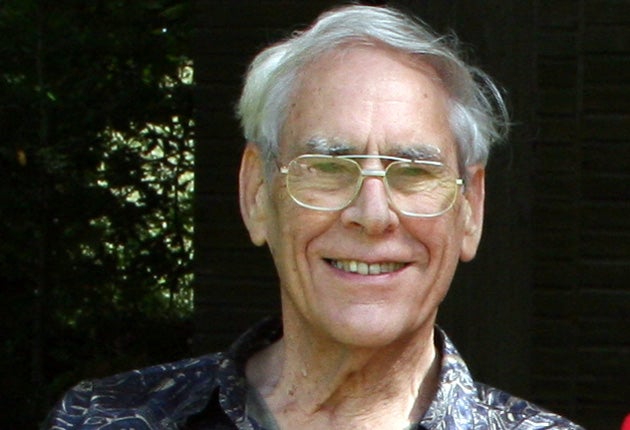

Professor David Morley: Pioneer in children's health care for more than half a century

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.David Morley was a driving force for children's health worldwide for more than 50 years, active until the end of his life in advocating the key themes of his career: growth and nutrition, the involvement of parents and children in their own health care, and health-worker education. To many thousands of health professionals around the world he was a very special person: an idealist who practised what he preached and a charismatic role model and teacher. From his early days he believed in a bottom-up rather than a top-down approach, in offering rather than withholding knowledge, and in the empowerment of parents to be the key health workers.

David Cornelius Morley was born in 1923, the youngest of six children of a vicar. Educated at Marlborough and Cambridge after being told that he was not bright enough for the clergy, David was a wartime medical student but after graduation in 1947 was sent for national service in Singapore and Malaysia. Showing an interest in flying, his early visionary approach was noted by his instructor who discouraged him, saying that his mind was on higher things and "his landings were always two feet above where they were supposed to be".

In 1951 Morley moved to the north to work in Sunderland, where he met his future wife, Aileen Leyburn, then a ward sister, and in 1953 he moved to Newcastle to work with Professor James Spence and Donald Court. The former was the instigator of the first long-term study of children in England, the 100 families study, which examined the effect of the home and social circumstances on health and disease, a concept close to Morley's heart. His second mentor, Court, went on to be Professor of Child Health after Spence and in the 1970s redesigned and integrated child-health services following his seminal report, "Fit for the Future".

The route from Newcastle to the developing world later became well-worn, but Morley was the first to pursue it. In 1956 he took up a post that linked research with service, in Ilesha, Nigeria. Over the following five years his work laid out the pattern for the rest of his life and he is still remembered fondly there for his achievements. In Ilesha, Morley developed the interests that remained lifelong: measles, and its relationship with malnutrition, and growth monitoring. Following the example set by Spence in Newcastle, he carried out the first longitudinal study in Africa, of all the babies born in the village of Imesi. This led to the development (invention is a better word) of the "Road to health" chart – a growth curve showing the anticipated growth of a child under five. Each weight is marked on the curve and a fall-off – the first sign of malnutrition – is detected early. These charts were given to mothers to keep at home, a revolutionary notion at the time, but since copied all over the world. The latest WHO charts based on breast-fed babies are now part of the UK personal child-health record – an innovation Morley introduced more than 50 years ago.

After his return from Nigeria in 1961, Morley worked at the London School of Hygiene and moved to St Albans. The next important step came in 1965 with the establishment of Teaching Aids at Low Cost (Talc) – a name which became familiar all over the world, since this was a charity which sent out educational materials (slide sets, books and later, CD-roms) to centres where education was essential but teaching aids non-existent. Talc has gone on to be a global success story and there is hardly a hospital or clinic in the world that has not made use of its materials.

From then on, teaching became Morley's chief interest, and he went to the Institute of Child Health in 1964 to head the Tropical Child Health Unit and established, with Zef Ebrahim, the WHO/Unicef course for senior teachers of child health. This later became a master's course in mother and child health, and brought together the teaching about the health of the mother with that of the child – a key connection that is still made all too seldom. This course later re-built the Newcastle link by sending the students (who included nurses and nutritionists as well as doctors) north for a research project in a city which at that time had many third world connotations. Students went on to be influential figures in maternal and child health all over the world, and were visited by Morley and Ebrahim, and often included in outreach research or in the development of ideas designed in the kitchen at St Albans.

The years leading up to Morley's official retirement in 1989 were filled with ideas, experimentation and innovation in relation to intermediate technology, growth-monitoring and teaching. His first book, Paediatric Priorities in the Developing World, later to be the bible for health workers in rural settings, came out in 1973 and was distinctly different from the usual disease-centred book as it brought together prevention with cure and highlighted the importance of emotional as well as physical development in young children.

In 1978, the International Year of the Child, Morley developed, with Hugh Hawes of the Institute of Education, the Child to Child programme: children acting as health teachers for their younger siblings. This concept later came to be prominent through the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989. New ideas flowed freely: the double-ended spoon (for salt and sugar) to allow mothers to treat dehydration at home; the mid-arm circumference strip to measure malnutrition in a rural setting; the robust Talc weighing scale which could be used by parents; the technique of sterilising water by placing it in sunlight. And growth-monitoring was included as one of the core features of the Unicef child survival programme Gobi (growth monitoring, oral rehydration, breast feeding, immunisation).

Morley was awarded the James Spence medal of the British Paediatric Association (now Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health) in 1983 and the CBE in 1988, but was not a man to relish honours; his greatest pleasure was the success of a mother in feeding her child, or a health worker learning a new skill. His influence and philosophy of primary health care, health-professional education, community development, parent and child empowerment, and intermediate technology will last through the centuries.

Tony Waterston

David Cornelius Morley, paediatrician and health care activist: born Rothwell, Northamptonshire 15 June 1932; married 1952 Aileen Leyburn (two sons, one daughter); CBE 1989; died Weymouth, Dorset 2 July 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments