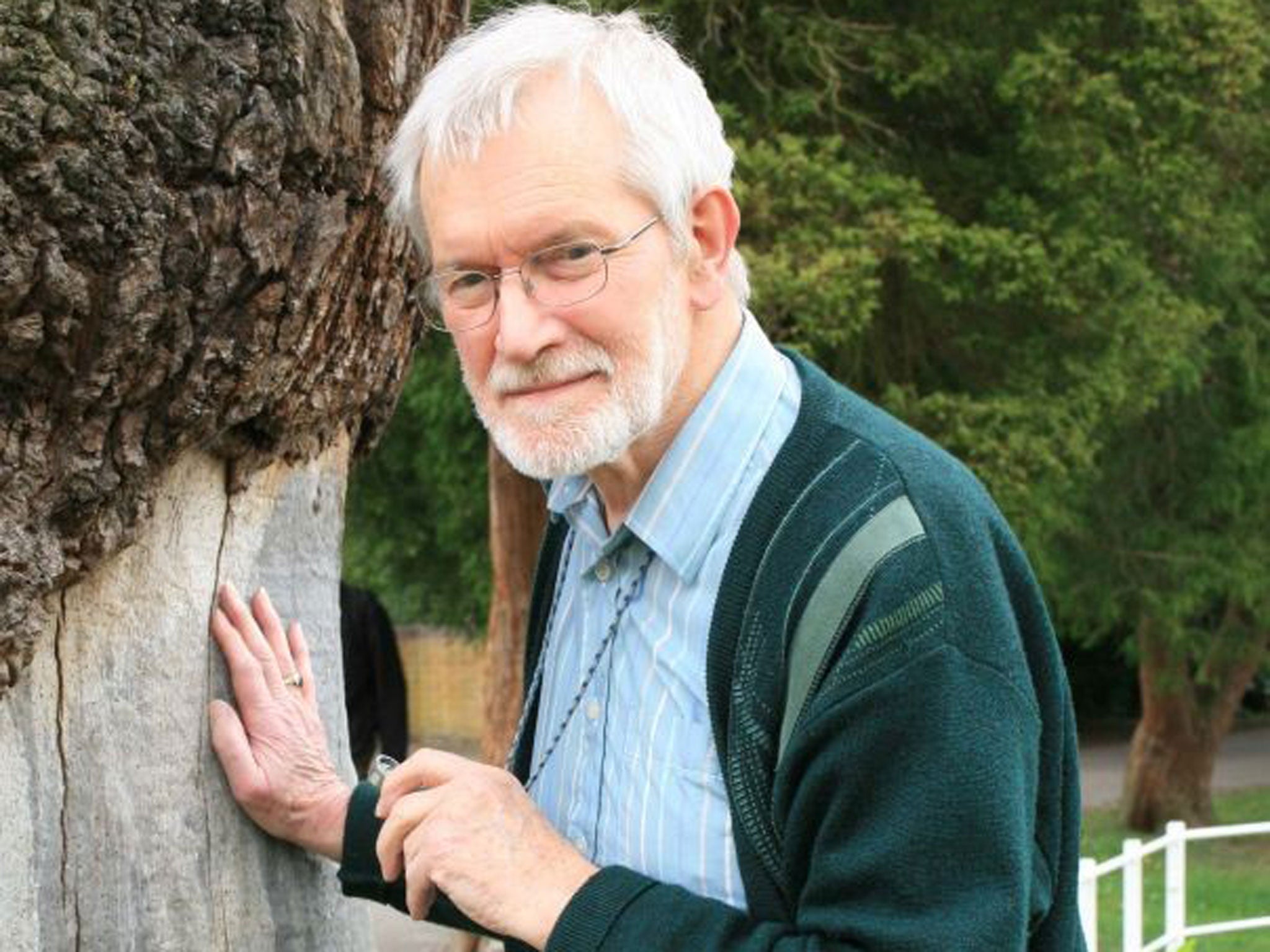

Peter James: Lichenologist who was one of the first to establish the study of these primitive plants as a scientific speciality

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.To anyone interested in wild plants the name of Peter James and the study of lichens are virtually synonymous. When he began his career, very few botanists specialised in lichens, primitive plants which combine fungi with algae. Today lichenology is a well-established scientific discipline in Britain, with, its own Society, journal, regular field meetings and a notably dedicated band of followers.

Despite their difficulty lichens are well recorded – Britain has as rich a lichen flora as anywhere in Europe – and the importance of lichens as environmental indicators, especially for atmospheric pollution, is well known. Many such advances can be traced back to when James started work in the Natural History Museum in 1955.

Lichens were his hobby as well as his job. James spanned the different worlds of amateur and professional lichenology and was never happier than on an excursion with fellow enthusiasts. It is said that there was nowhere he had not been and no specimen he could not identify. He had a wizard's eye for finding obscure or minute species that others had missed. Indeed James identified so many parcels of specimens that at times he felt he was becoming a machine for naming lichens.

But along with a taxonomist's eye and a phenomenal memory he was unfailingly patient and generous with his time, and a gifted teacher. All the great lichenologists of that generation, such as Oliver Gilbert, David Hawksworth, Mark Seaward and Brian Fox, acknowledge the his central role in encouraging and facilitating the growing science of lichenology.

Peter (never "Pete") James was tall and slim, with a courteous and slightly formal demeanour. In later life he grew a neatly cropped beard. A lifelong bachelor, he was firmly set in his likes and dislikes. He was a good cook and served immaculately presented dinners in his flat at Baron's Court lined with books and classical music records. He loved cacti, though most of his collection of 600 species had to be stored at his sister's house in the Midlands. On the other hand he never learned to drive or to work a computer, and refused to use a mobile phone. Most of his voluminous correspondence was handwritten.

In the field he was a fearless explorer of the wet, rocky places where many lichens are found. A friend in Tasmania found him an inspiration but hopelessly clumsy in the bush. "You had to watch him near precipices. On one occasion he ignored my warnings and was hammering fiercely at a rock outcrop standing in front of a wombat's burrow. Of course the wombat duly returned – a 10-gallon keg's worth of muscle travelling at speed – and with an 'Oh, my gosh,' Peter, hammer, chisel and specimens all parted company."

Peter James grew up in Sutton, then a rural suburb of Birmingham, the son of a local headmaster. Keen on wildlife from boyhood, he read botany at Liverpool University, a course then known for its thorough grounding in the "lower plants". Emerging with a first class degree he enrolled for a PhD, choosing as his subject the succession of lichens on twigs, having been inspired by the lush lichens he saw on a field trip to Wales.

For a variety of reasons he never completed his doctorate but took up a summer vacation studentship at the Natural History Museum. There he made his mark; when a full-time post for a lichen specialist was advertised he was selected and started work the next day. He remained at the Museum until his retirement in 1990, latterly as Deputy Keeper of botany.

James was one of the founders of the British Lichen Society in 1958 and became the first editor of its prestigious journal, The Lichenologist, a role he continued in until 1977. He also played a key part in the development of Britain's published lichen flora. He was a leading light on the Society's field trips which ranged over the whole of Britain and amounted to a systematic exploration of our lichens.

Many new species were discovered and a camaraderie was forged, camping out in remote, mountainous places and islands – a sport described as "adventure lichenology" by Oliver Gilbert. Among the places James surveyed more than once was Stonehenge, for which he produced separate species lists for each of the 82 stones that make up the monument – including the bright-yellow lichen Candalariella which flourished wherever English Heritage had tried to remove paint graffiti.

His interests extended overseas to temperate South America as well as Australia, New Zealand and the Atlantic islands. He was a founder member, acting treasurer and first president of the International Association for Lichenology and co-ordinated its first field meeting in the Austrian Alps in 1971. Among other activities of a busy professional life were botanical congresses, service to various bodies from the Field Studies Council to British Petroleum, and acting as external examiner for doctorates at home and overseas. After his retirement he became a founder member of the conservation charity Plantlife, which he served as vice-chairman.

In 1992 James was awarded the Acharius Medal for lifetime achievements in lichenology. The citation described him as "a gentleman of lichenology" – which sums him up perfectly. µ PETER MARREN

Peter Wilfrid James, botanist and lichenologist: born Sutton Coldfield 28 April 1930; died Birmingham 13 February 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments