Prince Philip obituary: Father, naval officer and consort

Once an abandoned aristocrat, Philip married the Queen in 1947, just a few short years before she came to power

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Once, late in his life, Prince Philip was involved in a discussion of the problems experienced by adopted children and the point was made to him that they can be haunted by uncertainty about who they really are. He listened and after a moment’s reflection observed: “I never knew who I was.”

Coming from a man famous – notorious, even – for his iron certainties, whose veins flowed with some of the bluest blood in Europe and whose face and name were among the fixtures of British life for more than half a century, such words may be unexpected, but they were amply justified by his experience.

So chronic were his problems of identity as a child and young man that when in 1947 he became engaged to the heiress to the British throne this great-great-grandson of Queen Victoria was technically a commoner who was just getting used to a brand new name and a new nationality.

And married life brought him endless confusions of its own, not only about titles and names (was he a prince? Was he a consort? Was he a Windsor?) but also about roles and remits, powers and protocol. As husband of the Queen he occupied a permanent constitutional grey area.

These uncertainties had their consequences. They brought out a determination and an ability to adapt, which allowed him to make a true success of his difficult position – Prince Philip, who has died aged 99, made a substantial mark on British and international life, across an unexpectedly wide field. At the same time, they bred in him a steeliness that cannot have failed to contribute to the notorious difficulties experienced by his children in their personal lives, difficulties which corroded the monarchy he wanted to strengthen.

His early life, while colourful, has some of the qualities of a family horror story. He was born in Corfu on 10 June 1921, the fifth child and only son of Prince Andrew of Greece and his wife Alice, who was the sister of Lord “Dickie” Mountbatten. A prince of the royal houses of both Denmark and Greece, he bore the magnificent full name of Philip (“Philippos” in Greek) Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg.

When he was only 18 months old, his father, a military man, was suddenly made the scapegoat for Greece’s calamitous defeats in Turkey and was saved from the firing squad only by British diplomacy personally instigated by George V. The family was spirited away in a British warship and legend has it that, so great was their haste, little Philip was carried aboard in an orange box.

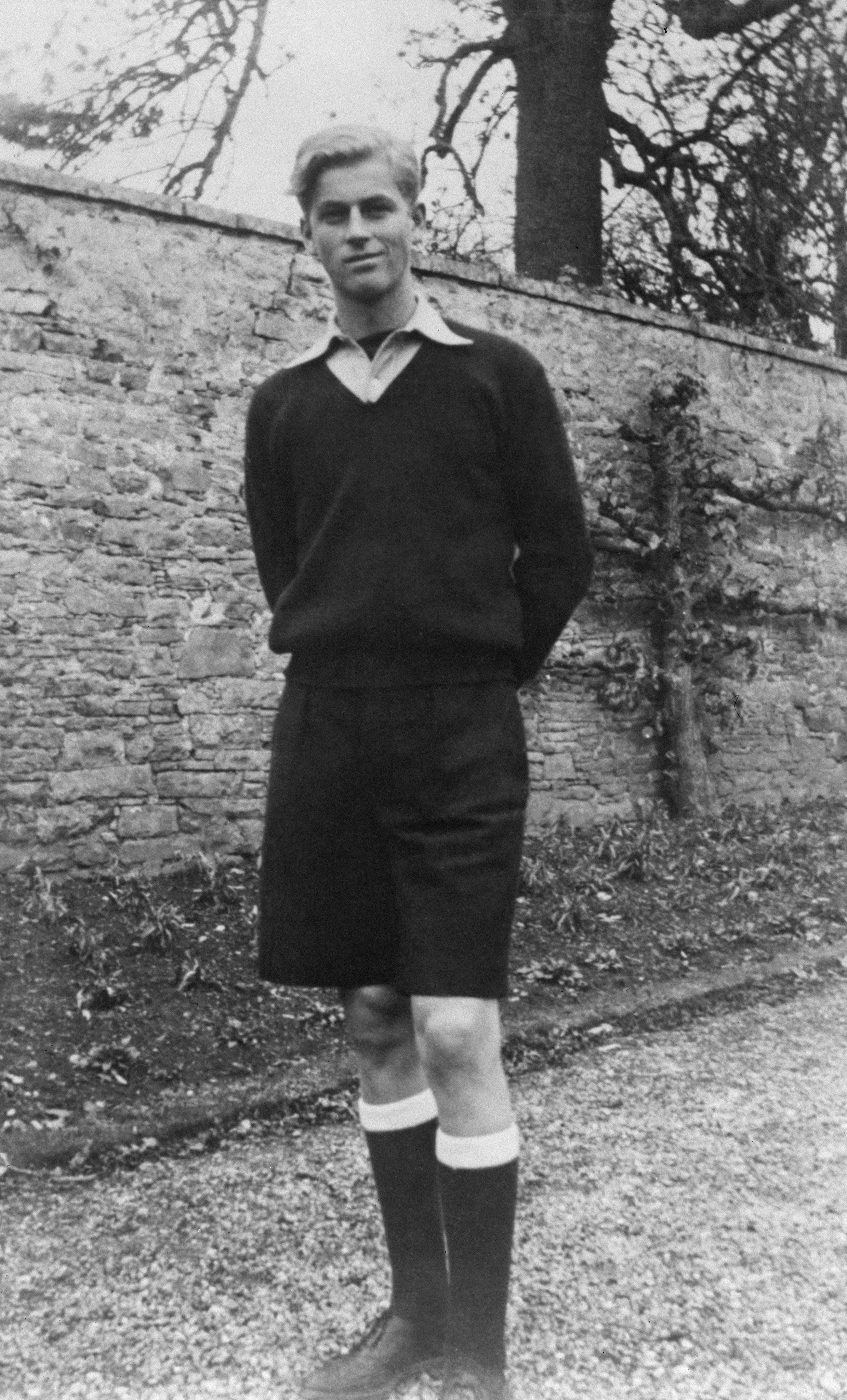

In straitened circumstances, they settled outside Paris in a house owned by an uncle, where Philip was reared largely by his older sisters and in due course sent to an American-run school. When he was nine years old, however, an extraordinary series of events effectively left the little blond boy without home or family.

His mother, having first undergone a profound religious experience, suffered a nervous breakdown which confined her to mental institutions for years; his sisters, in rapid succession, all married German aristocrats and departed to their various Schlosses; and his father, already poisoned by bitterness at his treatment in Greece, abruptly decided his marriage and his involvement with the family were at an end.

Young Philip was left as a piece of aristocratic flotsam on the face of Europe and he was fortunate that through the influence of his mother’s mother, the Marchioness of Milford Haven, he found his way to Cheam prep school on the outskirts of London. He would embrace this stable, institutional existence with enthusiasm – it can be said, in fact, that he never subsequently left the shelter of institutions of one kind or another.

From Cheam, where he excelled at games and made little impression at schoolwork, he graduated to Salem in Bavaria, an experimental school run by the charismatic Kurt Hahn where leadership, independence of spirit and a general hardiness were prized above all. When Hahn, a Jew, fled the Nazis and set up at Gordonstoun in Scotland, Philip followed.

Now in his teens, he was tall, fit, handsome and tough, in many ways the Hahn ideal. His schoolmates noted that he stood firmly on his own feet and never played the card of privilege; they knew him simply as Philip. Some, however, were aware that holidays presented him with a problem.

“He did have a terribly sad background,” one friend with whom he stayed would later recall. “He had no home to go to, nobody to kiss him goodnight, nobody to help him pack his trunk, nobody to take him back to school...” He himself looked back with something like disbelief: “It really is amazing that I was left to cross a continent myself – taxis, trains, boats – to get to my sisters’ homes in Germany.”

He had no home to go to, nobody to kiss him goodnight, nobody to help him pack his trunk, nobody to take him back to school

In May 1939, aged 18, Philip joined the royal navy at Dartmouth and seven months later was at war, a midshipman on a battleship in the Pacific. Soon he was switched to the Mediterranean, where he was mentioned in dispatches for cool management of his ship’s searchlights during the Battle of Matapan, contributing to the night-time sinking of two enemy cruisers. He went on to a spell of convoy duty in the North Sea and then returned to the Pacific in a destroyer in 1945, just in time to witness the Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay.

He always dismissed suggestions he was a war hero, classing himself among “those who followed” in the conflict. “Our only distinction,” he said once, “is that we did what we were told to do, to the very best of our ability, and kept on doing it.” This was a shade too modest, for he was an outstanding young officer who was promoted extremely rapidly (and, in the estimation of contemporaries, entirely on merit).

It is clear that marriage to Princess Elizabeth was on the cards for Philip even before he returned to peacetime Britain in 1946. They had first met when she visited Dartmouth in 1939, an encounter subsequently imbued with romantic overtones that are hard to credit given that she was just 13 at the time.

The liaison really developed four or five years later, by which time she was a young woman and he was paying occasional social visits to Windsor Castle during shore leave (he knew the king as “Uncle Bertie”). It is said that the princess kept a framed photograph of him in her apartments.

In 1946, the king and queen believed their daughter was a little young to marry and sought a delay, and in the interval something was done about the young man’s troublesome identity. Rather belatedly, considering his seven years’ service in the navy, he became a British subject, and after high-level consultations took the name “Lt Philip Mountbatten RN”.

This was a symbolic leap. His father had died penniless in the arms of a mistress in Monte Carlo in 1944 and his mother, now restored to health, was a Greek Orthodox nun. Of his sisters in Germany, one had died in an air crash in 1937 and though he maintained links to the others it was difficult – two of the brothers-in-law had for a time been active Nazis. Now he, the landless, rootless only son, had effectively renounced his Greek past and at least in British terms was no longer even a prince.

It was thus as a new-made man, a conveniently blank sheet, that he married Princess Elizabeth at Westminster Abbey in November 1947 in a ceremony described by Churchill as “a flash of colour on the long road we have to travel”. On the same day, the groom became Duke of Edinburgh. (He was made a prince again only in 1957.)

With George VI still only in his fifties, the couple expected to enjoy many years of relative quiet. Philip, pursuing his naval career, was posted to the Mediterranean and for a spell Elizabeth even joined him as a navy wife in Malta, but the king’s health declined rapidly and he died in early 1952.

When the news was broken to Philip – famously the couple were at Treetops in Kenya – it was said that “he looked as if you’d dropped half the world on him”. He knew instantly that he had to leave the navy – where in other circumstances he would certainly have achieved very high rank – and accept at the age of 31 the life of a constitutional appendix.

When the news was broken to Philip – famously the couple were at Treetops in Kenya – it was said that ‘he looked as if you’d dropped half the world on him’

There was no possibility of becoming another Prince Albert because 20th century Britain would not swallow a politically powerful royal consort, and nor could he live an independent life, with a career in business for example. At the same time, neither he nor the public would accept a life of idleness.

So he invented a role for himself and he did so at first in the teeth of establishment opposition. Churchill, for one, disliked him at first and was suspicious of his closeness to Lord Mountbatten, while senior courtiers strove to marginalise and even disparage him. To overcome this he drew on the self-reliance and toughness learned in a lonely upbringing — he was, in the words of the historian Ben Pimlott, “in awe of nobody”.

Over time he would prove a powerful modernising force in the monarchy, easing protocol, opening doors and building bridges to groups previously neglected, notably in industry, science, technology, sport, youth, housing, the environment and religions other than the Church of England.

He also brought a new quality to this engagement, for he was rarely content to be a figurehead. When he was president of a body, anything done in his name had to satisfy his high standards first; when there were meetings he always wanted to be there, to be fully briefed, to express his views and, if possible, to get his way.

He brought to this work an abrasiveness, impatience and naval saltiness which could occasionally let him down, particularly when the media were involved, and so was built his reputation for tasteless indiscretion. His jokes often failed to travel, as when he remarked to a South American dictator that it was “a pleasant change to be in a country that isn’t ruled by its people”, or to a British student in China about the danger of becoming “slitty-eyed”.

He did not always hide his views on the media. On a visit to Gibraltar, he surveyed the Rock’s most famous residents and the press photographers beyond them and asked aloud: “Which ones are the monkeys?”

From the 1980s onwards, however, it was his role as a parent rather than a source of “gaffes” that came under scrutiny, as the next generation of his family became embroiled in scandal after scandal. Philip was cast as a cold father at least partly to blame for his children’s emotional difficulties.

How far this was true is impossible for any outsider to measure. Certainly he was diffident and distant at home, and also ill-tempered and occasionally bullying, even towards his wife. He was especially hard on Prince Charles, whom as a boy he regarded as a wimp in need of hardening up – Charles was sent to Gordonstoun, where he was bullied and miserable.

At the same time, it would be wrong to accept a caricature. This was, after all, a family famous for playing parlour games and charades, and Philip was also conspicuously engaged with his children in outdoor pursuits of various kinds, pursuits which Charles and Anne both enjoyed enough to keep up far beyond childhood.

No less inadequate is the picture of Philip as a hidebound, hang-’em-and-thrash-’em old Tory; for a man of his generation and background he had a remarkable breadth of interests and knowledge. One of his biographers, Tim Heald, uncovered figures about his private library in 1991 that are revealing: he owned 560 books on birds, 456 on religion (three of which he co-wrote), 373 on horses, 353 on the navy and ships and 203 on poetry.

In fact, philosophy and religion, alongside concern for the environment, dominated his thinking in later years, evidence of a deepening view of human existence. When Charles and Diana parted he wrote her a series of letters and it appears that far from being abusive as gossip suggested they were thoughtful, reflective and even supportive – he knew better than most, after all, what it was like to be an outsider.

An extremely active and energetic man all his life, he resented the onset of old age, giving up or winding down his activities only grudgingly and slowly. He played polo until he was 50 and even then exchanged it for carriage driving. He piloted aircraft into his sixties and only gave up driving after a car crash at the age of 97. As for his committee work and public engagements, he remained a relatively busy royal even in his eighties before finally retiring in his nineties.

And through it all, he retained and discharged with little visible fuss the role for which he has been least noted but which, in the sweep of history, was almost certainly his most important – as husband and first supporter of the monarch.

Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, born 10 June 1921, died 9 April 2021

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments