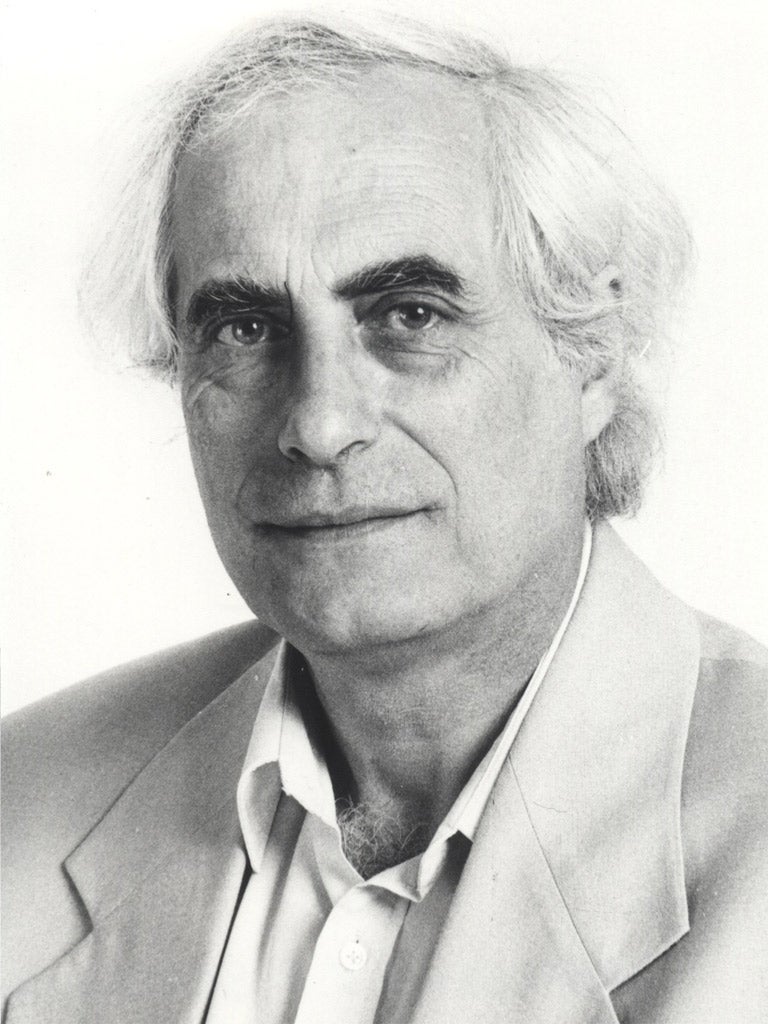

Professor Jacques Berthoud: Scholar of English and French lauded for his inspired teaching

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Despite the storm clouds of apartheid, an intellectual and cultural cross-traffic between Britain and South Africa flourished in adversity. One of the castaways was Jacques Berthoud, who arrived here in 1967. His coming, to teach first at the University of Southampton and then in 1979, as Professor of English and Related Literature, at York, had an electrifying effect on both universities. But it spread far beyond them, as the many students whom he inspired took what they had learned from him, never to be forgotten, and passed it on.

He was born not in South Africa, but at St Imier, near Neufchâtel, where his father was pastor; one of his ancestors was the great Ferdinand Berthoud, Harrison's rival as a maker of marine chronometers. When he was three his father became a missionary in Basutoland (now Lesotho), and his early years were spent at remote mission stations; formal schooling began at Morija primary mission school, from which he won a scholarship to Maritzburg College. After a year at the Collège Calvin at Geneva he returned to Maritzburg, his weekends spent with his uncle Edgar Brookes, Liberal senator and Professor of Political Science at the University of Natal, friend of Alan Paton and a formative influence on Berthoud.

He went on to the University of Witwatersrand, from which he graduated BA in 1956 (later BA Hons). Next year he met Astrid Titlestad, and they married in 1958. He taught English at the Johannesburg Trade School; his pupils were a mixed lot, and it was there that he discovered the power of King Lear to inspire profound discussion about the innermost springs of humanity. He also taught at the correspondence University of South Africa. Then in 1960 he got his first proper academic post, as a lecturer in English at the University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg.

There, he struck colleagues and pupils alike with the force of a warm, life-enhancing gale. His handsome figure and expressive face enlivened everything he did. Lectures on a text might begin with analysis, pursue meaning and purpose, then bring it home to the lives of his listeners, their social, political and emotional concerns. If it went on too long it would drift out of the lecture room into a long evening with a bottle of wine or music on his guitar. He could act, too: his Orsino in Twelfth Night enveloped the whole play. Politics were another matter: as an active member of the Liberal party, apartheid was increasingly abhorrent. Finally, he could bear it no more. FT Prince, poet and also South African, came to Pietermaritzburg and offered him a lectureship at Southampton, where he was professor. Berthoud did not wait.

Once there Berthoud discovered new gifts. He was not only an inspiring teacher; he was also an inventive administrator, taking on planning with the same passion and eye for detail he brought to literature. Only the lure of the chair in English and Related Literature led him on to York. He was bilingual, and the chance of extending his range to French was irresistible. Soon his seminars on Racine and Molière were attracting the same fascinated audience as his penetrating exploration of Conrad. The administrative skills learned at Southampton were soon in demand, and he became head of the department for 17 years, a measure of his skill and devotion to an arduous task. It was redeemed for him by his one-to-one contacts with postgraduate students, a mutual delight.

His energy overflowed in other directions. He became an active member of Amnesty International, and chairman of the British section in 1979-81. He loved art as much as literature and his influence was important in the formation of the York History of Art department. He was a brilliant orator, witty, pungent and moving, much in demand at degree and other ceremonies. He was a pillar of the York Bibliographic Society and worked tirelessly to bring the Laurence Sterne Trust and Sterne's last home, Shandy Hall, within the ambit of the University.

Six editions of Conrad, from The Nigger of the Narcissus (1984) to Nostromo (2007), were capped by his masterpiece, Joseph Conrad: the Major Phase (1978), which he was delighted to see translated into French. He also edited Phineas Finn and Titus Andronicus and wrote on the poet and playwright Uys Krige. He retired in 2002, deservedly Professor Emeritus. His last years were clouded with illness, but never his spirit. The wit, the loving enquiry that he brought to the needs and interests of all his pupils, the intellectual energy that irradiated all he did, will live on in the minds of all who knew him.

Nicolas Barker

Jacques Alexandre Berthoud, teacher and scholar: born St Imier, Switzerland 1 March 1935; married 1958 Astrid Titlestad (two daughters, one son); died York 29 October 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments