

Gloria Marvin recalled her first conversation with the man she ended up marrying: "He said he wanted to know about how the brain worked. I thought he is either very wise or very dumb. Fortunately it turned out to be the former."

Minsky acknowledged last year that he was disappointed that AI research has yet to create human-level intelligence in a machine. He said early efforts at large companies such as IBM failed to appreciate the complexity of the problem and how incremental progress would have to be. "It's interesting how few people understood what steps you'd have to go through," he said. "They aimed right for the top and they wasted everyone's time."

He was asked if he believed that machines will become more intelligent than human beings and if that would be a good thing. "Well, they'll certainly become faster," he said. "And there's so many stories of how things could go bad, but I don't see any way of taking them seriously because it's pretty hard to see why anybody would instal them on a large scale without a lot of testing."

Marvin Lee Minsky, scientist: born New York 9 August 1927; married Gloria Rudisch (three children); died Boston 24 January 2016.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments