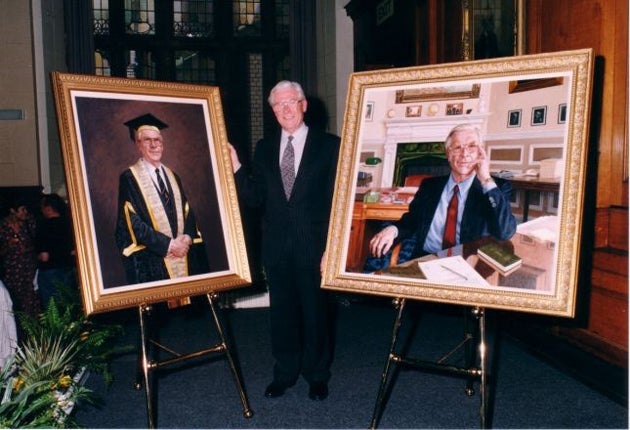

Professor Harold Hankins: Communications engineer who went on to lead UMIST to a position of academic eminence

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Harold Hankins had a distinguished professional career in both industry and academia. He began his working life as an engineer for the railways, giving him the later distinction of being the UK's only university boss to have completed an apprenticeship. During an industrial career at Metropolitan Vickers Electrical Company, he developed the first computer visual display system. He then embarked on a long career with the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST), where he continued his work on visual displays. A highly effective administrator, he was eventually to become Principal and first Vice-Chancellor of UMIST, leading it to a position of international pre-eminence during a time of unprecedented cuts in university funding.

Harold Hankins was born in 1930 in Crewe, growing up amid the wartime bombing raids and attending gramm-ar school. When he was 16, his father sent him to become an engineering apprentice in signals and communications with the London Midland and Scottish Railway Company. He was inspired by the great steam-locomotive engineer Sir William Stanier, who taught him that "the good engineer is immersed in every aspect of his field".

Enrolling in night school at the Manchester Technical College (later to become UMIST), he twice won a prestigious scholarship at the Institute of Electrical Engineers, and completed a first-class honours degree in 1955. Like many bright engineers of the time, he joined MetroVicks in Trafford Park, Manchester. These were exciting times in communications technology; Manchester University had recently developed the "Baby" computer and the Cold War had intensified. Hankins rose quickly to become assistant chief engineer, leading research teams on radio telemetry, radar computers, digital signal-processing, and visual displays.

By the mid-1960s, his team had developed a commercial visual display system for computers, familiar today but revolutionary then, and installed it at Oldbury power station. When MetroVicks became AEI, he led a team which developed and test-fired telemetry and guidance systems for deep space and rocket vehicles in the great Australian desert, including Blue Streak, Britain's satellite launch rocket.

Despite these engineering achievements, frustration at a lack of company recognition moved him to return to UMIST in 1968 as a lecturer, with a pay cut. Completing a doctorate in his spare time, he became a Professor of Communication Engineering in 1974. Having built up a large research group, he continued his work on visual-display systems, developing phosphors that allowed computer screens to be read in daylight and devising a system for displaying text and pictures simultaneously. He published more than 100 articles, patents and books, such work anticipating the computer revolution, and was later recognised when he received the Reginald Mitchell Gold Medal in 1989 and was made a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering in 1993.

But it was also in university administration that he was destined to excel. Appointed Director of the Medical Engineering Unit, he was made Head of Department of Electrical Engineering and Electronics in 1977. He became Vice Principal two years later, when the thunder clouds of approaching political change started to break and unleash a torrent of cuts in university funding.

His industrial career had taught him the value of recognising individual contribution, from shop floor to boardroom. Universities are communities of scholars dedicated to a search for the truth, and embrace a group of gifted but often eccentric and wayward individualists. The forging of a common sense of purpose in their destiny requires great skills in tact and sensitivity; reacting to and coping with painful change needs careful but firm leadership. Harold Hankins provided this, succeeding because he established a position of trust and care. Like his earlier predecessor Lord Bowden of Chesterfield, he was a perfect man for his time.

When he was appointed Acting Principal in 1982, UMIST was demoralised. By the time Hankins was appointed permanently in 1984, the UMIST block grant had been slashed 24 per cent over three years, while overseas student recruitment was severely hampered by high fees. As he told New Scientist at the time: "It's necessary now to have a principal who can get the best out of the academic machine during a period of level funding or worse, and also to raise income from industry for research". He instituted a series of tough money-saving measures, together with the first-ever five-year financial and academic plan for a UK university. Miraculously, compulsory redundancies were avoided. The Manchester Evening News was to describe him as the "ultimate Manchester Tech man", an accomplished leader of the very place in which he had been a student.

By the time of the first University Research Assessment Exercise in 1985, UMIST had comfortably risen under Hankins's leadership into the top 10 of the UK university league tables, an achievement which was built upon in 1989 and 1992. UMIST's block grant was significantly enhanced. More challenges arrived in 1992, with further cuts following the formation of the new universities from polytechnics, the advent of teaching assessment and staff appraisal, and the abolition of academic tenure. Hankins took this in his stride, by now achieving record research income as well as attracting high-quality students from home and overseas. UMIST received the Queen's Award for Export Achievement, the Queen's Anniversary Prize for Higher Education, and two Prince of Wales Awards for Innovation.

In 1992, UMIST became an autonomous university with its own degree-awarding powers, and Hankins became its first Vice-Chancellor. Before his retirement in 1995, he steered a major fund-raising campaign whose ultimate legacy was a new school of business and management and the Harold Hankins building on Oxford Road. By 1996, UMIST was the top-rated research university outside the London-Oxbridge triangle, and Hankins was awarded the CBE for services to higher education. He had already received Honorary Doctorates from UMIST, the University of Manchester, and the Open University, and was made an Honorary Fellow of Manchester Metropolitan University.

Outside UMIST, Hankins kept up a wide range of educational and industrial activities. He became chairman of the Manufacturing Institute in Trafford Park, committed to a charitable remit of "education for the public good with a particular emphasis on manufacturing". Even after he stood down to become honorary president in 2002, he led the conferment ceremony each year and showed great personal interest in the progress of the students. He succeeded the late Earl of Derby as president of Cheadle Hulme School for Girls, and was a non-executive director of both Thorn EMI and Bodycote International plc, administering its education foundation. Always an enthusiastic engineer, he was also a member of the Parliamentary Scientific Committee, a member of the Engineering Council and local chairman of the Institute of Electrical Engineers.

His passion in later life became military history, particularly that of the Officer Training Corps (OTC) of UMIST during the First World War. Feeling a genuine debt to those officers, with one of his sons he photographed the graves and memorial inscriptions of the 196 UMIST officers who fell in northern France, Belgium and beyond. He wrote a definitive historical text on the Manchester and Salford Universities OTC, and was made an honorary colonel and chairman of their military education committee, often accompanying them on summer training camps.

Harold Hankins always encouraged students and young people to realise their talents and gifts. Professor Ken Entwistle, a friend and colleague, said of him: "He will be remembered for his kindness and modesty, and for his command of loyalty from all sectors of UMIST and beyond, through a capacity to preserve a calm, unperturbed and fair-minded mien in the midst of grievous problems and turbulent debates".

Nicholas Hankins

Your obituary of Harold Hankins (2 July), former vice-chancellor of UMIST, was accurate in highlighting his administrative talents, writes Dr Anthony Carew. He took charge during the worst possible crisis and completely turned the Institute around. It wasn't just the crippling cuts in grants imposed under Thatcherism that posed the challenge. His predecessor had been forced out following staff protests at spending on the official residence when jobs were under threat.

Morale was rock bottom. Hankins changed all that. The residence was disposed of, and he made his employees' welfare his top priority. Avoiding compulsory redundancies was not, as the obituary suggests, a "miracle". It was a fundamental policy that underpinned his entire approach to dealing with staff. This was a rare vice-chancellor who was proud to talk of his membership of the Amalgamated Engineering Union, and people soon came to recognise him as a different kind of university boss.

One of his first announcements was that the two official Daimlers would be replaced by a Ford Escort. He next announced that he would not be using the car since he travelled by public transport. The car would be available for use by staff around Manchester. That set the tone. He made a point of eating in the staff canteen; urged people to stop him on the campus and have a word, and maintained an open-door policy for people wanting to discuss their problems with him.

He had little use for the managerialism that was then beginning to take hold in universities and now blights the sector. Plain dealing with the campus unions and treating people as valued colleagues were the simple rule. And everyone, whatever their grade, knew him and referred to him with affection as "Harold".

Harold Charles Arthur Hankins, engineer and university Vice-Chancellor: born Crewe, Cheshire 18 October 1930; Lecturer, University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology, 1968-1971, Senior Lecturer 1971-1975, Professor of Communication Engineering, and Director of Medical Engineering Unit 1974-84, Head of Electrical Engineering and Electronics, 1977-1980, Vice-Principal, Deputy Principal and Acting Principal, 1979-1984; Principal 1984-1992; Vice-Chancellor 1992-1995; Fellow of the Institution of Electrical Engineers, 1975; Fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering, 1993; CBE 1996; married 1955 Kathleen Higginbottom (three sons); died Glossop, Derbyshire 2 May 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments