Peter Rice: Designer whose work benefited from his ability to distil complex ideas into simple images

For more than six decades, whenever his name was attached to a project, producers and production managers would relax

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For more than six decades, whenever Peter Rice’s name was attached to a project for the theatre, opera or ballet ,producers and production managers would relax, sure in the knowledge that his set designs (he usually also designed the costumes) would be distinguished and delivered with unfailing good humour on schedule and, vitally in commercial and subsidised theatre alike, on budget.

Having made his name in the 1950s when sharp, fast-moving intimate revue still flourished before Beyond the Fringe sounded its death-knell alongside undemanding light comedy on Shaftesbury Avenue, Rice became stamped primarily as a designer of choice in the Cecil Beaton/Oliver Messel painterly tradition of decorative elegance. His eye for colour – stimulating in the pallid grey of post-war austerity – and technical ingenuity suited him to the demands of quick-change revue and to frivols from established comedy writers such as Hugh and Margaret Williams or Ray Cooney; however much of his opera work and some remarkable designs for off-West End venues such as Greenwich Theatre in the 1970s and ’80s saw some very different aspects of a remarkably versatile talent.

Rice was a child of the Raj, born in Simla and then educated in Surrey (St Dunstan’s, Reigate) where his precocious passion for the decorative arts flourished, leading him to train as a painter at the Royal College of Art. His first professional project was at the adventurous little Watergate Theatre on the intriguingly titled (but, according to Rice, disappointingly tame) play Sex and Seraphim (1951).

Opera involved him from early in his career, beginning with an elegant and jewel-hued take on a favourite Mozart piece, Il Seraglio, at Sadler’s Wells (1952). An early ballet excursion saw him collaborate with Sir Frederick Ashton on Romeo and Juliet (1955) for the Royal Danish Ballet.

An Old Vic season (1956) for which Rice designed three Shakespeare plays was distinguished by Michael Benthall’s lucid production of The Winter’s Tale, graced by a fine cast including Wendy Hiller’s unusually spirited Hermione in Rice’s neo-classical set against a background of atmospheric skyscapes. West End work included successful ventures in revue – Living for Pleasure (Garrick, 1958) with Dora Bryan in drollest form and The Lord Chamberlain Regrets (Saville, 1961) featuring some fine work from Millicent Martin – while in the straight-play field his haunting, wintry chateau for Françoise Sagan’s offbeat family drama Castle in Sweden (Piccadilly, 1962) was among his best work of this time.

This rich period ran in parallel with the early years of Rice’s long and happy marriage to designer Pat Albeck, then just beginning her association with the National Trust. Her eye for colour matched that of her husband – the kitchen of their tall, terraced Hammersmith house near the river was crowded with bright Clarice Cliff pottery and paintings by another local resident, Mary Fedden.

Under Sir John Clements’ leadership at the Chichester Festival Theatre Rice proved a master of that tricky hexagonal stage, graveyard of not a few designers. A landmark season was 1966, when he came up with designs as varied as the warm, bucolic countryside for Phillpott’s The Farmer’s Wife, a superbly adaptable solution to the interior and exterior demands of Shaw’s Heartbreak House and the riotous technicolour romp of An Italian Straw Hat.

South London’s Greenwich Theatre proved a congenial home for Rice whose many production throughout the 1970s and ’80s ranged from a breathtaking recreation of Manet’s “Dejeuner sur L’Herbe” for David Pownall’s An Audience Called Edouard (1979) with Jeremy Irons centre and Susan Hampshire nude on the right, and a revelatory scrutiny of Pinter’s Betrayal (1984) in its first London revival; Rice took a radically pared-down approach, using only some key pieces of furniture set against an inky void for the play’s various locations.

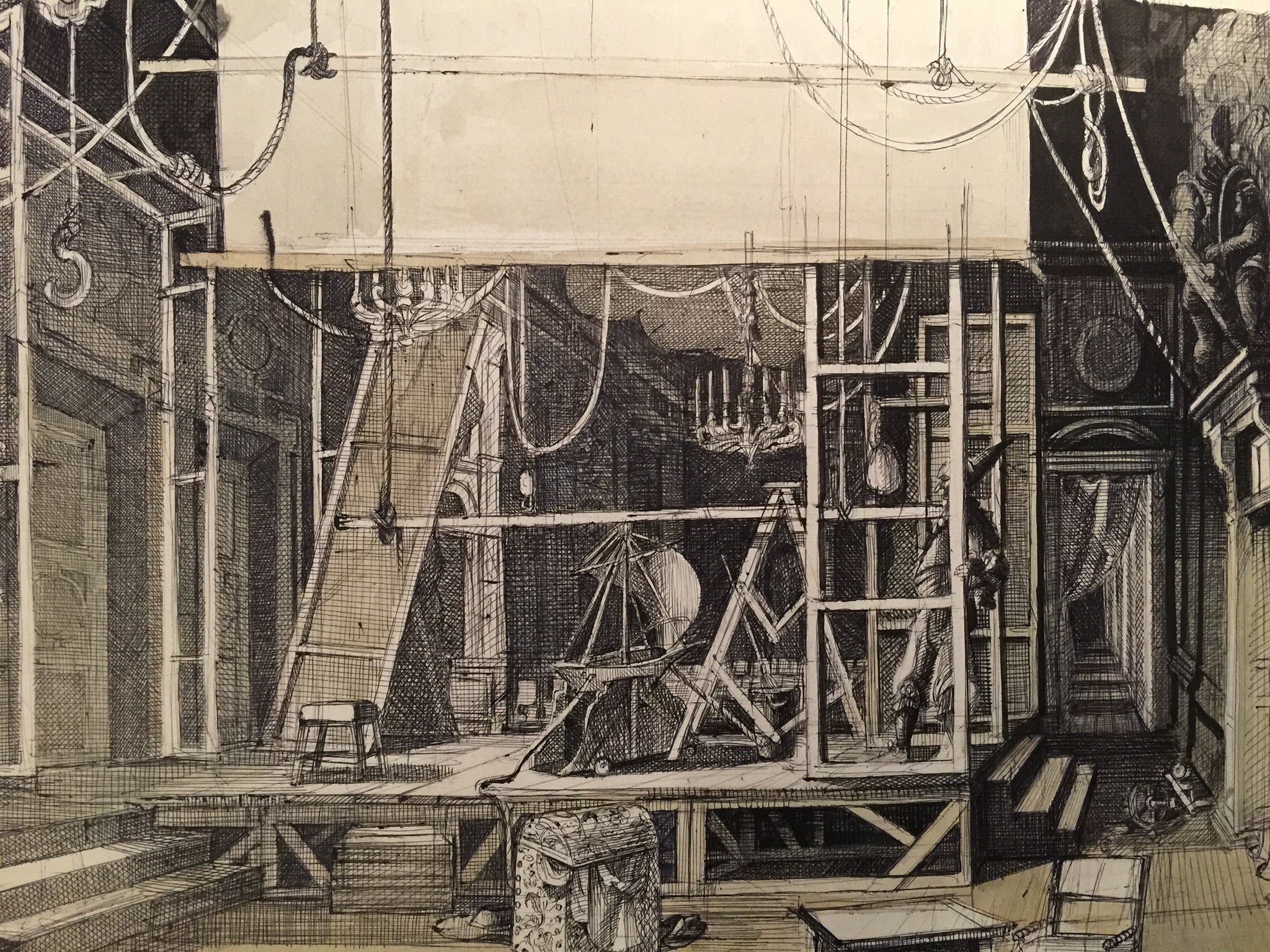

A rewarding link with Scottish Opera from the 1960s gave him a choice run of productions, often for Anthony Besch or Peter Ebert – Faust, Falstaff, La Boheme and, most notably, the Tosca (1980) with Besch which remained in the Company’s repertoire for three decades. Intending to relocate to the era of Napoleon’s occupation of Italy, after viewing Rossellini’s Rome, Open City, Rice and Besch changed their setting to Mussolini’s Rome. Crystallising his belief that “the designer is the eyes of the production and the director the brain” and also his fondness for complex ideas distilled into simple images, Rice came up with three memorable sets, the final act on the ramparts of the Castel St’Angelo dominated by a vast statue shrouded in scaffolding being particularly striking.

Continuing to work with undimmed enthusiasm into his eighties, Rice found a happy association with Holland Park Opera, an organisation which he much admired. Always encouraging to younger talent, Rice was proud to see some of his assistants strike out on successful solo careers – they included Paul Farnsworth and Lez Brotherston (whose work for Sir Matthew Bourne’s version of Swan Lake he thought very fine). He also had happy times when refurbishing two favourite theatres, the Vaudeville in the Strand in 1970 Aberdeen’s His Majesty’s.

Resettled in a charming Norfolk village, Rice worked for over a year on a large mural designed for the Stoke factory of his ceramicist daughter-in-law Emma Bridgewater. His son Matthew, remembering Rice’s stories of working on the interior of a house in the Bahamas, suggested a mural incorporating Stoke landmarks such as the Spode and Wedgwood factories amid elements of Bahamian history. The design was an exuberant explosion of colour; it will remain a life-enhancing reminder of a delightful man and his talent.

Peter Anthony Morrish Rice, stage designer: born 13 September 1928; married 1954 Patricia Albeck (one son); died 24 December 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments