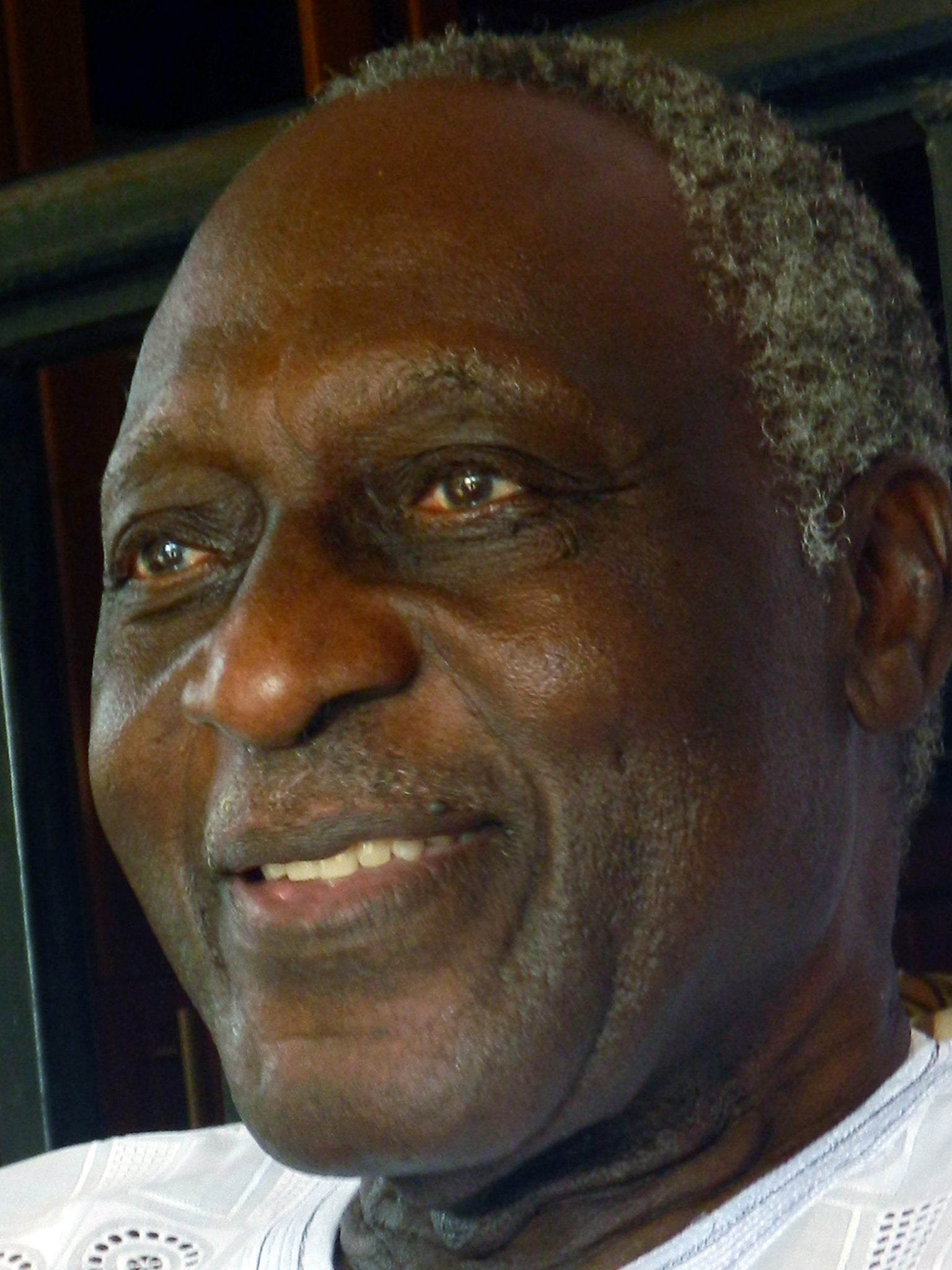

Professor Kofi Awoonor: Poet and novelist whose work fused the traditional and the modern

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The murder of the Ghanaian poet and novelist, Kofi Awoonor, in the Al-Shabab attack on a shopping mall in Nairobi would have appealed to his sense of the absurd. Awoonor, a fine figure of a man who did not physically reflect the 78 years at which his life was so brutally cut short, was in Kenya attending a literary festival. What was he going to buy in a mall that he did not already possess?

Perhaps that is an idle question. The terrible thing about organisations like Al-Shabaab is that they are by definition, random users of terror against people at whom they strike by chance. For all they knew, Awoonor, who was once Chair of the UN Committee Against Apartheid, might have been one of the few people on earth who understood the utter desperation that sometimes turns people into terrorists. But they riddled his body with bullets all the same. An absurd episode in an absurd life? Awoonor the poet would have relished the thought; and with his craftsmanship as a dramatist and film producer – he served as director of the Ghana Film Corporation and founded and directed the Ghana Playhouse – would have immortalised the "happenstance". Alas, all that is beyond him now.

Kofi Awoonor was born at Wheta, on the east coast of Ghana, close to the border with French-speaking Togo. The son of an Ewe mother, the daughter of a chieftain, and a tailor father with Sierra Leonean roots, he was christened George Awoonor Williams. He attended Ghana's premier secondary school, Achimota, and read English at the University of Ghana, Legon, pursuing further studies at the University of London and New York University at Stony Brook.

He had a good ear for languages, and in addition to his mother tongue, Ewe, he spoke the language spoken by a majority of Ghanaians, Akan, with a flawless accent in most of its dialects. The Ewe ethnic group is famed for its unusual deployment of rhythm in both song and dance, and Awoonor, with his gift for absorbing sounds, created English translations of the songs his people sang with as much music as he could inject into a foreign language.

His homeland is by the sea, which over the years has been filling up its lagoons and eating away at the land. It is a land of periodic floods, and the tragic aftermath of seasonal deluges provided Awoonor with rich material for metaphor, which he married to the assonance that invaded his ears whenever there was drumming and dancing in the Ewe villages. His work – poetry, novels and drama – incorporates African vernacular traditions, especially the dirge-song tradition of the Ewe people, into modern poetic form. His major themes, notably Christianity, exile and death, are sustained by repetition of key lines and phrases and by his use of extended rhythms.

His poetry, rooted in the oral poetry encountered during his upbringing, kept close to the vernacular rhythms of African speech and poetry. "It is for this reason I have sat at the feet of ancient poets whose medium is the voice and whose forum is the village square and the market place," he said.

I first met Awoonor at a conference of African writers in Kampala in 1962. This was a landmark conference: a budding Chinua Achebe was there, as was Wole Soyinka, who was yet to show any signs of winning the Nobel Prize for Literature. From South Africa came Ezekiel [Iskia] Mphahlele and Lewis Nkosi. Awoonor, who had preceded me to the conference, took me in hand and initiated me into the delectable aspects of life in Kampala. But he dissuaded me from invading his "turf" by maligning any lady who caught my fancy!

Nevertheless, when we returned to Ghana from the conference, we became great buddies. Awoonor even convinced me, as the editor of the Ghana edition of the Pan-African magazine, Drum, to take a trip with him to the border villages between Ghana and Togo, to see what irrational privations the "separated" peoples were subjected to.

We saw that the demarcation of the border had been done so haphazardly by the British and French that if the border line were to have been strictly observed it would have passed through people's kitchens and bathrooms. The ownership of chicken, sheep and goats that strayed across the "French line" would have had to be "verified" before they were allowed to be caught and taken back "home".

He went on to teach comparative literature at Stony Brook in New York before returning to Ghana in 1975 to teach at the University College of Cape Coast, but not long after he was arrested on charges of harbouring an army officer accused of involved in a plot to overthrow the government. He was imprisoned, but released after a few months, and he resumed teaching until 1982. He served as Ghana's ambassador to Brazil from 1984 to 1988 and as ambassador to Cuba from 1988, and was a United Nations envoy during the 1990-94 presidency of Jerry Rawlings.

The literary career which propelled Awoonor to prominence in Ghana began with a collection of poems, Rediscovery (1964), which was followed by Night of My Blood in 1971. There were also novels, including This Earth my Brother, an amalgam of prose and poetry which is probably his best-known book. He also delved into African oral literature in The Breast of the Earth (1975).

In the mean time, he was also influencing many young Ghanaians in his teaching at various institutions. He was always a political animal, and this led him into controversies and charges of opportunism. He disgraced himself in the eyes of non-Ewes when he wrote a piece criticising the Asante/Akan ethnic groups, though he had children with their some of their women.

He published his most significant works in the immediate post-independence period, including The House by the Sea (1978), which was influenced by the 10 months he spent in prison for alleged involvement in a coup. He was also the author of Rediscovery and Other Poems (1964), Night of My Blood (1971), Ride Me, Memory (1973), The Latin American and Caribbean Notebook (1992) and a volume of collected poems, Until the Morning After (1987).

When he died Awoonor was in Nairobi to take part in the Storymoja Hay Festival, a celebration of writing and storytelling and was due to perform on Saturday evening as part of a pan-African poetry showcase. his new book, Promise of Hope: New and Selected Poems, is to due be the lead book of the new African Poetry Book Series to appear early next year.

George Awoonor-Williams (Kofi Awoonor), writer, teacher and diplomat: born Wheta, Ghana 13 March 1935; married (six children); died Nairobi 21 September 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments