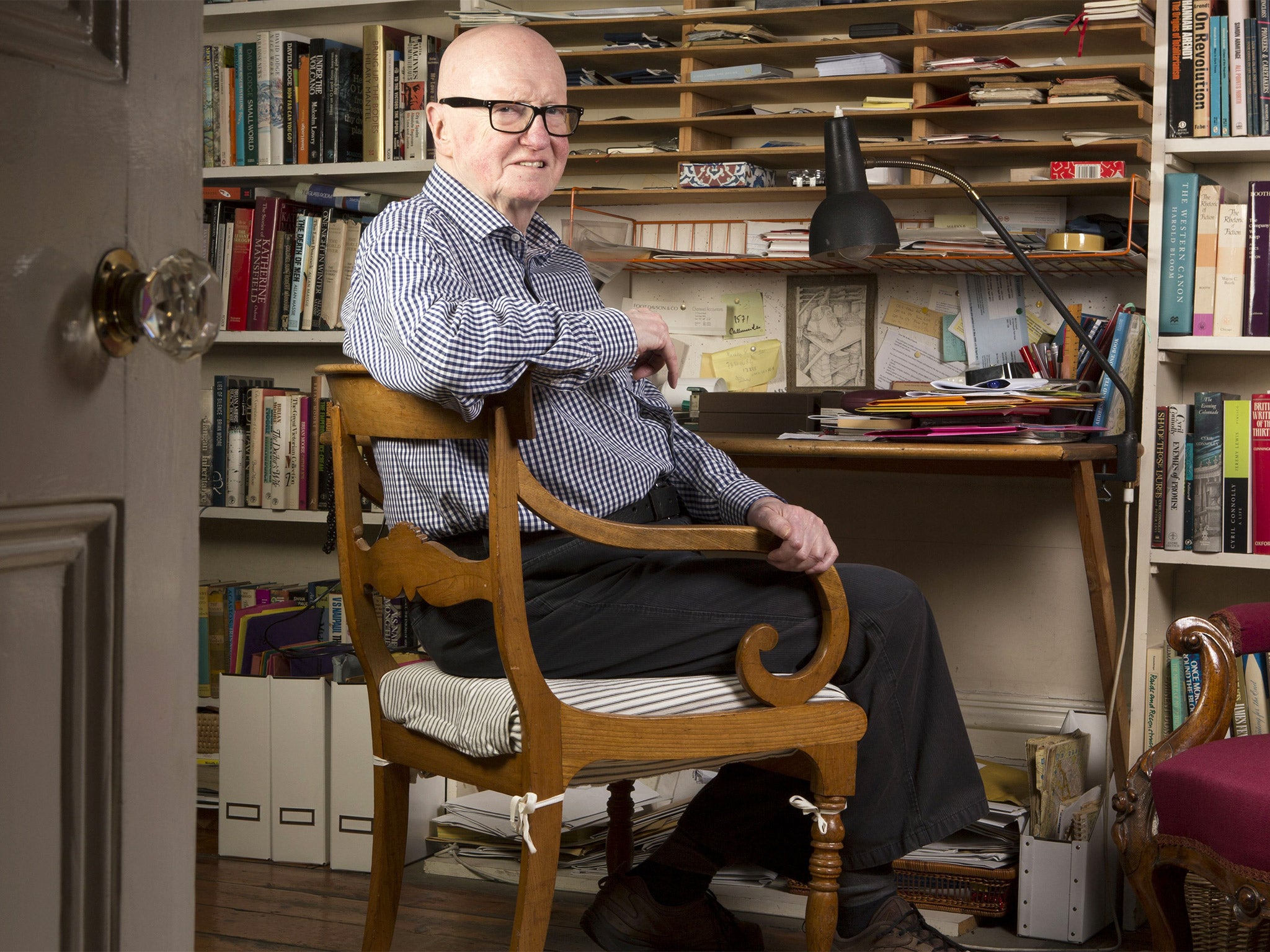

Philip French: Film critic who wrote for the Observer for more than fifty years

French won acclaim for his insightful, eloquent reviews

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The film critic Philip French's education in cinema began with a trip to “the pictures” at the age of four, accompanied by his father. It was 1937, few people had television sets to tune in to the BBC service that had begun the previous year – and the young cinemagoer was entranced by the auditorium, the commissionaire sporting a moustache and war medals, the usherette selling ice creams, chocolate and cigarettes, the parting of the curtains, the dimming of the lights and – when the Saturday matinée flickered into action – the enormous close-ups of characters and changes of location.

French was immediately addicted and, along with regular trips to the cinema, read the weekly magazine Picturegoer – and later Sight & Sound – from cover to cover, as well as dozens of books about film. The literature, music and history he absorbed from all of this combined to create one of Britain's most informed, enduring and influential critics.

He wrote for The Observer for more than 50 years, starting as part-time deputy film critic in 1962 and becoming full-time chief critic and deputy film editor 16 years later. After eloquently sharing his insights into life and the human condition as depicted in thousands of films, he retired in 2013 on turning 80, but continued to write for the paper. His last piece, on the DVD release of the 1955 Ealing Studios comedy The Ladykillers, appeared last Sunday.

Over that time, he witnessed the ups and downs of British film production and the disappearance of many cinemas. He wrote knowledgeably – sharing his own love of films – on everything from Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton silents to Hollywood Westerns, his favourite genre. He supported British directors with an independent voice, including Mike Leigh, Ken Loach, Terence Davies and Peter Greenaway, and encouraged new film-makers such as Christopher Nolan.

His all-time favourite films and directors were mostly ones from his childhood and formative years, such as La Grande Illusion (Jean Renoir, 1937), Stagecoach (John Ford, 1939), Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941), Wild Strawberries (Ingmar Bergman, 1957) and Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958). French's idol was the theatre critic Kenneth Tynan, also an Observer writer.

He attributed his own talent for making puns to suffering a stammer throughout his life – something he wrote about when The King's Speech, starring Colin Firth as George VI, was released in 2010. “Because of my impediment, I've noted and archived every stammer I've heard or seen on the stage, in films and broadcasting, read about in books or come across in any notable way in my experience of public and private life,” he explained.

One of French's favourite puns came in his first column after joining The Observer full-time, a week after his predecessor, Russell Davies, had reviewed Close Encounters of the Third Kind. French described Donald Sutherland's Italian fascist being pelted with horse manure by communist peasants in Bernardo Bertolucci's epic film 1900 as “a close encounter of the turd kind”.

French was born in Birkenhead, Cheshire, the son of John, an insurance seller, and his wife, Bessie (née Funston). His father's job meant that the family moved around. French attended Merchant Taylors' School, Crosby, Liverpool, and Bristol Grammar School, then did national service as a second lieutenant in the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry (1952-54) seconded to the Parachute Regiment in the Suez Canal zone.

On graduating in law from Exeter College, Oxford (1954-57), French won a scholarship to study journalism at Indiana University (1957-58). While there, he reviewed drama for the New Statesman and films for the London Magazine. He joined the Bristol Evening Post as a reporter (1958-59) after working in a car showroom in that city for four months.

Broadcasting beckoned and French became a producer for BBC radio's North America Service (1959-61). Switching to its domestic service, he was a talks producer (1961-67) and senior producer (1968-90). He brought his love affair with film to the arts reviews New Comment (1964-66), The Critics (1966-67), The Lively Arts (1968-69), The Arts This Week (1969-71), Arts Commentary (1972-3) and Critics' Forum (1974-90). He also wrote and presented arts documentaries.

From his days at university, where he edited the student magazine Isis and was vice-chairman of the film society, French was a libertarian and campaigner against McCarthyism, homophobic laws and censorship. He was one of only a few film critics who railed against attempts to ban Bernardo Bertolucci's Last Tango in Paris (1972).

His books included The Films of Jean-Luc Godard (1967), The Movie Moguls: An Informal History of the Hollywood Tycoons (1969), Westerns: Aspects of a Movie Genre (1973), Wild Strawberries (written with his wife, Kersti, 1995), Cult Movies (with his son Karl, 1999), Censoring the Movie Image (with Julian Petley, 2008) and I Lost It at the Movies: Reflections of a Cinephile (2011).

A member of the jury at the 1986 Cannes Film Festival, when the Palme d'Or went to The Mission, directed by Roland Joffé, French won the British Press Awards Critic of the Year title in 2009, a year after he was made an honorary life member of Bafta. In 2013, he was awarded a BFI fellowship and appointed OBE for his services to film.

French, who died of a heart attack, married Kersti Molin in 1957 while at Indiana University. She survives him, along with their children, Karl, Sean and Patrick.

ANTHONY HAYWARD

Philip Neville French, film critic and radio producer: born Birkenhead, Cheshire 28 August 1933; OBE 2013; married 1957 Kersti Molin (three sons); died London 27 October 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments