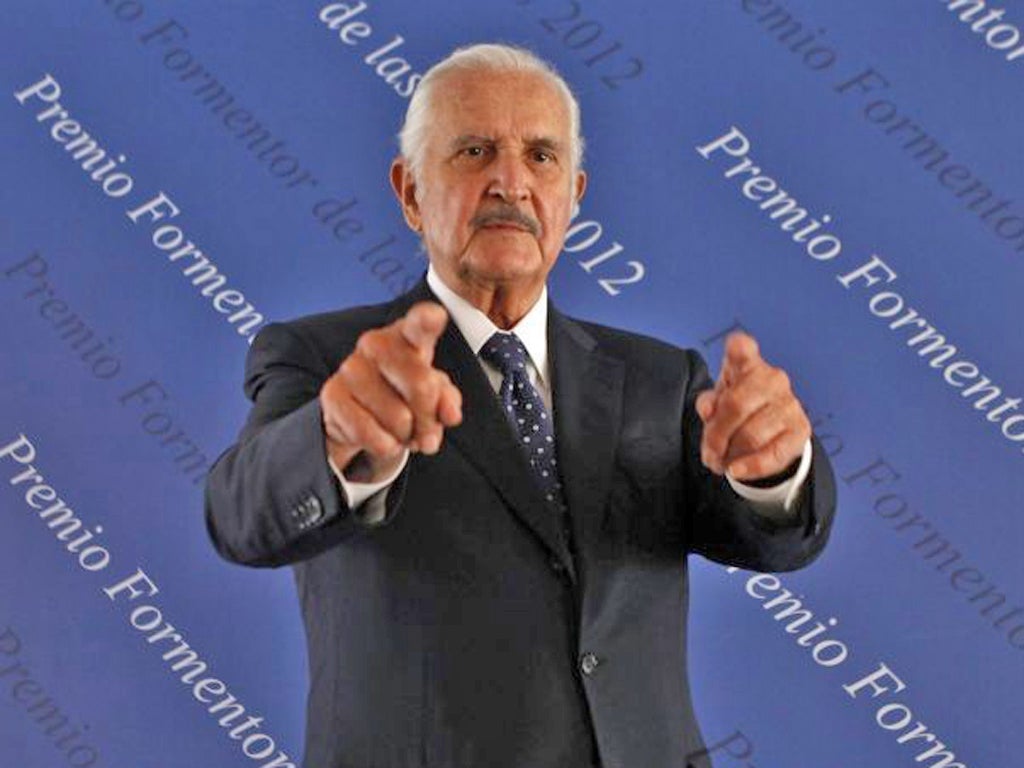

Professor Carlos Fuentes: Author whose work fuelled the rise of South American writing

'I have learned to write anywhere,' he said – 'on an aeroplane, on a bus, a Mexican bus full of bananas...'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is an abiding mystery why the Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes was never awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. A major 20th century literary figure, he launched "el boom" in Latin American fiction with his first novel, Where The Air is Clear (1958), while his magnum opus, Terra Nostra (1975), is one of the great novels of the 20th century. Some critics rate The Death of Artemio Cruz (1962) and his later novel The Years of Laura Diaz (1999) as Terra Nostra's equal.

The one-time Mexican ambassador to France and Harvard professor was also a high-profile critic of the US's policy towards Latin America and an acute analyst of his own country's problems. He moved among presidents, film stars and other world-ranking artists. He was close friends with Luis Buñuel, collaborated on film scripts with Gabriel Garcia Marquez, had an affair with the actress Jean Seberg and numbered among his friends Milan Kundera, Arthur Miller and Mario Vargas Lhosa.

As a Latin American writer he was often lazily bracketed with Marquez, Lhosa and the other "magical realists". He did something different, however. Some critics have argued that he has more in common with European modernists such as Joyce, Woolf, and Proust: The Death of Artemio Cruz was just about the first Latin American novel to employ stream of consciousness. He was dubbed "the Balzac of Mexico", and, he said, "Balzac travelled between documentary realism and stories of the fantastic with the greatest of ease."

Fuentes came from a well-to-do family of German and Spanish descent. His father, Rafael Fuentes Boettiger, was a liberal lawyer, his mother, Berta Macias Rivas, a staunch Catholic. Fuentes was born in Panama City, where Boettiger began his diplomatic career. Fuentes was educated in private schools across the Americas; for much of the 1930s the family lived in Washington.

His mother insisted he speak Spanish at home but Fuentes was quite the little North American, imbued with a Calvinist work ethic. At the age of seven he started a magazine in English made up of his drawings, book reviews and bits of news. He circulated the single copy round his apartment building. His reading was voracious but he said his greatest influence was the stories his grandmothers told him: "Grandmothers are the best novelists in the world."

In 1944 his father was posted to Buenos Aires, where Carlos lost his virginity to a neighbour – "a beautiful Czech woman, aged 30, whose husband was a film producer". He also discovered Jorge Luis Borges: "Borges gave Latin American writers a consciousness of our tradition. He pointed out that the Spanish tradition is not only Christian, it is Arab and Jewish too. That was important to me." It was to become a major strand in Terra Nostra.

He decided to write in Spanish: "Although the English language didn't need another writer, the Spanish language did." Under pressure from his family he gained a law degree, and in 1950 went to Switzerland to do postgraduate work. When he returned to Mexico in 1954 his first collection of short stories, The Masked God, was published. With Octavio Paz he founded Revista Mexicana de Literatura, the first of several magazines he edited.

He worked in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, then as head of the department of cultural relations. By then his first novel, Where The Air Is Clear (1958), had been published. Harking back to the Mexico City of his teenage years, when it was known for its translucent air, it heralded "El Boom" in Latin-American literature and was translated into 25 languages. Its success allowed him to write full-time, but, Fuentes remembered, "It was received by the most horrible collection of critical catcalls in Mexican history." His circle of friends by now included Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Luis Buñuel. In the early 1960s he and Marquez wrote film scripts "to make money for serious writing".

In 1959 he married Rita Macedo, a celebrated actress who starred in Buñuel's film The Exterminating Angel. They had their first child, Cecilia, in 1962. His second novel, The Good Conscience, about the clash between a young man's adolescence and his family's materialism, had been published the year before. His third, The Death of Artemio Cruz (1962), confirmed his stature. He addressed a theme he would return to – the promise and failure of the Mexican Revolution of 1910. In the same year he published the novella Aura, an atmospheric, gently erotic ghost story.

Fuentes's public backing for Castro in 1959 made him persona non grata in the US and he spent much of the 1960s in Europe; he and Macedo divorced and he moved to Paris. His next novel, A Change of Skin, (1968) had mixed reviews. That year Fuentes witnessed the student uprisings in Paris, travelled with Marquez to Czechoslovakia at Milan Kundera's invitation and denounced the Soviet invasion. He also condemned the Tlatelolco massacre of protesting students by troops just before the Mexico Olympics.

At a New Year's Eve party in 1969 he met the American actress Jean Seberg, in Mexico to film a tequila western. They had a "passionate location romance". The following year his father died and in 1974 Fuentes became Mexican ambassador to France. Earlier that year, Fuentes had a daughter, Natasha, by his second wife, Sylvia Lemus, a TV presenter. Natasha was to die of a heart attack. In 1975 came a son, Carlos, who was diagnosed a haemophiliac.

In that same year, Fuentes's masterpiece, Terra Nostra, was published. Its origins lay in his first visit to Spain, in 1967. He had visited the Moorish Alhambra and Philip II's Escorial. "The Moorish palace was open and airy, full of flowers and light; the Escorial was a mausoleum, turned in on itself." He saw this as a symbol of Spain's history – "an accumulation of contradictions ... That is why my chief stylistic device in Terra Nostra is to follow every statement by a counterstatement and every image by its opposite."

Terra Nostra is in the baroque tradition of which Alejo Carpentier was the most famous exponent. It has fantastical elements, re-imagined history and an acute realism. "Buñuel told me that if I wanted to keep the fantastic element alive, to make the surrealism tolerable, I would have to buttress the fantasy with a great deal of hard detail and specific information ... It presents an enigma, whose solution is another enigma. This is the function of art – to ask questions, not to answer them."

He resigned as ambassador in 1977 in protest at the appointment as ambassador to Spain of the former president Gustavo Diaz Ordaz, the man most implicated in the Tlatelolco massacre. He accepted a range of university posts in North America while continuing to be a critic of the US's Latin American policies. His 1985 novella The Old Gringo, a beautifully written account of Ambrose Bierce's disappearance in Mexico, clearly expressed Fuente's ambivalence towards Mexico's overbearing neighbour. (He was disappointed in the Jane Fonda film version.)

In 1987 Fuentes became Harvard's first Robert Kennedy Professor of Latin American Studies. And he produced a novel of such exuberant energy you might have expected it to be written by someone 30 years younger.

For Christopher Unborn (1987) – a rattle-bag of modernist and post-modernist devices – he pillaged his own novels, Conrad, Quixote, Kafka and those Mexican boy-wonder writers of the late 1960s who had made rock lyrics, street slang and slum life part of Mexico's literary tradition. "Art is made out of communication not isolation," he said. "Not purity, not originality. I refute the concept of originality in literature."

Of the novel's setting he said: "I hope my writing about the death of Mexico City in Christopher Unborn is exorcism, not prophecy. In my time I have seen the death of several Mexico Cities. I still have a great nostalgia for a city where the air is clear."

He was 60 in 1988 and celebrated with Myself with Others, a selection of essays that showed the range of his interests: Cervantes, Diderot, Gogol, Buñuel, Borges, Kundera and 20th century politics. Octavio Paz, a friend since they had met in Paris in 1950, had a different birthday present. His magazine Vuelta printed a vicious attack on Fuentes's work. The two men never spoke again.

Fuentes's appetite for writing got bigger once he reached 60. "Writing is absolutely my human condition. I must write. I have learned to write anywhere – in an aeroplane, a hotel room, a bus – a Mexican bus full of bananas. I don't care." He would write from 8am to 1pm, "then the rest of the time is free for other things – reading, politics, making love."

The 1990s started with a flurry of publications: Constancia: and Other Stories for Virgins (1990); The Campaign (1991), the first of a planned trilogy spanning the 100 years between the 1810 Year of Revolution and the 1910 Mexican Revolution; and The Buried Mirror (1991), a wide-ranging account of Hispanic culture. The latter accompanied a BBC TV series Fuentes wrote and presented. He bought a flat in London and thereafter he and his wife split their time between Mexico City and London. His son Carlos had grown up to be an accomplished artist and poet. However, in 1994 illness rendered him almost blind and deaf, and he died in 1999.

The same year, Fuentes received a lot of media coverage for Diana: The Goddess Who Hunts Alone, a thinly fictionalised account of his affair with Jean Seberg. Typically, its publication coincided with A New Time For Mexico, a reflection on the governing of Mexico and the problems the nation faced. In 1995 The Crystal Frontier was a pared-down novel in nine stories about Latinos crossing the Rio Grande. In the same year he wrote an illuminating introduction to the diaries of Frida Kahlo.

As he approached 70 he embarked on a novel as ambitious as Terra Nostra. The Years With Laura Diaz was a "counterpoint" to The Death of Artemio Cruz. "I always felt a little worm inside me: Now you need to write a novel with a woman protagonist." He also wanted to write about his grandmothers, his poet uncle and his own son. Writing about his son was "an act of exorcism".

"Every book is an act of exorcism, in the hope that what I write about doesn't come to pass," he said. But exorcism can turn to prophecy. "All the evils of Mexico City I tried to exorcise in Christopher Unborn came true with a bonus: pollution, crime, corruption."

Increasingly, his work was inspired by his memories. "When I reached 60, the Proustian worm started tickling my belly." His 16th novel, Inez, came from that "marvellous year" in Buenos Aires in 1944 when, in addition to women and Borges, he had discovered opera.

In the new millennium the books kept flowing. In This I Believe was written in the form of a dictionary. The Eagle's Throne (2003), overtly political, was suggested by a conversation with Bill Clinton and allowed Fuentes, always interested in literary form, to write an epistolary novel.

Fuentes was weighed down with prizes, awards and honorary degrees. They included the Cervantes Prize, the Mexican National Award for Literature and the Legion d'Honneur. His passion for writing never diminished, though his reasons might have changed: "You start by writing so as to live and you end up by writing so as not to die."

Carlos Fuentes, writer and diplomat: born Panama City 11 November 1928; married 1957 (marriage dissolved; one daughter), 1973 Sylvia Lemus (one son deceased, one daughter deceased); died Mexico City 15 May 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments